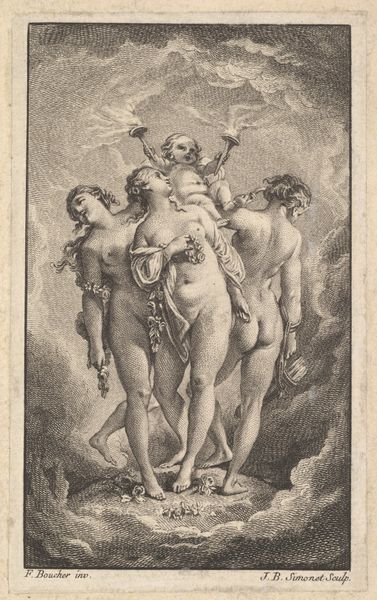

The Three Graces sitting on clouds, cupid at the left, after Raphael's fresco in the Chigi Gallery of the Villa Farnesina in Rome 1512 - 1525

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

female-nude

#

cupid

#

pencil drawing

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: 12 3/8 x 8 1/4 in. (31.4 x 21.0 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

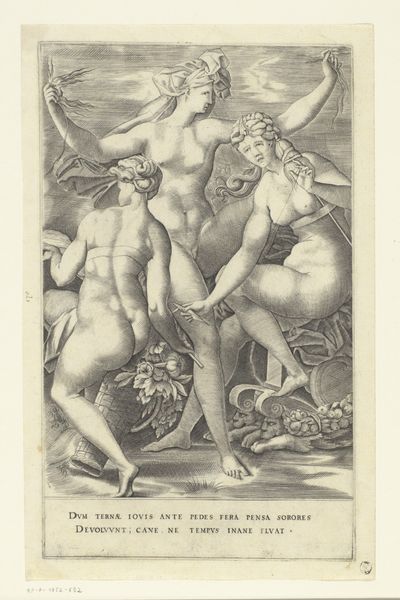

Curator: Here we have Marcantonio Raimondi’s print, "The Three Graces sitting on clouds, cupid at the left, after Raphael's fresco in the Chigi Gallery of the Villa Farnesina in Rome," created sometime between 1512 and 1525. Editor: It's stark. The monochromatic etching casts a solemn, almost grave air around what is supposedly a scene of grace and beauty. Curator: Raimondi masterfully uses engraving to replicate the textures and tones of Raphael's original fresco, showcasing a key moment in the Renaissance appropriation of classical forms and ideals. He provides a network for understanding and distributing these forms on the material and public sphere. Editor: Structurally, the composition leads the eye in a tight curve, from the putto to the faces of the Graces, contained within the arch. It emphasizes their connectedness, while the cloudscape, acting as the fulcrum for the three graces, seems too concrete, and fails to invoke true airiness or ethereality. It lacks depth, a consequence of engraving? Curator: Partly. Engravings like these facilitated the dissemination of Raphael's artistic style throughout Europe. Its popularity rests not only on its inherent formal beauty, but also on its capacity to showcase Italian cultural achievements for patrons across courts. Note also the emphasis of the nude, in a moment of intense cultural fascination with antiquity. Editor: These figures, they lack individual character. Is it an intentional feature of the classical ideal—these generalized forms which point more directly to underlying structure? The surface qualities yield to geometric patterns beneath, calling more attention to its architecture of lines and shapes. The texture gives volume but little personal detail or even emotion. Curator: It certainly prioritizes the idealization over the individualized. I’d also point to the engraving technique, the meticulous detail balanced with the clean, spare lines, reflects the Renaissance's renewed interest in classical precision and clarity. Editor: So in effect the style and reproduction method act to enforce classicism. I find myself almost unable to reconcile with their lack of feeling. This lends a distinct air of cool calculation to the image as a whole. Still, considering it in a semiotic relationship to its cultural moment as you say makes me view the whole structure more analytically, with greater appreciation. Curator: Precisely. Its appeal lies as much in its intellectual underpinnings as its visual allure. Editor: It's shifted how I perceive both content and method here; considering it as evidence gives new texture to an otherwise rigid work. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.