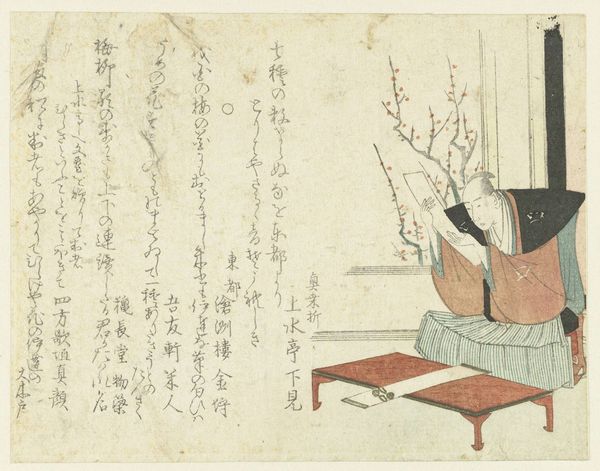

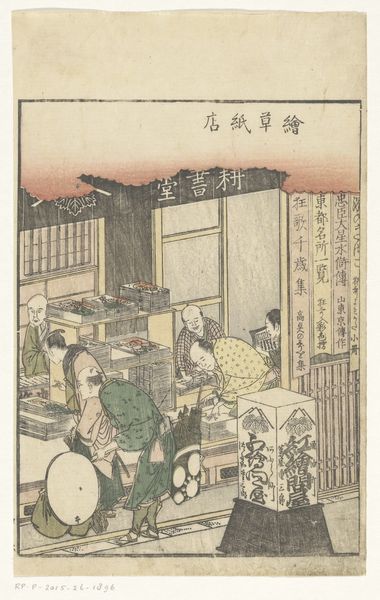

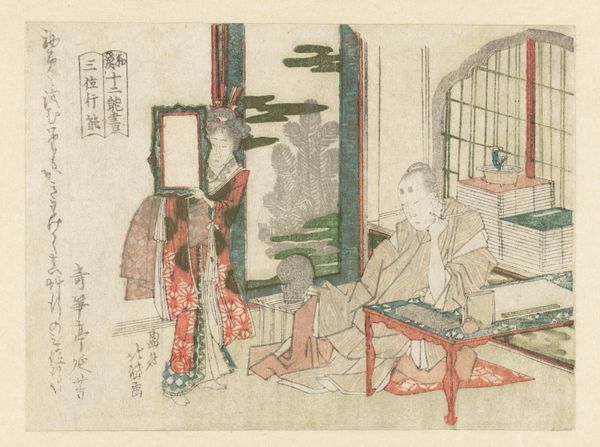

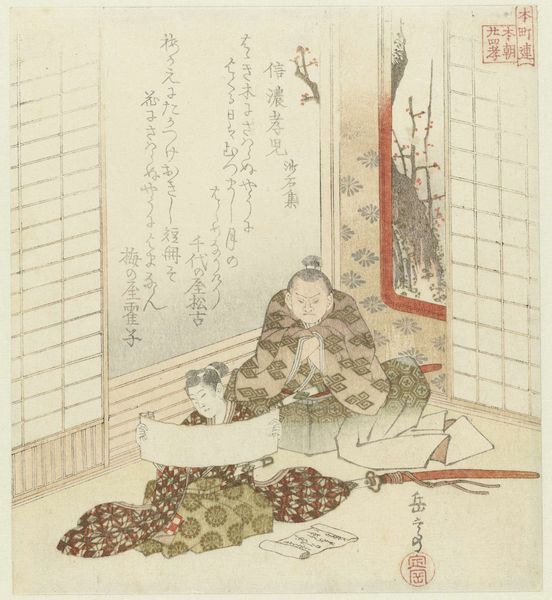

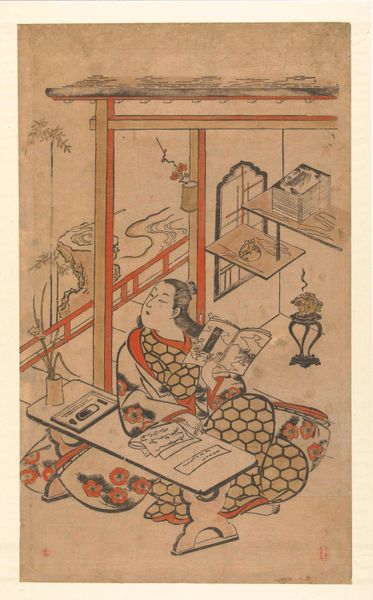

Man Seated With His Reading and Writing Materials before Him 1750 - 1835

0:00

0:00

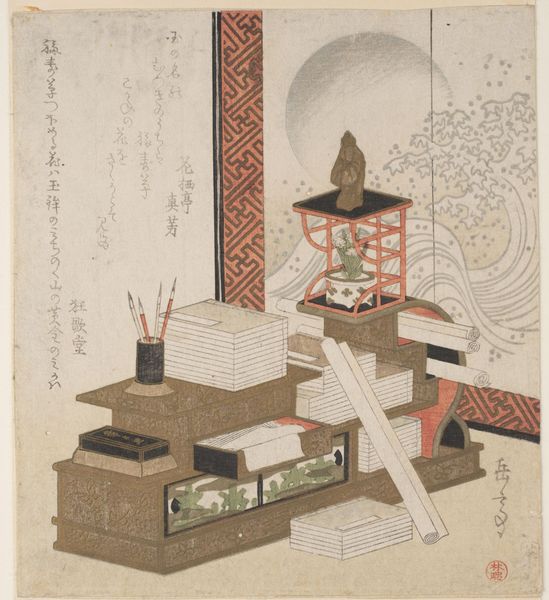

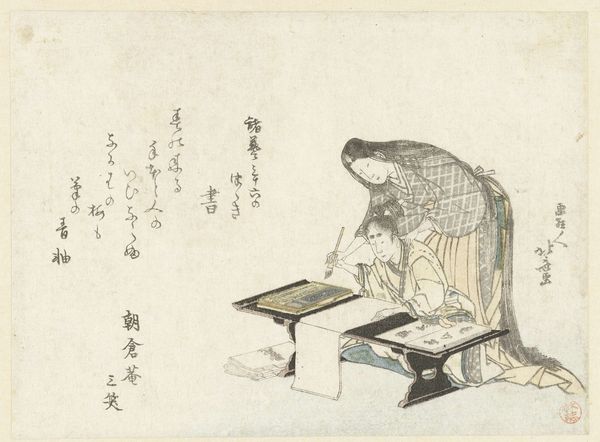

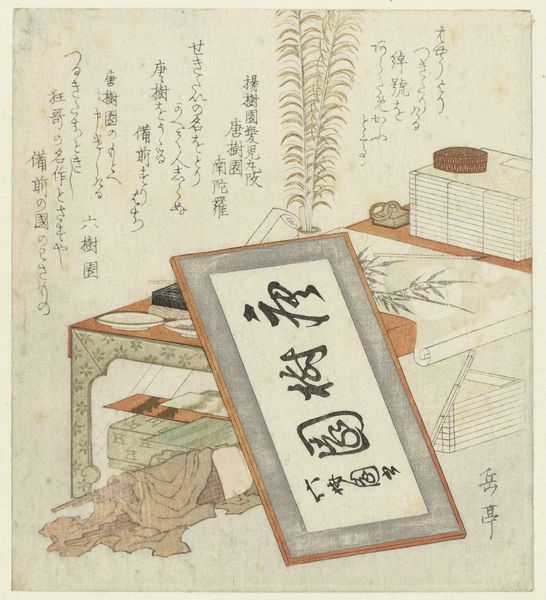

print, paper, ink, woodblock-print

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

# print

#

book

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

paper

#

ink

#

woodblock-print

#

men

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 5 3/8 x 7 3/8 in. (13.7 x 18.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This print by Ryūryūkyo Shinsai, made between 1750 and 1835, offers a glimpse into the world of a seated man surrounded by his writing and reading materials. It's currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: There’s an almost serene quality to the scene; a sense of quiet industry in the placement of objects, in the rendering of light, it seems quite intimate in scale. Curator: Indeed, Shinsai masterfully uses the woodblock printing technique, creating layered textures on the toned paper. It's categorized within the Ukiyo-e tradition, offering snapshots of everyday life, celebrity culture, and landscapes that defined the era. His chosen style seems to invite the viewer to meditate on how scholarship creates both meaning and a position in Japanese culture. Editor: Thinking materially, consider the handiwork involved in Ukiyo-e. We are seeing an end product of many roles, skills, and trades such as the woodworkers creating the blocks to print upon, the papermakers turning raw material to surfaces receptive to pigment, the binders stitching books which contain learning for their readers. These objects show labor and resources. The act of writing itself is labor that requires time, reflection, and craft. Curator: You highlight important considerations that underscore how Shinsai situated this scene as representative of its own culture; access to literary production can be seen through the depicted accoutrements, which invites conversations surrounding class and knowledge. Who could have accessed this image? What level of literacy and cultural understanding would have been required? Editor: Right, these are potent reminders that art objects are commodities as much as tools. This makes me consider the contemporary value that Ukiyo-e prints held and their reception—were they highly sought-after and collected? Curator: Good questions. The Ukiyo-e tradition often highlights transient, fashionable culture, suggesting it wasn't necessarily meant for the ages, at least initially. That makes the survival and current presence of works like this particularly meaningful for what we learn today. Editor: So, in studying the tangible, in examining the image making itself, it exposes the cultural context, and its ability to survive and be meaningful today is as dependent on cultural shifts as its initial creation. Curator: Absolutely. Seeing its legacy allows us to appreciate Shinsai's work not merely as a historical artifact but as an ongoing dialogue across centuries. Editor: Agreed. Analyzing this piece has brought out complex thoughts around both the power of creation, preservation, and legacy that echo across eras.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.