#

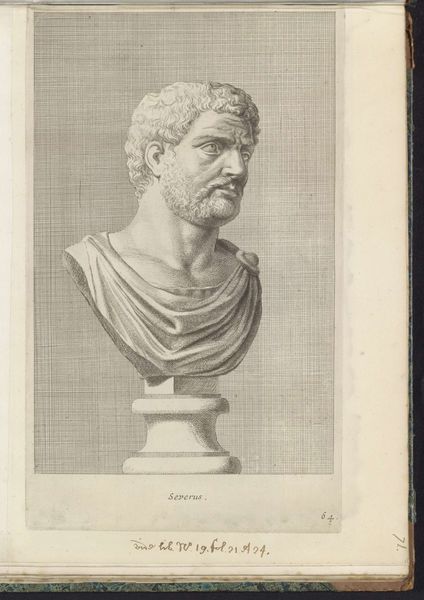

photo of handprinted image

#

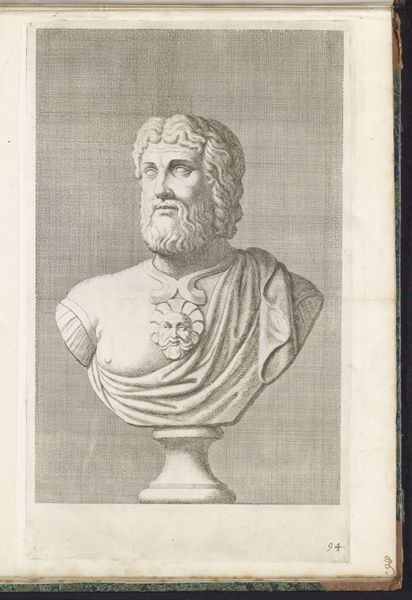

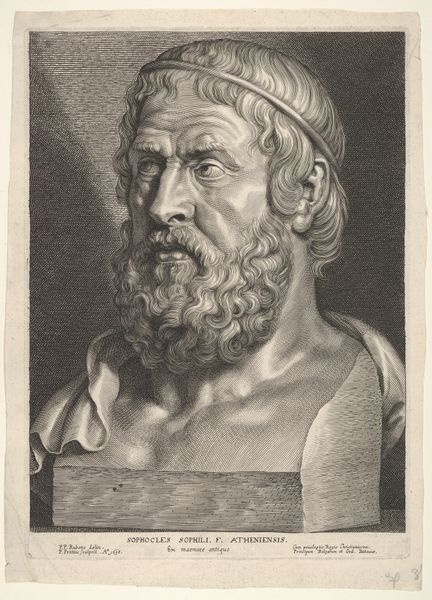

statue

#

picture layout

#

photo restoration

#

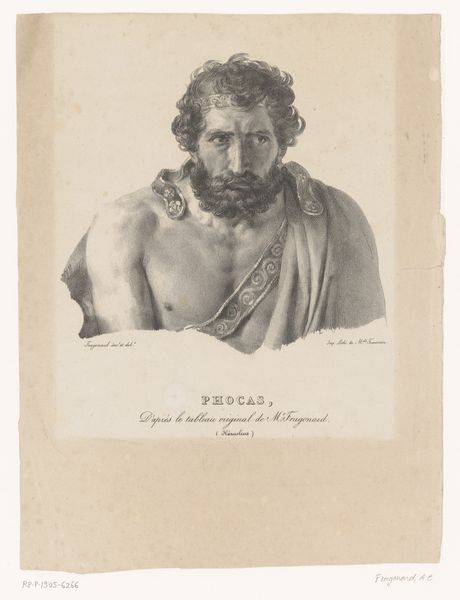

expressing emotion

#

portrait reference

#

strong emotion

#

yellow element

#

photo layout

#

portrait drawing

#

tonal art

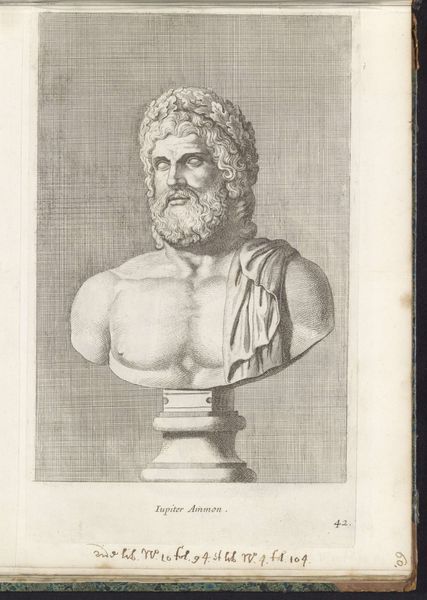

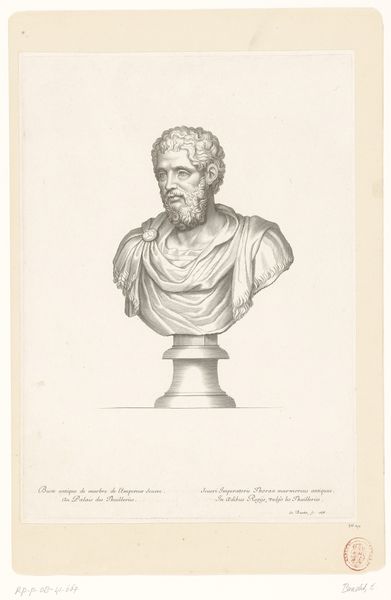

Dimensions: height 320 mm, width 251 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately, I notice the stark greyscale rendering of this bust. It feels cool and classical. Editor: We're looking at an image entitled "Borstbeeld van Asklepios" attributed to André Joseph Mécoun, created sometime between 1781 and 1837. Curator: Ah, Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine and healing. It’s fascinating how the artist chose to represent him in what appears to be a print. Given the period, that choice would be a factor in making this deity available to the common viewer. Editor: Exactly. Consider the process itself. It’s not just about the end image, but about the reproductive possibilities that printmaking offered. We see that echoed in the depiction of the marble itself—simultaneously showing off its carving and hinting to further possibilities of its representation. How does this marble form then become broadly accessible? Curator: Good point. It democratizes the image, spreading classical ideals of health and well-being more widely through society. Although the figure of Asclepius is of course male and racialized as white—and thus the imagery may not extend the benefits to the whole of society, especially given the legacy of enslavement. Editor: The tools! Look closer at the caduceus depicted on the base. Consider the production of scientific and medical instruments around that time, too. The print's not just circulating an image; it connects to the material conditions of health and knowledge production itself. Curator: I see your point. It creates a loop. But what also intrigues me is how the neo-classical style, popular at the time, would use such imagery to connect current power structures to a glorious, legitimizing past. Who had the means to engage with classical themes and their associations? Editor: The details of line, hatching, and paper are as integral as the symbolic subject represented. It makes you question assumptions about ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, because there's skilled craft involved, regardless of what that artistic establishment wanted to tell you. Curator: True. Considering the period when this was made, the distribution of prints would likely be reliant on colonial trade routes, also suggesting an unequal access depending on social stratifications within European culture. Editor: Looking at this piece makes you wonder what else was travelling those routes and what other kinds of knowledge the image left behind, and for whom it became powerful. Curator: Indeed. It shows how even seemingly straightforward classical depictions can reveal complex connections to power, production, and social access when we delve deeper. Editor: I’ll take it a step further and see in those same classical features a material that speaks loudly of all the work needed to shape it, and its accessibility and impact.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.