Dimensions: height 103 mm, width 115 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

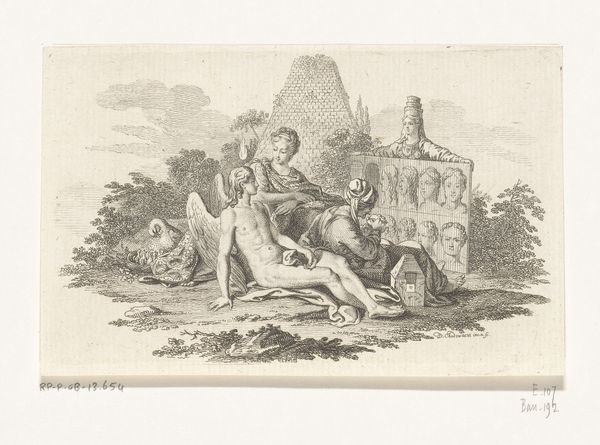

Curator: This is Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki's "Vriendschap en Hoop naast een urn," created around 1770. It's an engraving held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It strikes me immediately as delicate, almost fragile. The thin, precise lines of the engraving lend it an airy, ethereal quality, despite the heavy subject matter of mourning. Curator: Indeed. Chodowiecki was known for his engravings, often tackling moral and historical subjects within the context of 18th-century social commentary. The piece leans heavily into allegory, common in that era, personifying abstract concepts like Friendship and Hope. Editor: Look at the urn itself. It's meticulously rendered, each individual basket weave detail painstakingly etched. The contrast between its tangible form and the more nebulous "Hope" figure beside it is compelling. It really roots the symbolic in the physical reality of loss. Curator: The imagery plays with prevalent philosophical ideas of the time. Note how Friendship, draped and sorrowful, physically clings to the urn, whereas Hope gestures upwards, signifying something beyond earthly grief. The anchor at Hope's feet? A symbol of steadfastness, a kind of faith during hardship. Editor: That anchor grounds her, literally and figuratively. The act of engraving itself, with its reliance on craft and precision, parallels that steadfastness, wouldn't you agree? You can’t rush the process; each line requires a deliberate act, a dedication to the material. It feels like an act of slow, considered labor mirroring the long process of grieving. Curator: Certainly. And don’t overlook the role prints played at that time, either! Reproductions allowed images, and thus ideas, to disseminate rapidly through society. Chodowiecki wasn't simply creating a beautiful object; he was actively contributing to a larger discourse on grief, virtue, and resilience. Editor: So, considering the material then – engraving – helped deliver a moral lesson, it makes you wonder if these weren’t somewhat ubiquitous objects within 18th-century households. It’s easy to imagine copies reproduced en masse, making accessible and relatively inexpensive works that performed important social functions. Curator: Exactly! This work provides an interesting insight into the artistic values and concerns of its historical context. Editor: Seeing the labor-intensive detail reminds us of art’s social context – its place in popular life and material culture beyond simply high art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.