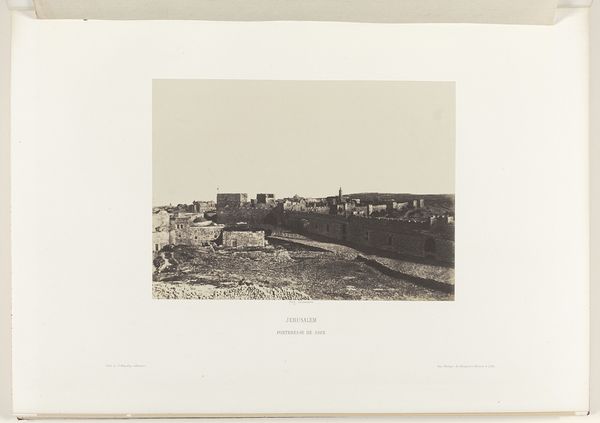

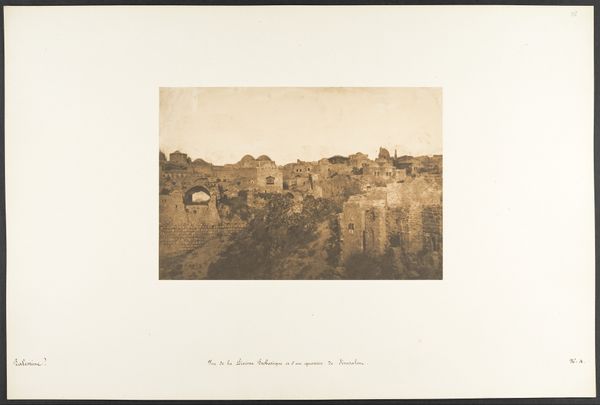

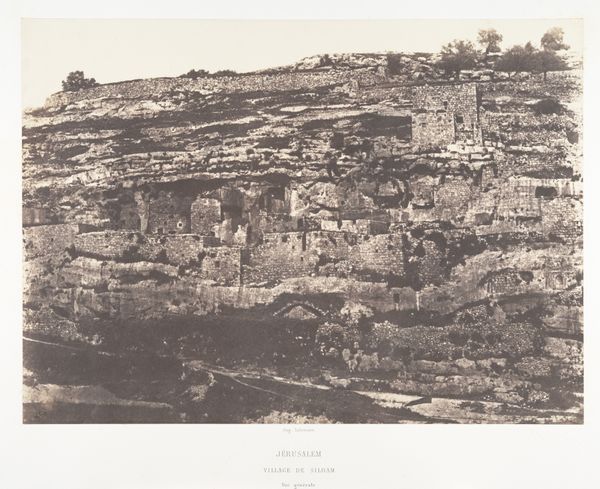

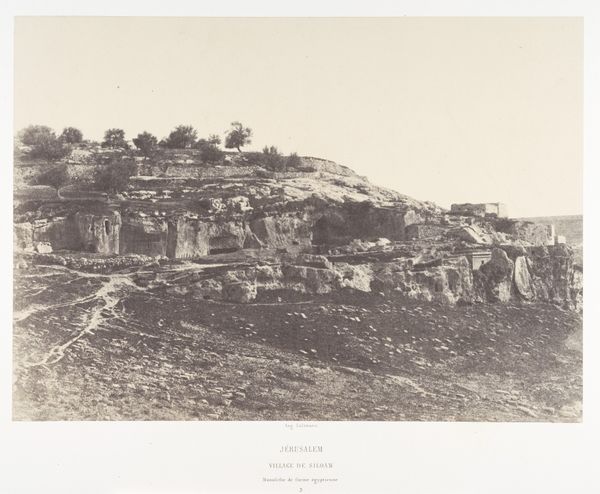

Bekken van Birket-es-Soultan buiten de oude stadsmuur van Jeruzalem 1854 - 1856

0:00

0:00

print, daguerreotype, photography

#

16_19th-century

# print

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

orientalism

Dimensions: height 155 mm, width 218 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

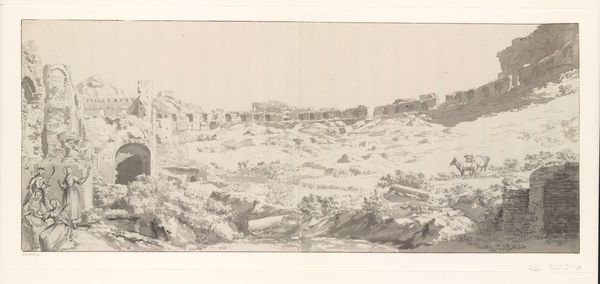

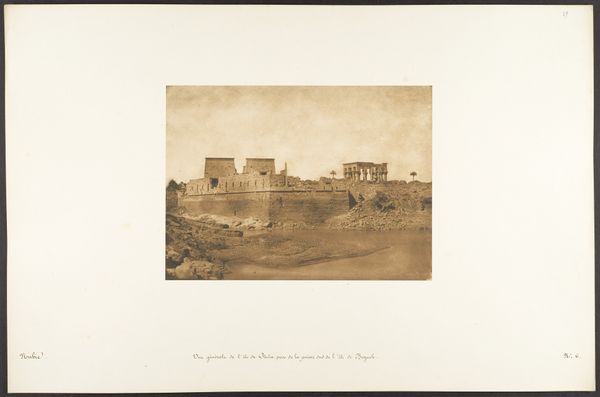

Curator: Gazing upon this image, I'm immediately struck by a profound sense of stillness. There's an almost melancholic atmosphere evoked by the soft sepia tones. Editor: Indeed. This is "Bekken van Birket-es-Soultan buiten de oude stadsmuur van Jeruzalem," or the Birket-es-Soultan Pool outside the old city walls of Jerusalem. Auguste Salzmann captured it between 1854 and 1856 using the daguerreotype process, a very early form of photography. Curator: Ah, that explains the dreamy, ethereal quality. It’s like looking into a faded memory. The city walls, etched against the horizon, feel both imposing and vulnerable. Editor: Salzmann's work is fascinating from a postcolonial perspective. It intersects with the European fascination with the "Orient," a constructed geography fueled by specific political and aesthetic agendas of that era. Photography, in this context, became a tool to document, possess, and ultimately exoticize landscapes and cultures. Curator: You’re so right. Even the composition leads my eye—sort of like I’m staging it. I can almost smell the dust and sun-baked earth. This city, ancient and sacred, appears under such quiet scrutiny, with not a soul in sight. It really underlines the sort of Western gaze in Orientalism and photography back then. Editor: Precisely. While celebrated for its documentary value at the time, we must also interrogate these images, asking ourselves: Whose story is being told? Whose perspectives are centered? And, perhaps more importantly, whose are being erased? Look, for instance, at how the image focuses on architecture, depopulating and flattening the social landscape by framing it as something for the colonizer’s possession. Curator: Food for thought… it's intriguing how something intended to record reality could be such an interpretation, if not misrepresentation. It leaves me questioning my own response, even my own fascination with the piece. Editor: I agree. By grappling with these contradictions, and questioning the photograph’s agenda, we can build a more honest narrative, using historical objects not just as records of the past but as a roadmap toward justice and equality. Curator: Well, that makes me feel so hopeful to see that the beauty in old pieces like this lies beyond first appearances, but even more about our discussions about the complex layers to the landscape it contains.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.