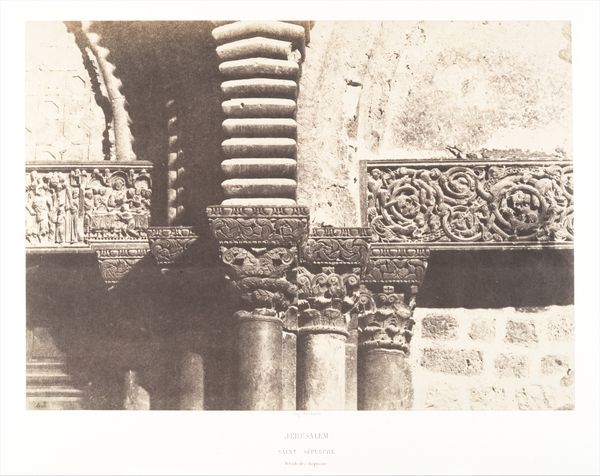

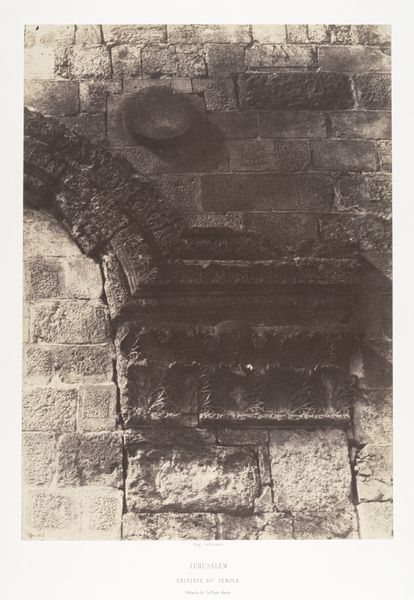

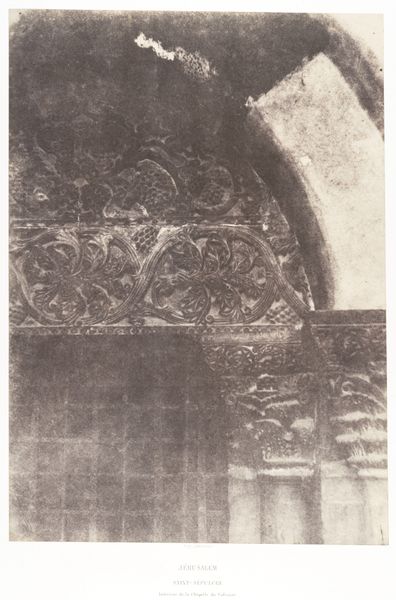

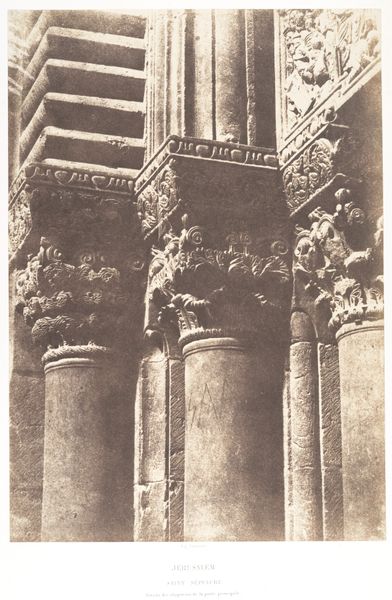

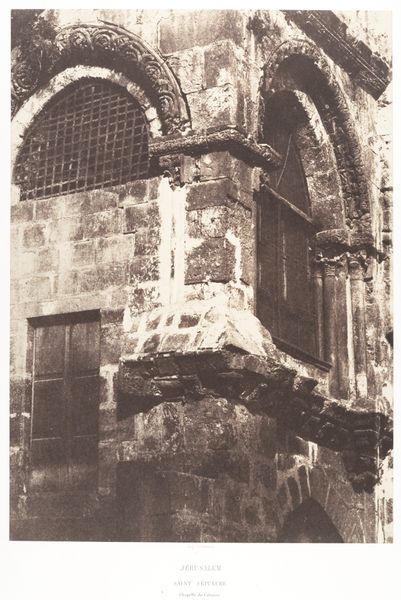

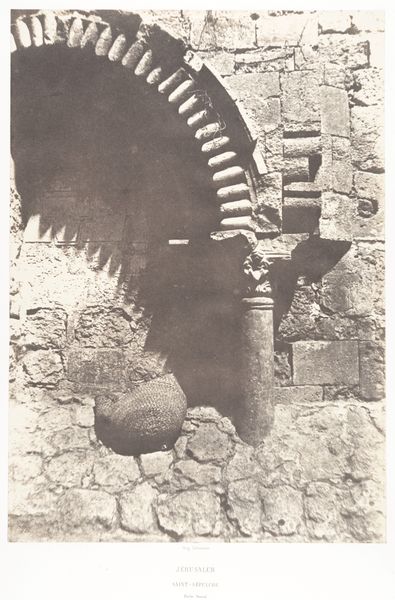

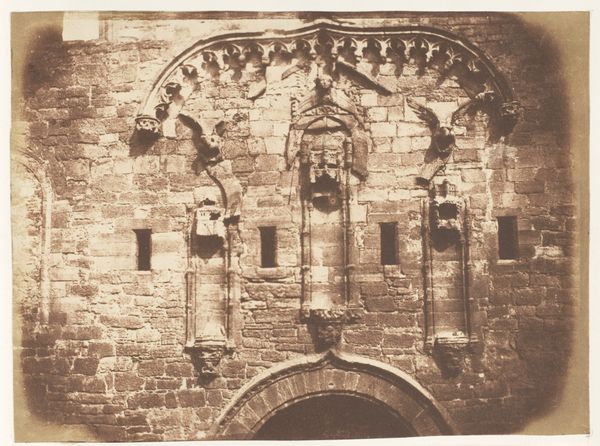

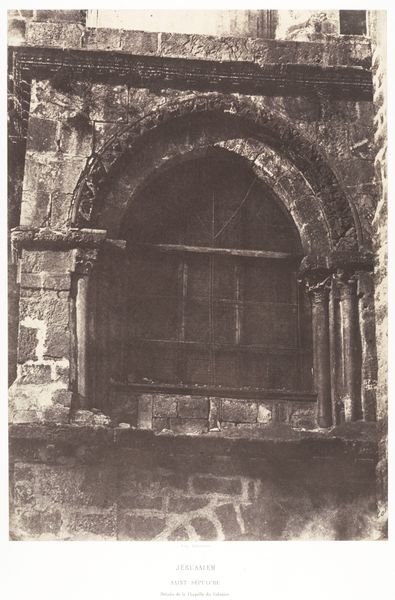

Jérusalem, Saint-Sépulcre, Détails de la porte 1854 - 1859

0:00

0:00

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

# print

#

landscape

#

form

#

photography

#

romanesque

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

line

#

architecture

#

realism

Dimensions: Image: 32.3 x 23.3 cm (12 11/16 x 9 3/16 in.) Mount: 60.3 x 44.7 cm (23 3/4 x 17 5/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is "Jérusalem, Saint-Sépulcre, Détails de la porte," a gelatin silver print taken by Auguste Salzmann sometime between 1854 and 1859. There's such an intense sense of history and texture here. It's hard to believe it's a photograph; it almost feels like I’m looking at an architectural drawing. How do you read this work? Curator: Salzmann’s photographs of Jerusalem are particularly fascinating when we consider the burgeoning European interest in archaeological and biblical sites during the mid-19th century. He wasn't simply documenting; he was participating in a wider project of constructing and reinforcing certain narratives about the region. Do you notice how he isolates this particular section of the door? Editor: Yes, it really emphasizes the details – the carved capitals, the texture of the stone… Curator: Exactly. Consider the historical context: photography was still a relatively new medium. By focusing on architectural details like this, Salzmann almost lends a scientific air to his work, reinforcing the idea of objective documentation. Yet, this image also played into colonial power dynamics. Whose story was being told, and for whom? Were these images intended to foster understanding, or to subtly assert dominance through representation? Editor: So, it's less about pure representation and more about shaping perception, even back then. Curator: Precisely. It's about controlling the narrative. These photographs were not just seen; they were consumed within a very specific European intellectual and political landscape. This work contributes to the construction of an orientalist discourse. What do you think of the public perception and access of such imagery? Editor: That makes me rethink my initial reaction. What seemed like simple documentation now appears loaded with implications about power and representation. Curator: And that is precisely the importance of looking beyond the surface and considering the social and political context in which art is created and received. Editor: Thank you. Now, seeing through the lens of colonial power, it has become so much more than beautiful stonework to me.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.