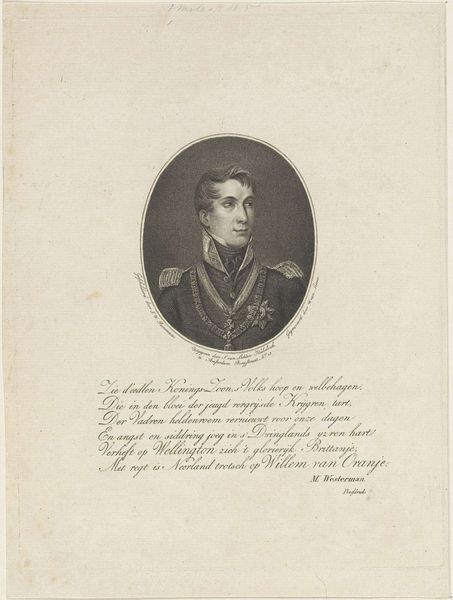

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

pencil drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 236 mm, width 182 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

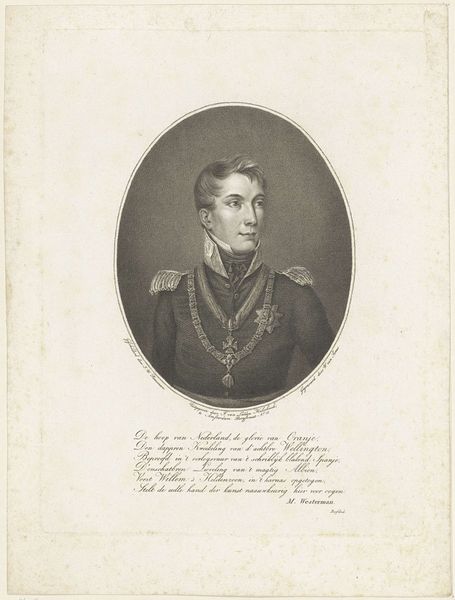

Curator: Before us hangs a print dating from between 1813 and 1851, titled "Portret van Willem I Frederik, koning der Nederlanden," which, translated, is "Portrait of William I Frederick, King of the Netherlands." This engraving can be found right here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The King looks...serious. Regal, naturally. It has a very buttoned-up formality, that circular frame, the crisp uniform. You wouldn't want to spill ink on it! Curator: Precisely. These depictions played a crucial role. Note the style aligning with Neoclassicism, it's very typical in how it elevates its subject to a figure of near mythical status during a period when national identity was being asserted through imagery and history. Editor: That circle is doing heavy lifting. It’s kind of a symbolic spotlight, a “History Is Watching You” kind of gaze. And it works, you know? Makes him loom, even though it’s just lines on paper. I do wish the typeface at the bottom was better integrated with the visual aesthetic. It makes the entire composition feel weighed down. Curator: Agreed. Yet that engraving, despite the clunky typeface, served as propaganda. Images like this circulated widely, bolstering the image of the monarch as stability, leadership personified at a time of societal reconstruction after years of war. Editor: Which is a very…official job for a piece of art. I guess back then there were no digital means. Curator: And that’s important! Without mass photography, printed portraiture allowed those who were otherwise unable to see a king access to their nation’s ruler. It creates familiarity with their ruler and reinforces the status quo. Editor: Makes you wonder what today’s engravings might look like, right? I see an older gentleman, frozen for eternity on a glossy piece of paper. An eternal statement in leadership that, in its essence, transcends epochs and reigns. Curator: Exactly. It allows one to think deeply about the very public life of art!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.