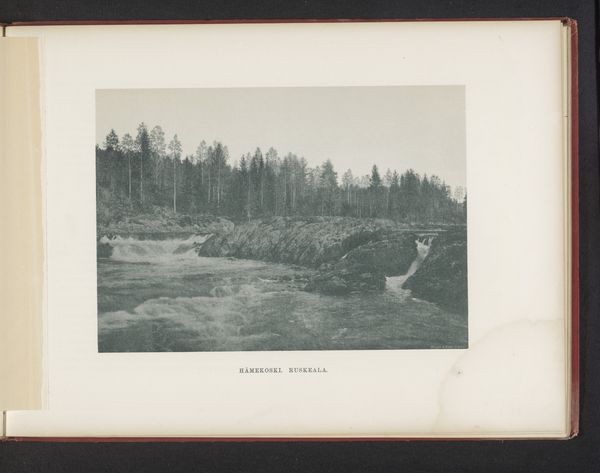

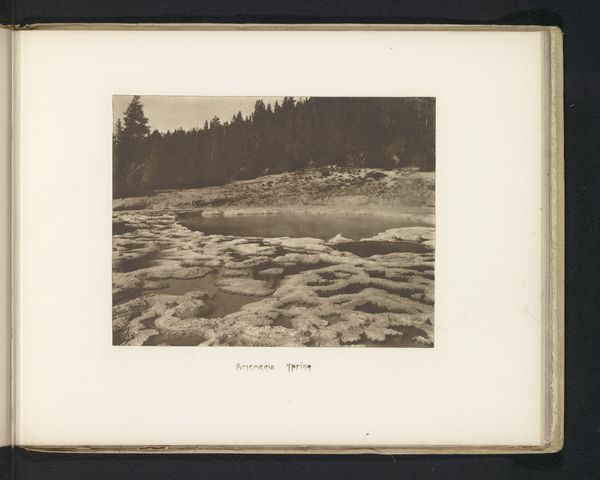

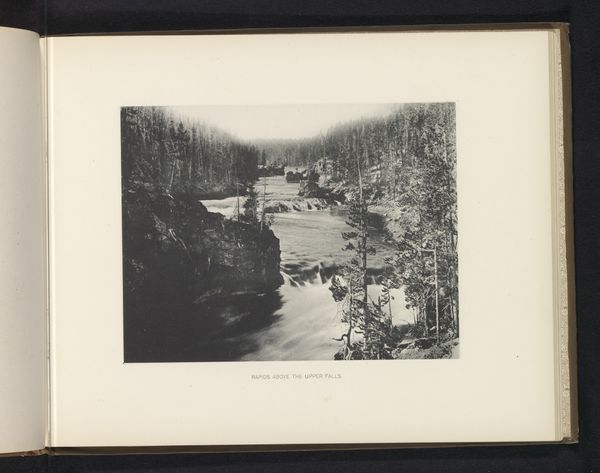

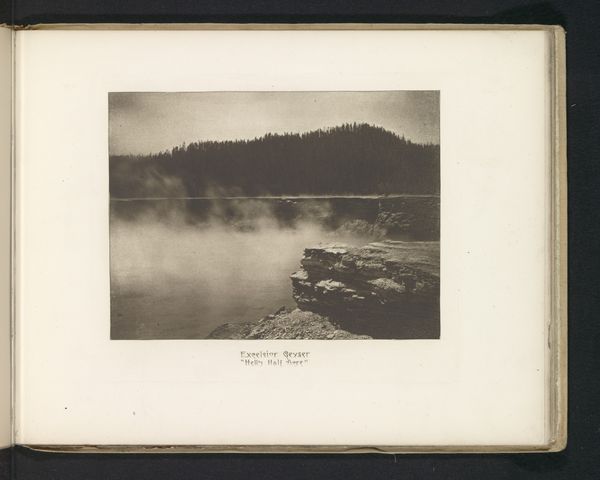

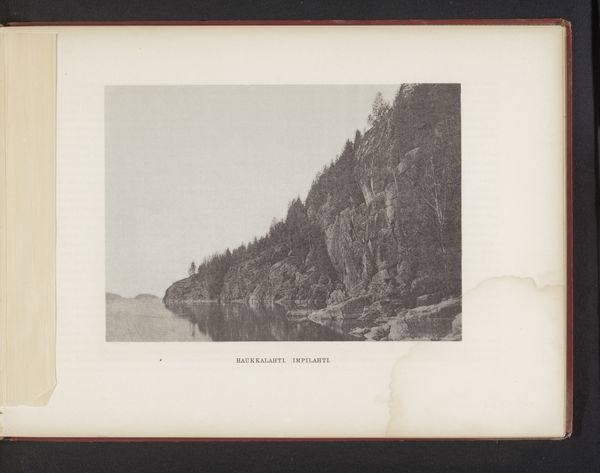

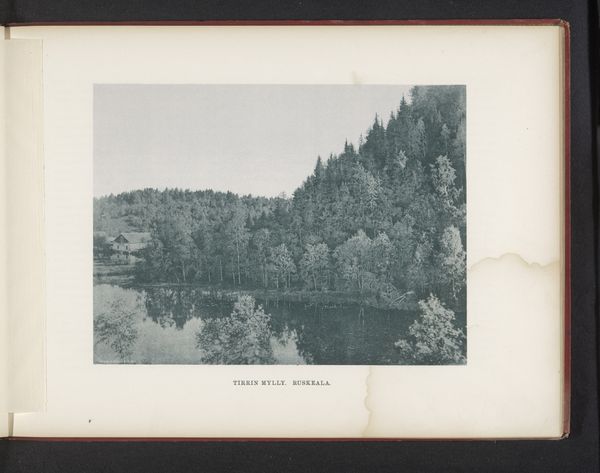

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

pictorialism

#

landscape

#

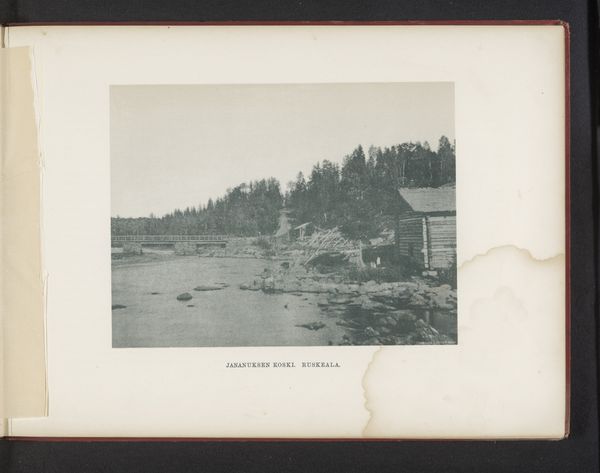

river

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 164 mm, width 214 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

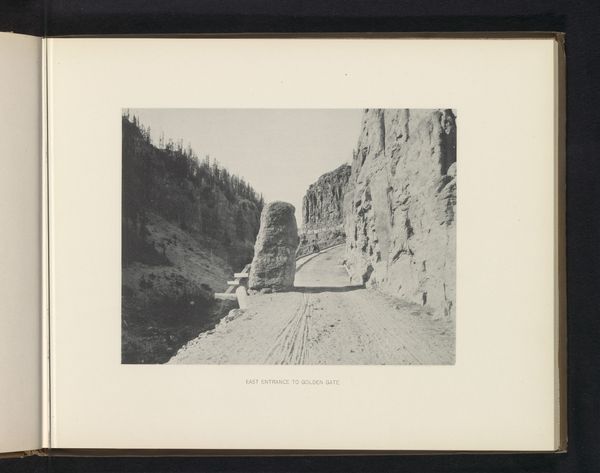

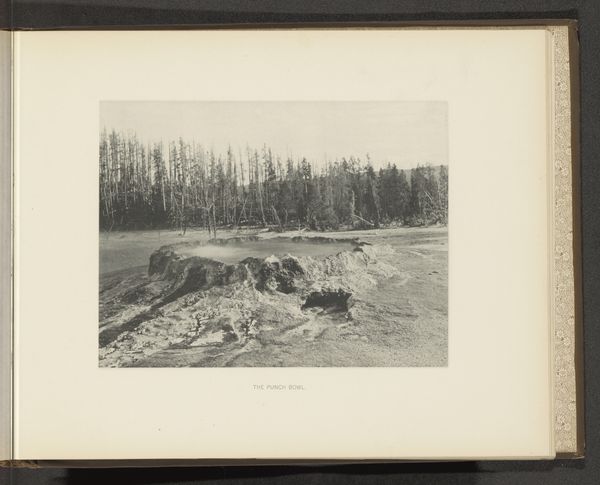

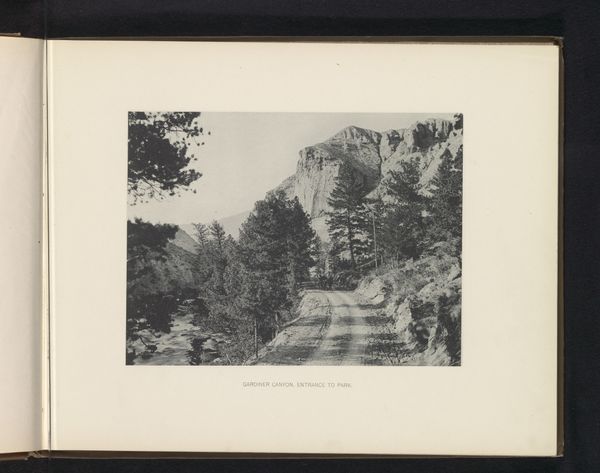

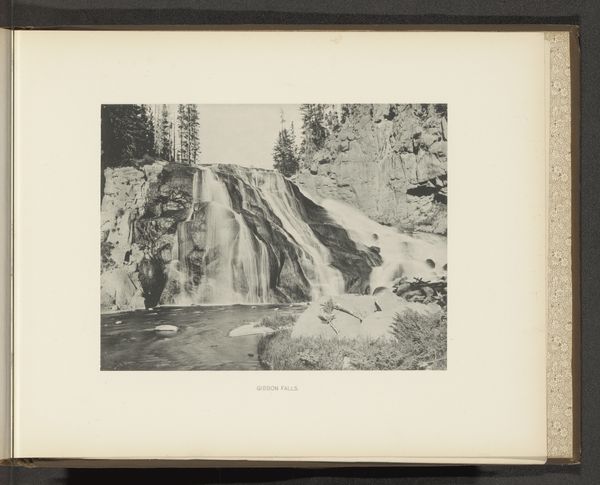

Curator: Frank Jay Haynes captured this evocative landscape titled "Eagle's Nest Rock, Gardiner Canyon" sometime before 1891. It's a gelatin silver print. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is its serene stillness despite depicting a rushing river. The way the water blurs against the sharply defined rocks creates an intriguing textural contrast. Curator: That juxtaposition is very deliberate, and quite common for its time. Landscape photography was a booming industry, fueling westward expansion narratives. The commodification of nature was really underway, packaged neatly as sublime scenes. Editor: Right, it makes you wonder about accessibility and consumption of these landscapes. This image flattens the rugged terrain of the American West into a manageable, almost picturesque view suitable for a middle-class parlor. I see these as instruments of political messaging. Curator: Exactly! The silver gelatin printing process was central to this popularization. Think about the accessibility and affordability this technique enabled. Before, more laborious print methods made mass distribution difficult. Haynes' process made it possible. Editor: And speaking of labor, let’s think about how labor is represented or erased within the picture frame. A gelatin silver print itself requires many production phases, many steps taken to get the "final image", don't you think? Curator: You're hitting the critical question about these romanticized images of untouched nature. Whose labor, and what ecological consequences, made them possible? Railroad expansion enabled the tourism that then sustained Haynes' practice. It’s an economy of resource extraction and environmental transformation. Editor: Absolutely, which means there’s more to this image than just surface-level beauty. Looking at it today forces us to reconcile its visual appeal with its place in a larger web of political, economical, and material history. Curator: It prompts questions about what is gained—and what is lost—in transforming landscapes into aesthetic objects, ready for circulation and consumption. Editor: A stark reminder that the beauty we perceive has tangible roots in labor and our troubled engagement with natural resources.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.