Dimensions: height 92 mm, width 57 mm, height 104 mm, width 64 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

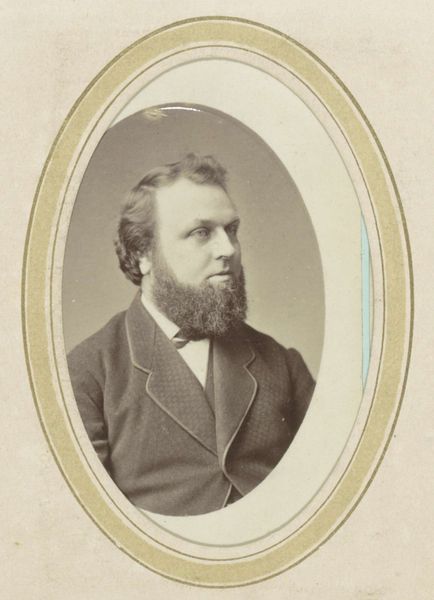

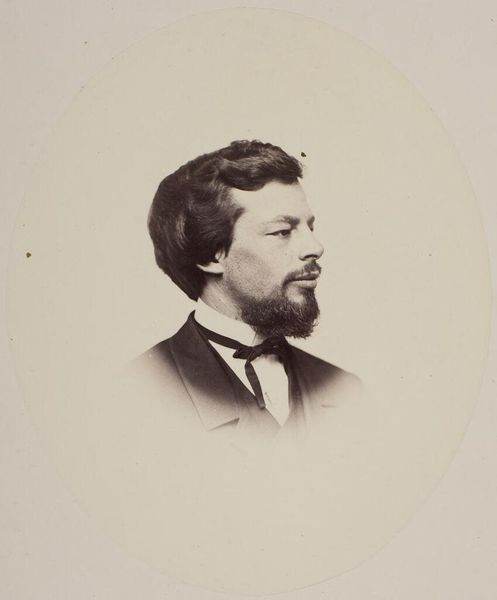

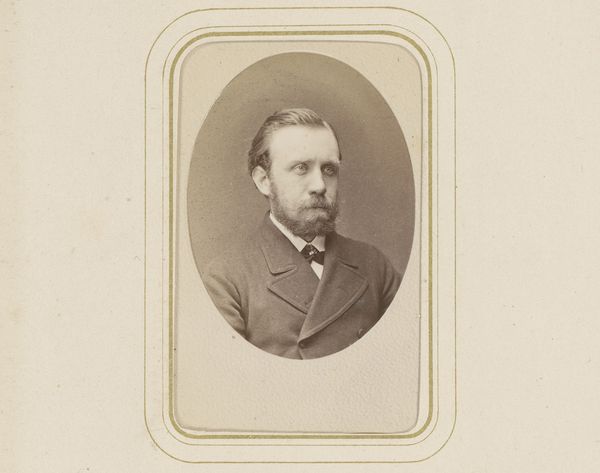

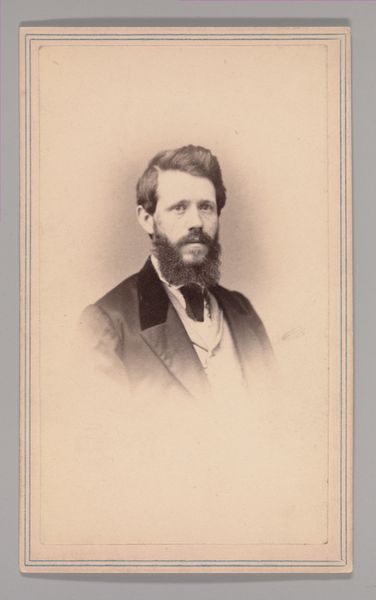

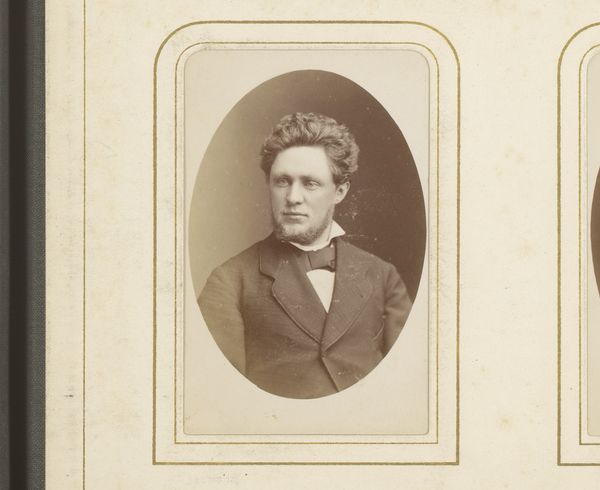

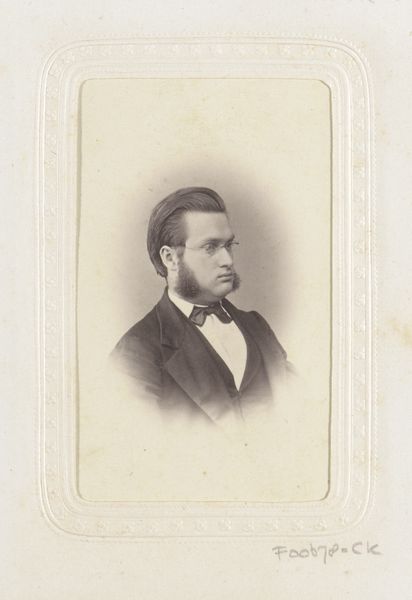

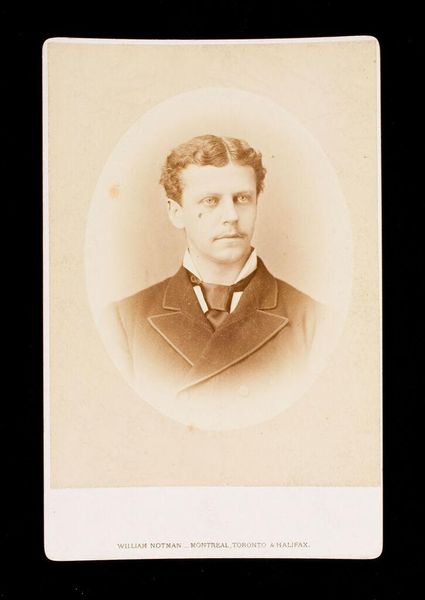

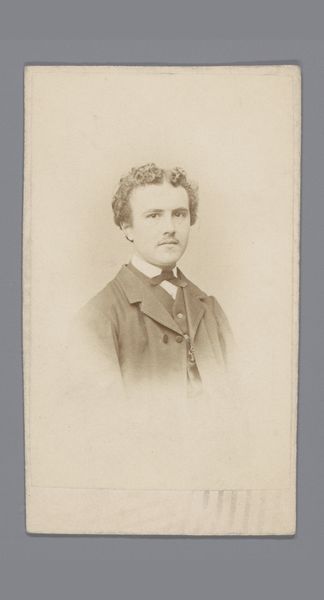

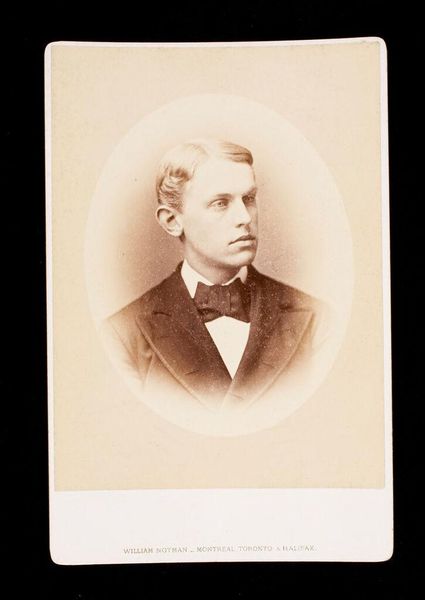

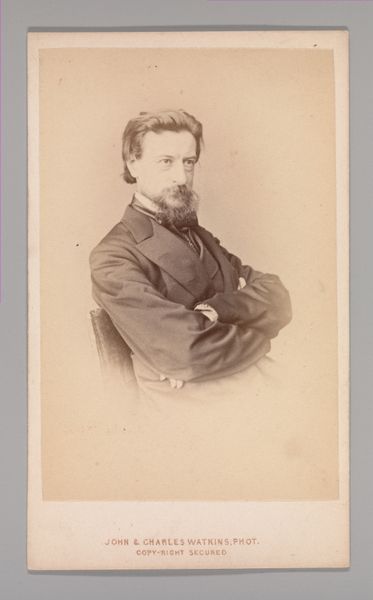

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, titled "Portret van een man met bakkebaarden en een strik," produced between 1874 and 1890 by A. Böeseken, captures a man in striking detail. There is much we can read from this image in terms of industrial processes, photographic technology and economic output that are crucial to the art historical significance of this portrait. Editor: My first thought is how staged the image feels, almost theatrical, with the stark lighting accentuating the man's rather substantial sideburns and neatly tied bow tie. It’s a study in constructed masculinity. Curator: Absolutely. The material itself - the gelatin-silver process- marks a shift in photography from earlier, more cumbersome methods. This allowed for mass production of images and dissemination into larger populations of the time. The ability to have standardized portraits increased visibility for bourgeois sitters but further separated those who were marginalized and lacked these resources, furthering established class differences in the Victorian era. Editor: It certainly speaks to power dynamics, doesn't it? The careful grooming, the formality of the attire—it projects an image of respectability and status that undoubtedly plays into the social and political narratives of the time. Whose stories were considered worthy of preservation and dissemination? Curator: Precisely. And beyond just "respectability," how do labor practices enter the discourse? These portraits required workers in factories to create, develop, and mass produce these standardized images. So much work from so many to propagate an aesthetic ideal. What would the worker who manufactured the glass plate think of its intended user? The artistic merit is thus found not in the isolated art object but through these interconnected industries that reflect hierarchies, the cultural, and power dynamics between individuals who appear in them and the world that enabled their proliferation. Editor: Looking closer, there's a vulnerability, I think, beneath the posed composure. The eyes hint at something more complex, a silent story. The image's realism and careful attention to detail evoke the subject's life and emotions and provoke conversation on historical perception of men, masculinity and standards for presentation. It's both a formal portrait and, perhaps unintentionally, an intimate glimpse into a past era. Curator: Indeed. Examining not just what’s pictured but how and why opens pathways into larger historical and cultural dialogues of representation and production of that period. Editor: A rich photograph, prompting inquiries that question everything from industrial output to gender studies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.