photography, albumen-print

#

toned paper

#

landscape

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

albumen-print

#

realism

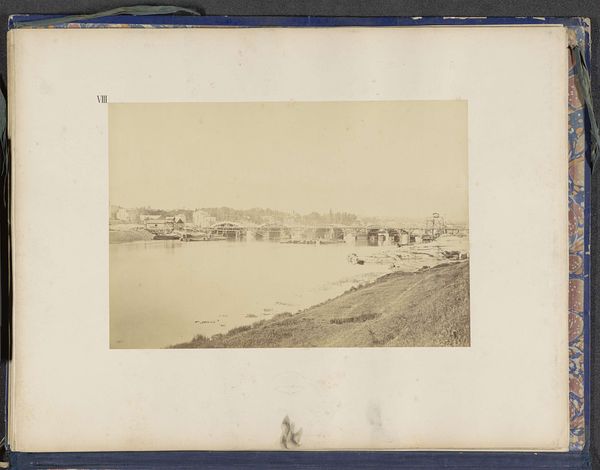

Dimensions: height 153 mm, width 190 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

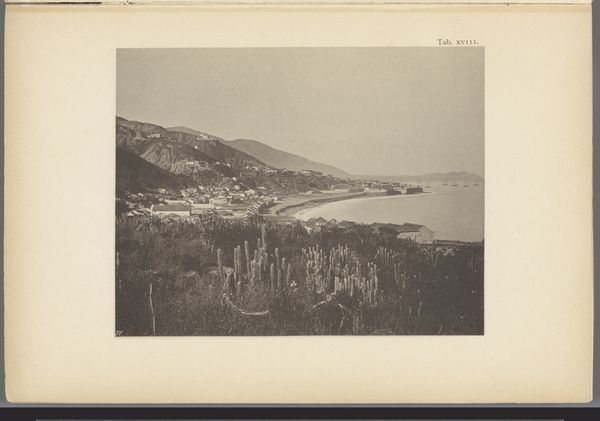

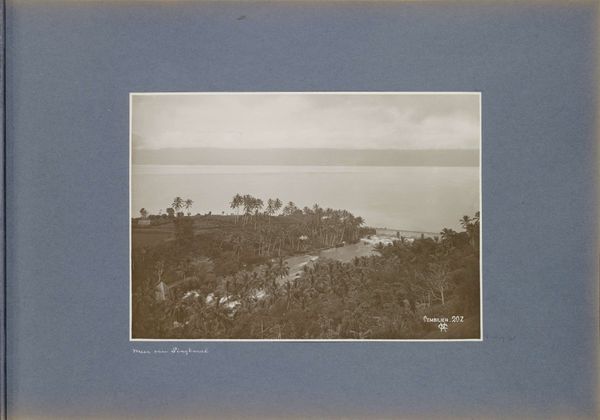

Curator: The stillness of this photograph, titled "Gezicht op een kleine haven, mogelijk op Madeira," transports me. The work is believed to have been created sometime between 1885 and 1910 using the albumen print process. The tones! Such subtlety, even in the presence of such varied textures. Editor: It’s evocative, certainly, a melancholic tranquility almost palpable through the faded print. I wonder about the dynamics between colonial trade, forced labor, and leisure evident in a port scene like this in the late 19th Century. Curator: Precisely. Images like these served multiple purposes. Beyond their aesthetic qualities, albumen prints, and photography in general, solidified Western conceptions and documentation of places distant from Europe. Photography, as a medium, was both artistic expression and also documentation for colonial regimes. Madeira, for example, as a key location along international trade routes. We need to also recognize who owned cameras during this period; these visual perspectives typically came from wealthy merchants and colonists and that viewpoint permeates what we see here. Editor: Notice the receding space. The composition directs our gaze carefully from the immediate foreground up along that winding road toward the light-drenched coast. Semiotically, it represents a constructed journey—a very prescribed way of seeing, even controlling, the topography. But is this harbor truly for everyone or, visually and materially, does it exclude marginalized communities? Curator: Absolutely. By carefully examining the visual rhetoric, and comparing that with historic records, we begin to have a clearer image of life during this time. This isn't just a neutral, observational scene, this visual construct offers encoded messaging that bolstered imperial expansion and global capitalism. These images also often idealized leisure for European visitors. But where are the narratives of local populations, of people forced to work in harbors and sugarcane fields to cater to these tourists? We rarely, if ever, see their realities represented here. Editor: What’s fascinating, then, is understanding how even the formal, compositional strategies can function as ideological signifiers. The framing itself participates in establishing power dynamics. I appreciate being nudged to contemplate this view as constructed, a fragment of history told from a selected vantage point. Curator: Agreed. Hopefully, viewing images like this within their proper historical and political context allows all of us to see them, and subsequently the world, with increasingly critical and informed eyes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.