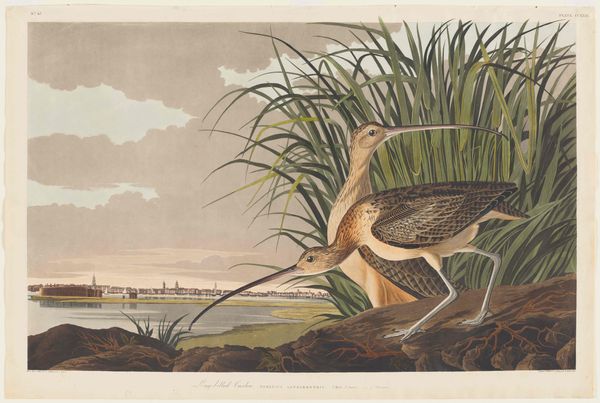

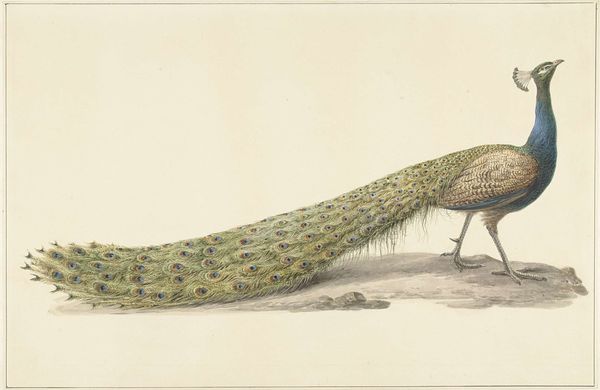

drawing, print, watercolor

#

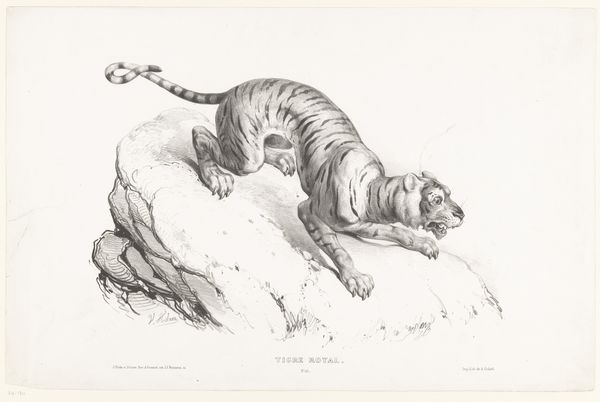

drawing

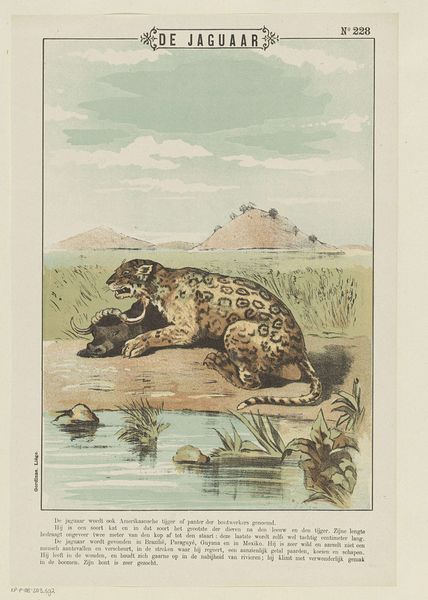

# print

#

landscape

#

botanical illustration

#

watercolor

#

botanical drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

botanical art

#

watercolor

#

realism

Dimensions: 16 x 16 1/2 in. (40.64 x 41.91 cm) (image)

Copyright: Public Domain

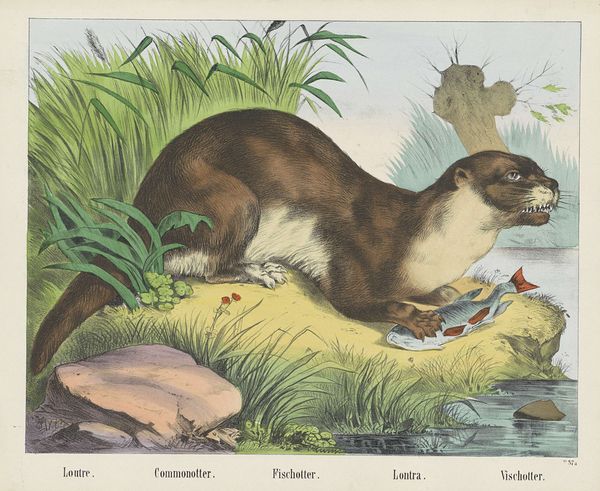

Editor: So this piece, "Leopard Spermophile," dating from the late 1840s, and currently at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, is really intriguing. The detail is amazing, almost like a photograph, but it’s a watercolor and print. What catches your eye when you look at it? Curator: I'm struck by its contribution to a specific historical narrative, one deeply embedded in both scientific exploration and colonial expansion. Consider the context: during this period, meticulous depictions of the natural world, such as this one, served as vital documentation for scientific study and categorization. It represents a quest for knowledge but simultaneously fueled the ideology of domination over the natural world, and over the lands they inhabited, since these spermophiles are, of course, not just "art". Editor: That's a fascinating point. It's easy to see them as just cute critters, but thinking about the era, it's clearly much more loaded. Do you see that reflected in the way the piece is composed, perhaps? Curator: Precisely! The composition is not accidental. Notice how the animals are carefully placed within the landscape, presenting them as specimens within a controlled environment. The backdrop, a vast, undefined territory, underscores the potential for surveying, claiming, and ultimately, exploiting the land and its resources. The precision in rendering the spermophile normalizes a specific worldview where observation equals power. Editor: So, even a seemingly innocuous image of squirrels can reveal layers of meaning related to colonialism and control? Curator: Absolutely. It serves as a reminder that art, especially within a historical framework, actively participates in constructing our understanding and relationship with the world around us, including reinforcing certain power structures. Editor: Wow, I never would have thought of it that way. This really makes me think differently about the art of this period! Thanks! Curator: My pleasure. Analyzing these visual texts opens avenues for questioning assumptions and seeing art as both reflective and formative of culture.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Late in life, naturalist John James Audubon made a final expedition to the western plains in search of four-footed mammals. These striped ground squirrels would be tempting prey for many birds, especially hawks and owls. After the squirrels had left, burrowing owls might take over their underground dens.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.