photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

portrait reference

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

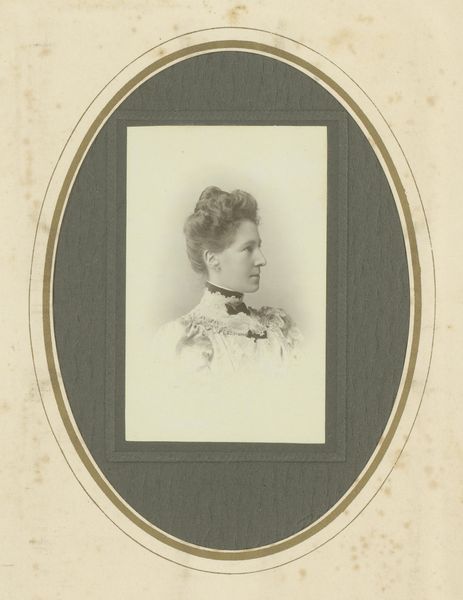

Curator: Allow me to introduce a captivating piece from the Rijksmuseum’s collection: a photographic work entitled "Portret van een vrouw met ketting," or "Portrait of a Woman with a Necklace," attributed to Max Büttinghausen, and dated between 1886 and 1906. Editor: The tonal range here is incredible, from the bright whites of the gown to the muted grays describing her features. There’s an undeniable stillness to the photograph, a calm elegance almost radiating from the woman's poised posture. Curator: Note how the photographic medium allows for a striking interplay of light and shadow. Consider the meticulously rendered textures – the intricate lace of her collar, for example, offset by the subtle sheen of the necklace itself. It's almost as though the image seeks to elevate the sitter to an ideal. Editor: What fascinates me, though, is how the creation of such a portrait demanded labor, materials and time. The development processes in those years would involve mixing and handling light-sensitive chemicals – a whole performative act behind the scene of this supposedly “static” moment. How did posing for this new technology transform her daily understanding of labor and representation? Curator: You make a vital point regarding materiality. Yet, observe how Bütthinghausen harnesses the photographic technique not to present mere reality, but to achieve something more, how the formal arrangement leads us to an ideal aesthetic of feminine poise and restraint. Editor: Restraint maybe, but the abundance of fabric and jewels speaks volumes about material wealth, and thus access. Was this privilege on display specifically to impress, and what economic activities underwrote this performance of wealth? These early portraits always strike me as intensely class-conscious objects, meant to solidify social positions. Curator: Perhaps. The composition's subtle asymmetry generates visual interest as her gaze avoids ours; nonetheless, such restraint underscores the conventions of portraiture, its construction as an exercise in controlled revelation. Editor: So true – but let us also reflect that these early portraits offered women in particular new avenues of visibility. While adhering to conventions, she is nonetheless there, present and framed – owning her image through participating in the photographic event. Curator: Indeed. This small artifact provides such rich layers to interpret through the evolution of photographic language. Editor: Absolutely! By considering these artifacts materially, it sparks essential questions around wealth, access and historical experience.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.