drawing, print, etching, paper, ink

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

paper

#

ink

Dimensions: sheet: 9 3/16 x 7 3/16 in. (23.3 x 18.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

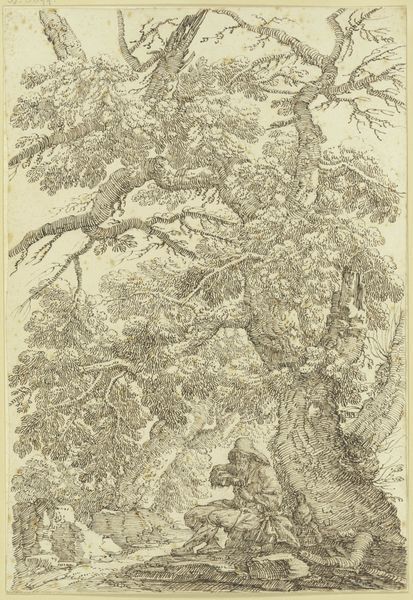

Editor: Here we have Gillis Neyts' "Study of an Old Tree," dating from between 1635 and 1687. It's an etching in ink on paper, currently residing at the Met. I’m really struck by the sheer volume of lines used to depict the tree's foliage. What catches your eye? Curator: I’m immediately drawn to the labor embedded in this etching. Think about the repetitive, almost meditative act of creating these myriad lines. This wasn't a quick sketch, but a deliberate process of translating the organic into a reproducible, and therefore marketable, image. How does the choice of etching, a printmaking process, affect our understanding of the artist's intent compared to, say, a unique drawing? Editor: Well, the reproducibility means it wasn't a singular object but made to circulate and become available to many. Did that impact its perceived value or function then? Curator: Absolutely. Etchings like this became commodities, filling a demand for accessible landscapes amongst a burgeoning middle class. Consider also the paper itself—its sourcing, production, the labor involved. Even the ink, its composition, origin, and trade routes all contributed to this “simple” study. Do you see a relationship between the seemingly natural subject and these complex networks of production and distribution? Editor: I guess I do now. It’s less a pure, untouched image of nature and more a product deeply embedded within economic and material realities. So, its value isn't just aesthetic but also lies in revealing those processes. Curator: Precisely. The “Study of an Old Tree” invites us to consider not just the beauty of the tree itself, but also the unseen labor and material flows that brought this image into being. Editor: I’ll definitely look at prints differently now. Thanks for helping me understand this from a material perspective!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.