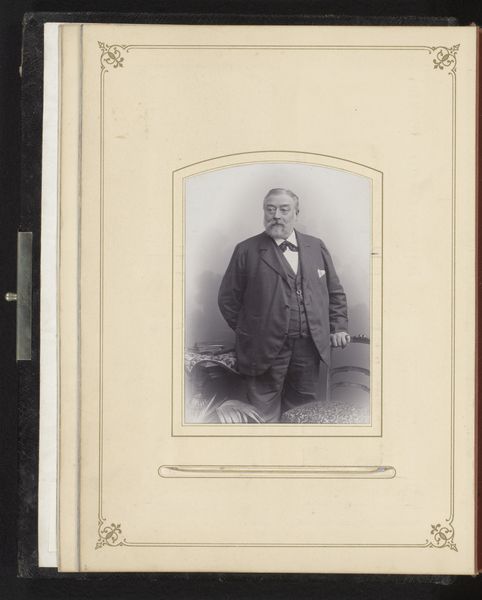

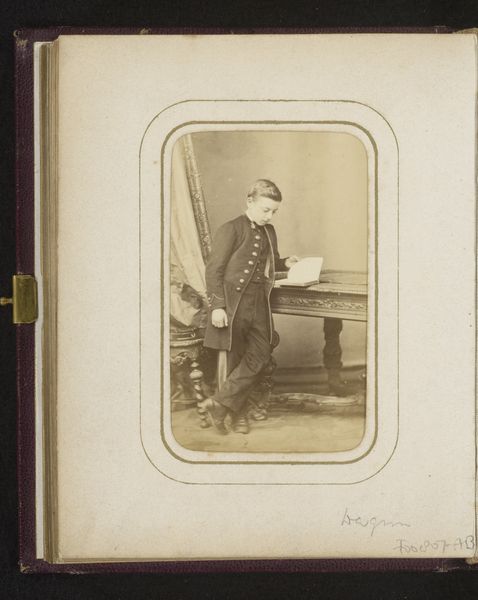

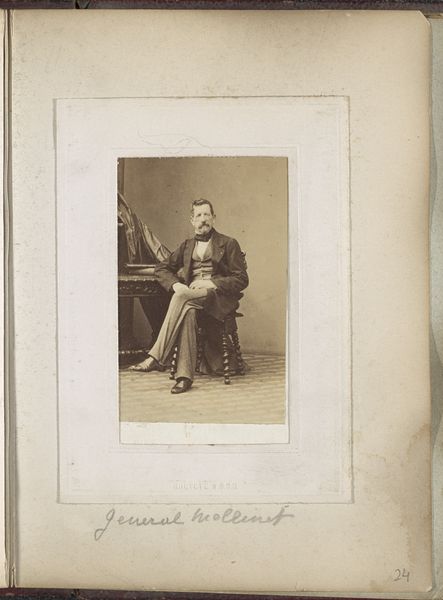

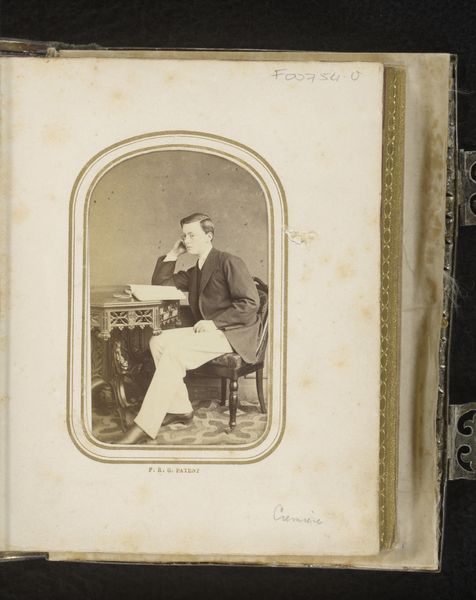

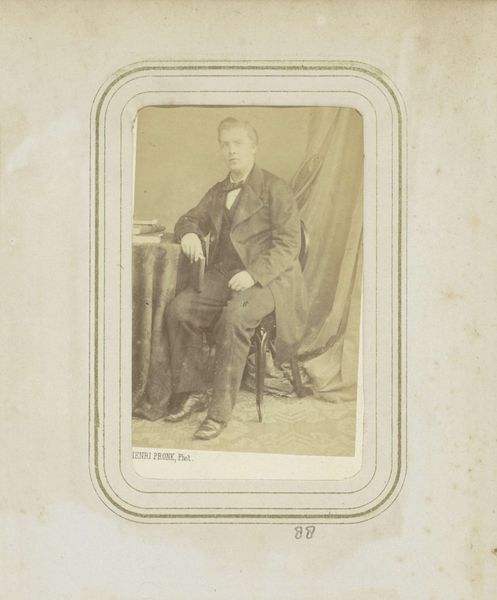

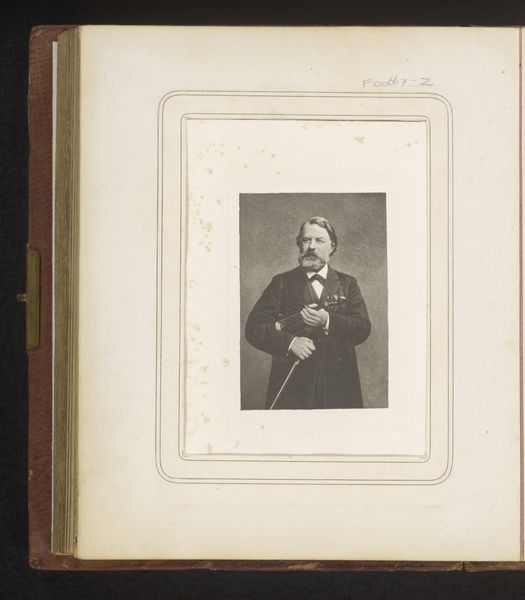

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

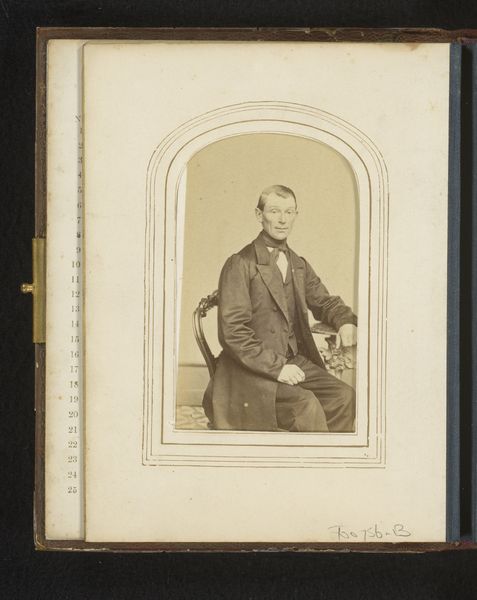

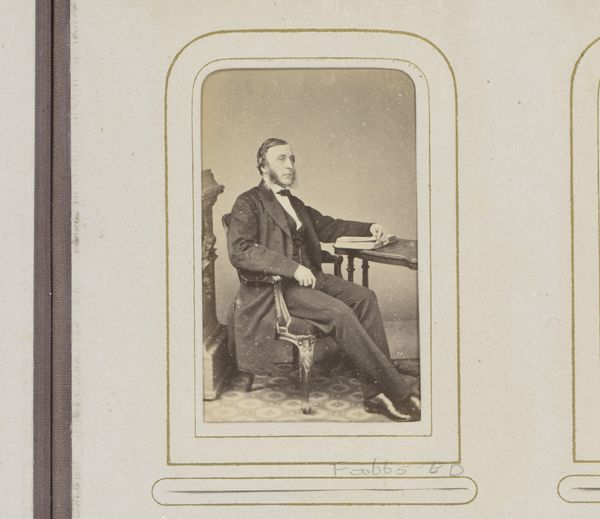

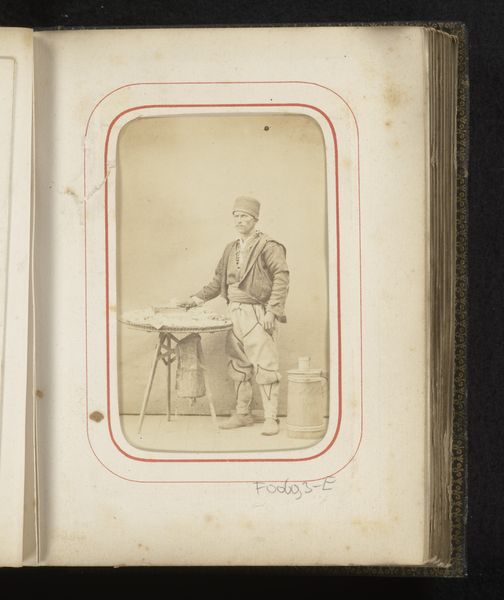

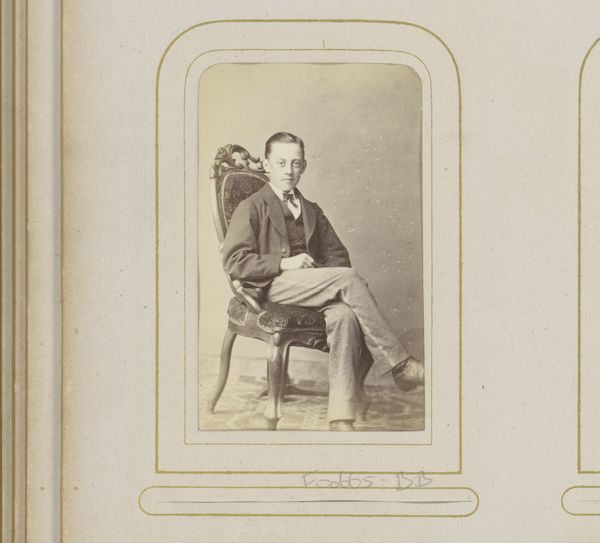

portrait

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 137 mm, width 95 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

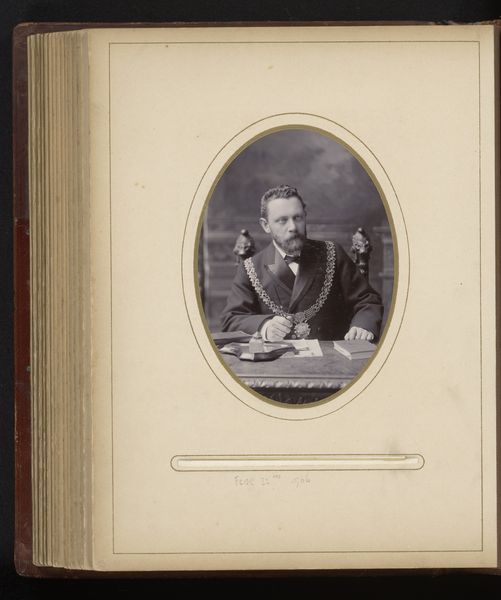

Editor: Here we have "Portret van J. Hastings," a gelatin-silver print from around 1870-1900 by T.C. Turner. He looks so formal, with all those medals. What strikes you about this piece? Curator: What I see is a very carefully constructed representation of power and belonging. This image operates within specific social and political landscapes. Consider the sitter's masonic apron. It invites questions about the role of fraternal organizations in solidifying power structures during this era. How does the image participate in constructing a certain kind of masculinity? Editor: Masculinity? I thought it just showed a guy. What clues tell you that? Curator: Think about it: the stiff posture, the medals denoting service, the carefully cultivated beard, the gaze directed just past the viewer. These aren't just neutral details; they're signals. It also makes me consider how photography itself was developing as a tool for social documentation and control, solidifying these power structures for posterity. Who was included in this visual history, and who was excluded? Editor: So it's not just a picture, it's a statement about belonging and influence. Does the photograph's medium contribute to this, and what about his social status as it relates to that era? Curator: Absolutely. Photography at the time was becoming increasingly accessible but still carried a certain weight of authority. By commissioning a portrait like this, Hastings and Turner were actively participating in a system that valued certain kinds of individuals and experiences over others. I encourage us to reflect on how visual representation can be a tool for both reinforcing and challenging existing social orders, even today. Editor: That's given me so much more to think about, thank you. I won’t look at portraits the same way. Curator: That's the goal. It's all about expanding our understanding of whose stories are told and how, and whose are not.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.