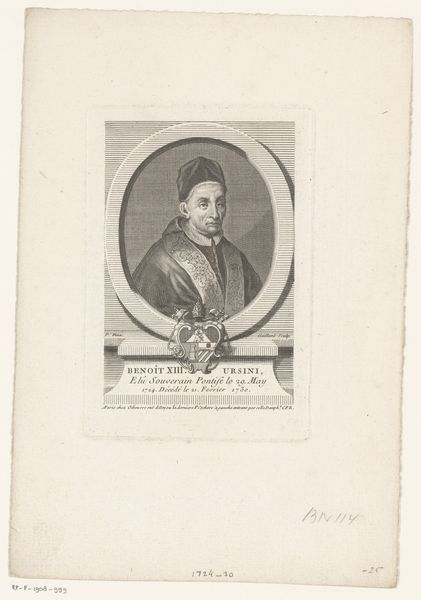

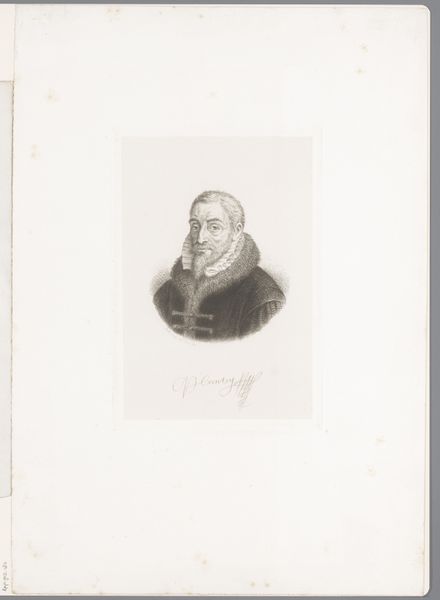

Fotoreproductie van (vermoedelijk) een prent van Willem I, prins van Oranje c. 1860 - 1880

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 69 mm, width 54 mm, height 106 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here at the Rijksmuseum we have this "Photoreproduction of (Presumably) a Print of William I, Prince of Orange." It's estimated to have been created between 1860 and 1880 using a gelatin-silver print technique. Editor: It has such an intriguing melancholy, doesn't it? The aged paper and muted colour palette evoke a tangible sense of history, a stark portrait hinting at the burdens of leadership. Curator: The gelatin-silver process would have been relatively new at the time, signifying a shift in how images were reproduced and circulated. The choice of this technique speaks to the accessibility and dissemination of historical figures during the late 19th century. It turns history into a commodity. Editor: Exactly. The ability to mass-produce images of powerful men like William of Orange speaks to the burgeoning culture of celebrity and nationalism. What role does it play in shaping Dutch identity, promoting a certain historical narrative during the time? Who consumes these images, and to what end? Curator: Those are crucial points. Think about the layers of reproduction—a photograph of a print—each stage involves different forms of labor. We can consider this from the perspective of both the photographer and the printing workshop involved in production, right down to the sourcing of materials like the paper itself, its weave. Editor: The reproduction itself begs the question: Who controls the image, the narrative? How does this seemingly straightforward portrait reflect power dynamics and contemporary struggles around historical memory, nationhood, and even colonization, thinking about the larger social context of the Netherlands during this time? Curator: Absolutely. The image has shifted in its cultural and social role across time, yet the enduring material—the photographic paper—acts as a through-line to its making, a silent testament to labour and shifting reproduction methods. Editor: Indeed. An artwork’s historical influence and social resonance becomes more interesting than the artwork itself. It forces us to ask crucial questions about history, power, and identity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.