Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

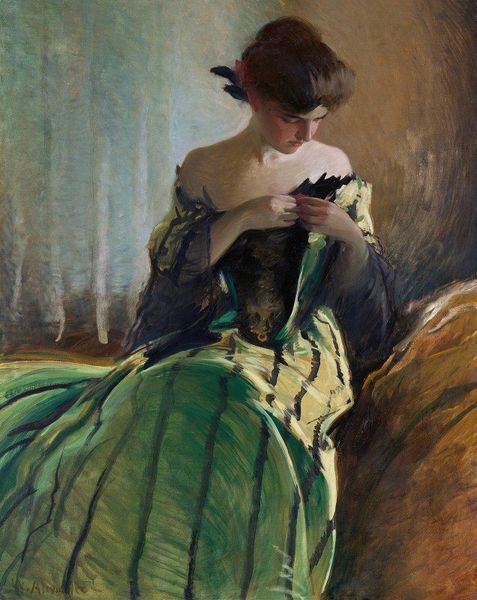

Curator: We're looking at "La Femme Et L’amour," painted by Alfred Stevens in 1885. It’s an oil painting depicting a woman reading, seemingly undisturbed, with a cherubic figure observing from a nearby balcony. Editor: My first impression is how the dress itself seems to possess its own sculptural quality. The fabric drapes and pools, it's rendered almost as a character, all stiffened silk and applied decoration. How much would such a dress cost? And how long did it take to make? Curator: It certainly is arresting. This painting belongs to a lineage of images where the symbols of domestic life are imbued with layered meanings. The cupid, for example, isn’t simply a decorative element, it is meant to provoke a conversation on love and the human condition, specifically, woman’s interior life, love in the gilded cage, in this historical moment. Editor: The labor involved in producing that very distinct late 19th-century ideal of femininity interests me the most here. What kind of industries had to flourish for this scene to be recorded in paint? I imagine several types of lace makers, dressmakers, pattern-cutters... each with unique skill sets. What can the consumption patterns tell us about the economy of the time? Curator: Precisely. The cherub feels like both a commentary and perhaps a wink; it represents, among other things, the constricting societal expectations that govern a woman's desires and prospects within this bourgeois milieu. She's at leisure but under constant watch by Love itself! Editor: Absolutely. The painting then, becomes a document, however gilded, of commodity culture. Oil paint to depict silk becomes yet another layer. It's not just an aesthetic rendering but an echo of other, often hidden, productive realities. Even the canvas upon which the paint rests has stories to tell. Curator: It really showcases how these carefully arranged scenes speak volumes, both through their presence and through the absences they deliberately conceal. Editor: Agreed. Seeing this work allows for a discussion on the economics of romance, doesn’t it? Curator: Indeed, a powerful visual allegory, both captivating and unnerving. Editor: Right. And for me it also provokes further inquiries into production of those signifiers themselves.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.