painting, plein-air, oil-paint, impasto

#

painting

#

countryside

#

impressionism

#

plein-air

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

flower

#

house

#

impressionist landscape

#

nature

#

oil painting

#

impasto

#

plant

#

building

Copyright: Public domain

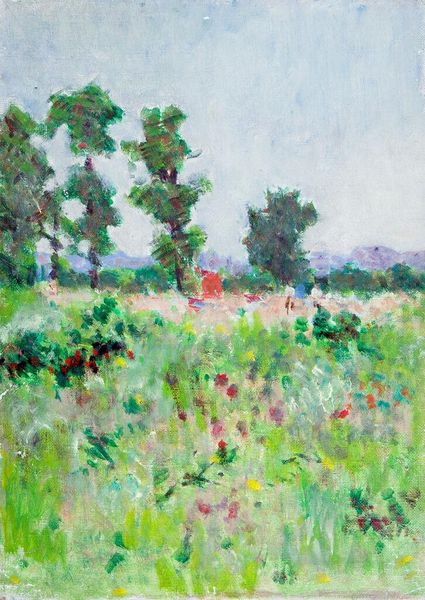

Curator: Well, hello there. We’re looking at Konstantin Korovin’s "Hollyhocks in the Saratov region," created in 1889. Korovin, a master of Russian Impressionism, rendered this plein-air painting with oil on canvas. Editor: It’s… blurry, almost. Like a hazy memory of a summer afternoon. The colours just sort of bleed into each other. It feels very dreamlike, doesn’t it? And the textures are surprisingly rich for such a wispy image. Curator: Exactly. Korovin was experimenting with capturing fleeting moments and atmospheric conditions. The "blurriness," as you call it, is a hallmark of Impressionism—an interest in the subjective experience of light and colour. The visible brushstrokes add a sense of immediacy. We know this painting was composed *en plein air*, giving it an extra sense of observation of a direct and unedited vista of Russian life. Editor: It also reminds me a bit of early photography, when lenses weren’t quite so sharp, and everything had a gentle, soft focus. It also makes me think of how memory works: highlights are prominent while details recede in fuzziness and incompleteness. Is it fair to say there are sociopolitical connotations to showing flowers around a Russian building at that time? Curator: It is true that his art stood apart during a period when Russian art often leaned towards social realism, depicting the lives of the peasantry with a strong, often didactic, narrative. Korovin, on the other hand, celebrated the beauty of everyday life, perhaps offering an escape from the harsh realities. In the 1880s, Impressionism became a silent protest in favor of individuality. The hollyhocks almost form a veil in front of the house, softening its presence. Editor: Yeah, that makes sense. They’re not just decoration, they’re… a mood. A filter. Well, I find this type of history super interesting. They remind me of my own time in Russia…it may sound very silly, but the painting does. I had quite an enchanted time myself there. Curator: And in turn, it reminds us of the ways in which aesthetic preferences themselves carry cultural and political weight. Ultimately, Korovin gives us a piece to remember life’s daily impressions and subtleties. Editor: So, here's to daily impressions, to enchanted memories, and a damn good blurry painting.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.