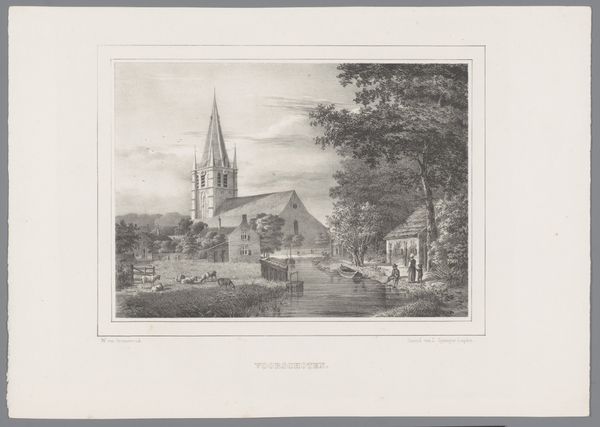

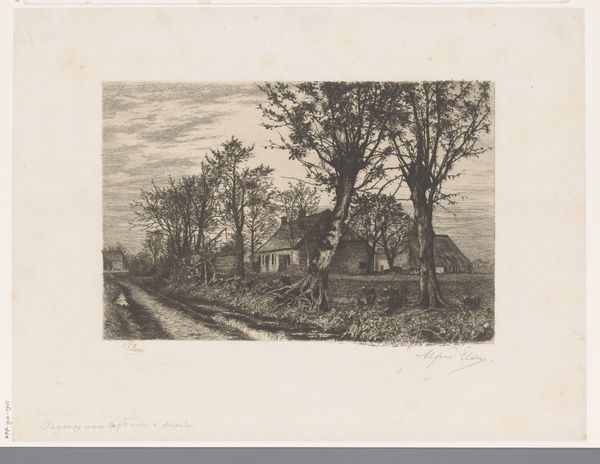

print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

cityscape

#

realism

Dimensions: height 270 mm, width 330 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

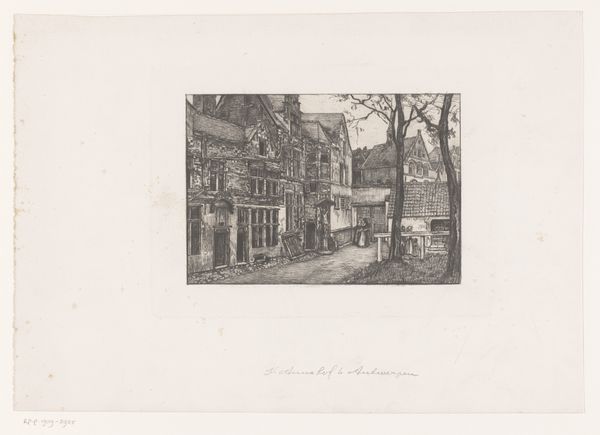

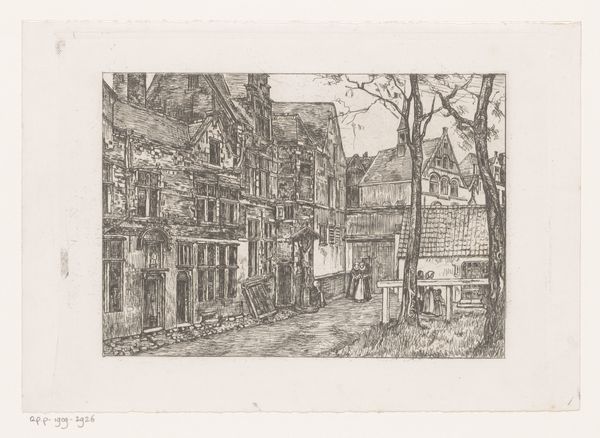

Curator: Let’s look at "Achter het tuchthuis te Amersfoort," or "Behind the Penitentiary in Amersfoort," a cityscape created in 1828 by Cornelis van Hardenbergh, housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought is, there’s a remarkable stillness in this etching, despite it depicting a place associated with restriction and perhaps turmoil. The light is soft, almost melancholic. Curator: Absolutely. We can consider the function of prisons, and who they disproportionately impact in the early 19th century in the Netherlands. Who was seen as "deviant" and how was that policed, controlled, and visualized? This building literally looms over the ordinary daily life occurring alongside the canal. Editor: It’s the technique itself, the precise, almost delicate etching, that interests me. This lends a strange contrast; you have this formidable structure, yet the image feels handmade, almost fragile. Curator: That etching style evokes earlier traditions, which were steeped in political dynamics reflecting state power through representational technologies. Its aesthetic contributes to both solidifying and normalizing such places and systems. Editor: The buildings themselves dominate the scene. We're reminded of the labor required not just to construct the buildings, but also to maintain the system they represent, all physically present in brick and mortar. There's an artistry, however grim, in how these materials are assembled to control space and people. Curator: By focusing solely on materials, we potentially flatten the multifaceted dynamics. The setting beside water speaks to trade and a degree of mobility. A complex narrative unfolds about punishment, societal organization, and urban expansion. How did shifts toward more carceral models of justice manifest in the material conditions of cityscapes, such as the one presented? Editor: Fair point. I hadn't thought about it in those intersectional terms. Thinking materially invites us to examine labor practices and built environments shaped by power. The details we see – stone, water, foliage - reveal something about this complex landscape. Curator: It brings to view these hidden historical dynamics. What power structures dictated the reality of a structure's prominence, and an individual’s limited visibility in shaping that dominance? Editor: Exactly, and what survives is a very intentional selection that reflects power dynamics present back then, and indeed even now. This dialogue underscores the multifaceted dimensions of viewing the past to critically see the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.