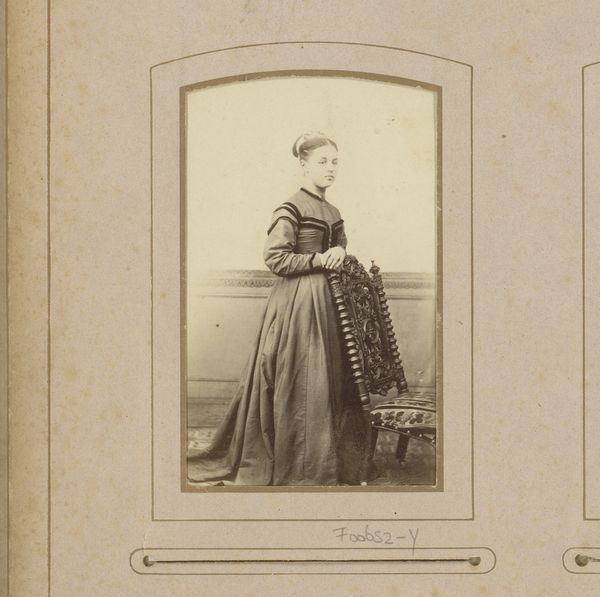

Dimensions: image: 23.6 x 17.8 cm (9 5/16 x 7 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Looking at this early photograph, there's such an intense yet subtle narrative playing out. Editor: Yes, there is a striking contrast of light and shadow here that captures my attention, and imbues the scene with an almost melancholic feel. The women are serious, caught in a moment of… what is it? Curator: Indeed. The gelatin-silver print, “Portrait of Woman and Child”, was produced around 1855 by Jean-Baptiste Frénet. Examining Frénet’s place in 19th-century France provides an illuminating framework for the reading of this image. Photography, a relatively recent invention at that time, was starting to democratize portraiture. What strikes me is how gender and class are being negotiated here through the artistic language of romanticism. Editor: The composition feels posed yet strangely intimate. The seated woman looks directly to the left, she's holding a white flower while the standing girl gazes at the seated woman as if she's looking for acceptance or silently delivering something... This highlights complex issues of class within familial relations and gender roles of the era, wouldn’t you agree? The flower seems quite symbolic. Curator: Precisely. Consider the flower in relation to the historical discourse surrounding women during this era. Often linked with themes of beauty, fragility, and domesticity, flowers could serve as potent symbols encoding social expectations and moral virtues. Also, looking at how the girl seems to be serving, and maybe a hidden reference to family labour at the time. This photographic genre itself challenges previous portrait painting norms by capturing likeness at an accessible cost to bourgeois audiences. Editor: How was photography shaping broader perceptions and social constructs around female identity back then? This photograph, especially, is like a historical artifact. I also imagine, looking at the composition, that the photograph attempts to portray not merely physical appearance, but inner states. Curator: Precisely. I see it as actively shaping, questioning, and memorializing gender and class through its formal strategies, and its place within the 19th-century social landscape of France. It serves as a powerful touchstone for revisiting how we think about photographic art's public role then and even now. Editor: Yes, it seems this is an archive not merely of documentation but of contested identities rendered visible through light and shadow. Curator: It indeed prompts deeper reflection on intersectional identities, agency, and representational power in the nineteenth century. Editor: And allows us a view of how cultural shifts materialize, shaping how women present themselves to the world in an era caught between Romanticism and revolution.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.