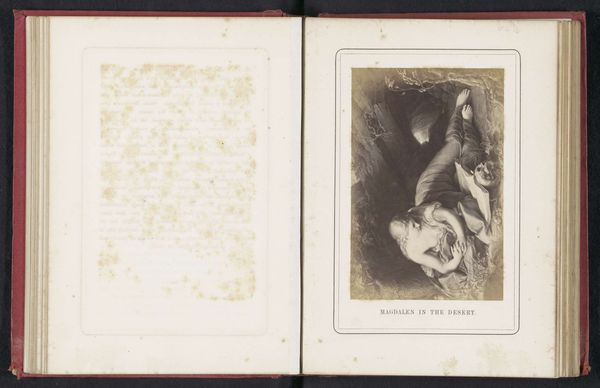

Fotoreproductie van een schilderij van een lezende Maria Magdalena door Correggio before 1864

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 103 mm, width 140 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

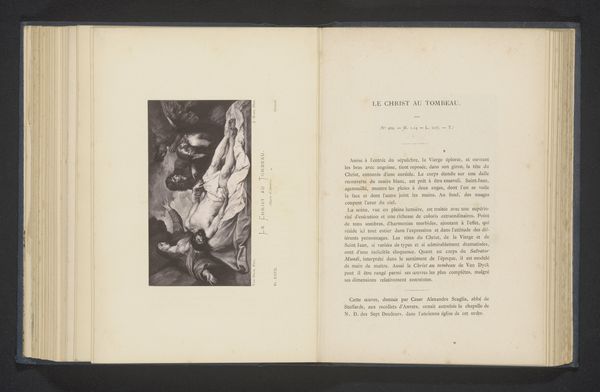

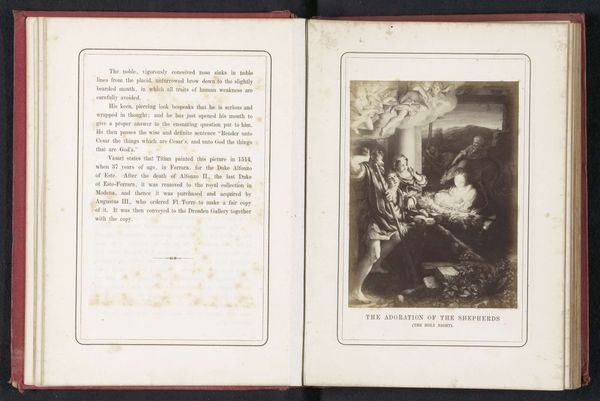

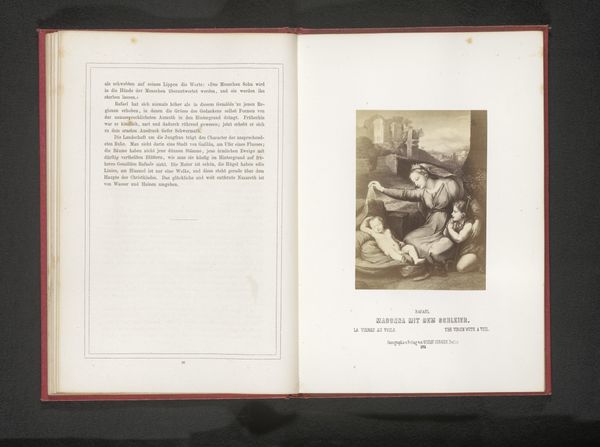

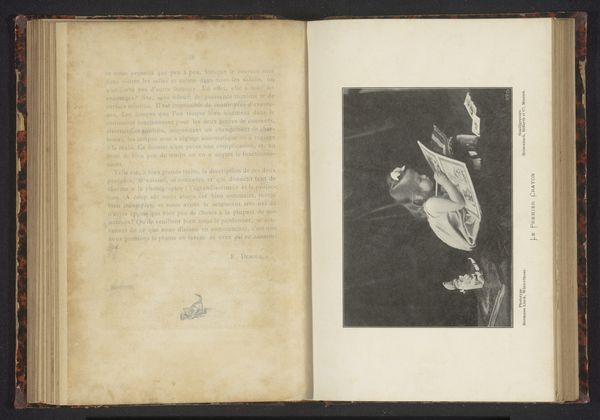

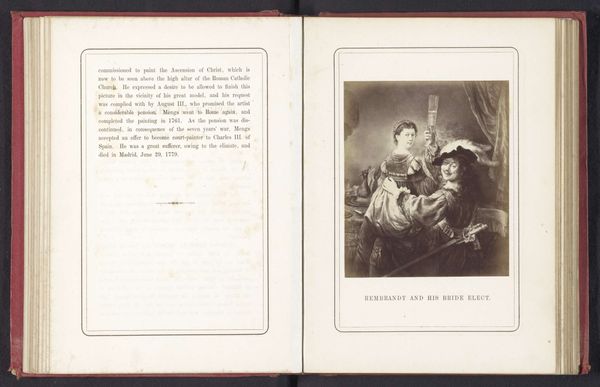

Curator: Here we have a photomechanical reproduction, made before 1864 by Hanns Hanfstaengl, of Correggio's *Penitent Magdalene*. It's printed on paper and bound in a book. Editor: It's fascinating to see this famous painting mediated through photography and print. The stark contrasts and tones created by this early photographic process give the image a unique emotional feel. What can you tell me about the reproduction process of this image? Curator: Well, the emergence of photomechanical reproduction marks a pivotal shift in how art was consumed. The ability to reproduce images cheaply and efficiently democratized access to art in ways never before imagined. Think about the labour involved: from the photographer capturing the image to the printmakers creating numerous copies. How do those processes change the perception of the original artwork and its value? Editor: It makes me wonder about the intended audience for this book and the cultural context that led to its production. Was it meant for scholars, artists, or perhaps a more general public? Curator: Exactly! This reproductive process highlights the transition of art from a unique object experienced primarily by the wealthy elite to a more widely disseminated commodity. Notice the printed text accompanying the image—this speaks directly to its role in educating a growing public about art history and religious narratives. It is about the act of circulation and knowledge dissemination. How does this process intersect with prevailing ideas about art, religion, and social class in the mid-19th century? Editor: So, looking at it this way, the photomechanical reproduction itself becomes a lens through which we can understand broader shifts in artistic production and consumption during the 19th century? Curator: Precisely. It prompts us to consider art not just as an isolated aesthetic creation, but as part of a complex social and economic network, impacting the lives of those involved in the labour of producing, distributing and using this artwork. Editor: It’s eye-opening to realize that this seemingly simple photographic reproduction speaks volumes about the changing landscape of art production and accessibility. Curator: Indeed, understanding art necessitates a materialist lens, urging us to ask questions beyond aesthetics and to consider the intricate systems and historical narratives surrounding its creation and dissemination.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.