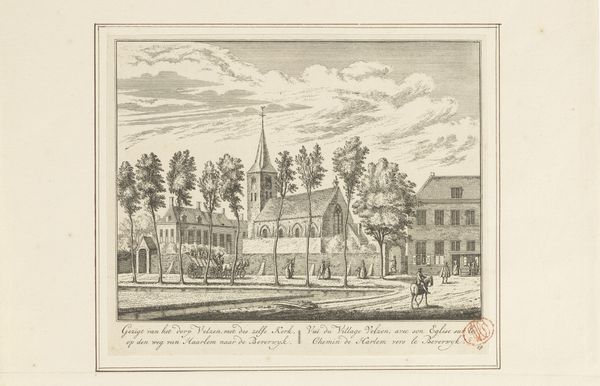

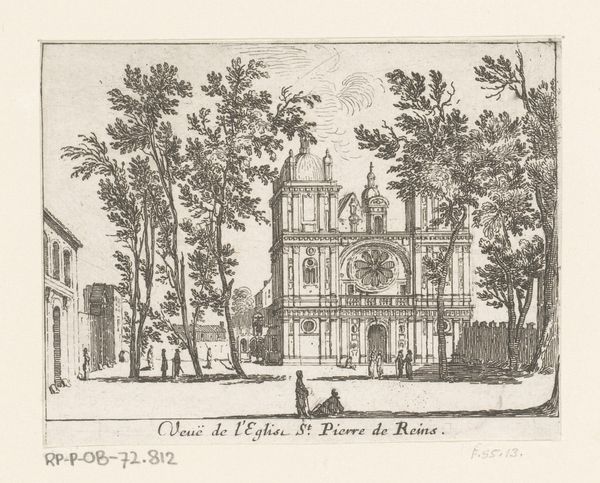

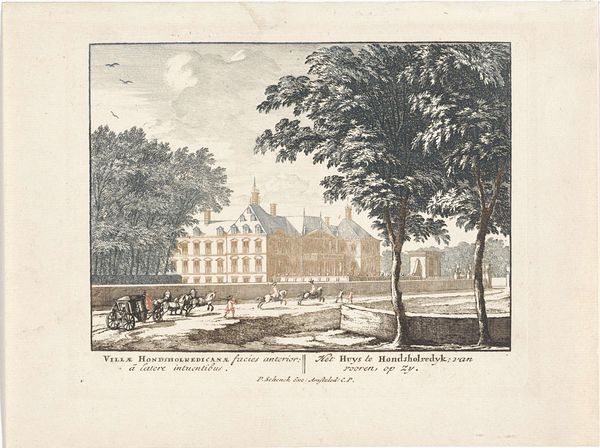

print, etching, engraving

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

historical photography

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 82 mm, width 110 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us we have Hendrik Spilman's "Gezicht op de Waag te Oudewater, 1745", an engraving and etching dating from approximately 1750 to 1792. It is currently held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It possesses a rather serene mood, doesn't it? The balanced composition, punctuated by the weight house, has an almost mathematically precise appeal. I wonder about its deeper structural intents. Curator: Indeed. Spilman's rendering captures the visual reality of Oudewater in a period where civic identity was heavily invested in symbols of commerce and communal life. The weigh house wasn’t just a building; it was the cornerstone of trade and local economy, prominently placed for all to see. Editor: Absolutely. Consider the way Spilman manipulates light and shadow. The stark contrasts not only define forms, creating volume and depth, but also direct our eye—leading us into a careful parsing of spatial relations and proportional harmonies, I see what appears to be a social theater. Curator: The presence of figures invites speculation, don't you agree? Notice the figures standing just outside the weigh house; perhaps discussing business, marking a key social gathering spot that facilitated the exchange of information alongside goods? The social infrastructure is vital. Editor: That's insightful. Let’s analyze the architecture itself, where Spilman showcases a detailed understanding of form. Observe the geometry, specifically, how vertical lines of the facade interact with horizontals across the buildings and street to produce tension; each contributing to a semiotic narrative wherein order is paramount. Curator: This kind of detailed portrayal offered viewers a tangible connection to their world, fostering a sense of civic pride. Prints such as these were distributed widely. They shaped and reinforced particular notions about places, values, and collective experiences within Dutch society at the time. Editor: Thinking about the materiality also strikes me as necessary. We are viewing an etched and engraved image. I am struck by the textural complexities achieved. These add layers to the discourse between the artist's idea and execution as an ideological operation that mirrors the socio-economic reality. Curator: Understanding the historical function illuminates the artist's choices—reflecting not just an objective landscape, but carefully constructing communal memory by choosing certain subjects of civic value like trade infrastructure, architecture, and local residents that continue influencing social perceptions of place and time. Editor: Indeed, seeing through the dual lenses—form and history—the work transcends documentation, revealing insights into 18th-century Dutch life while exemplifying fundamental aesthetic principles governing the epoch.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.