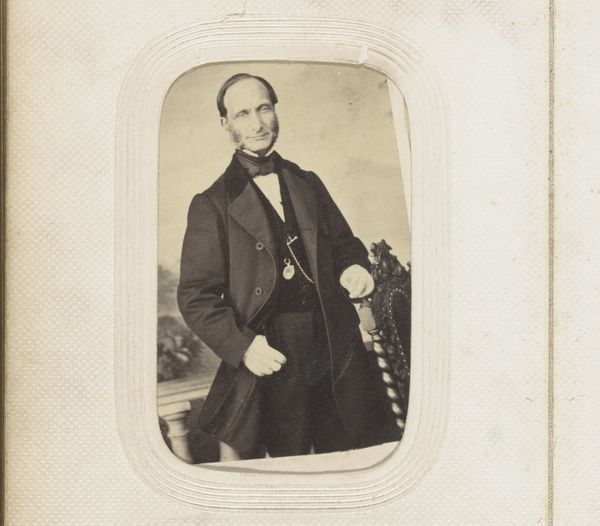

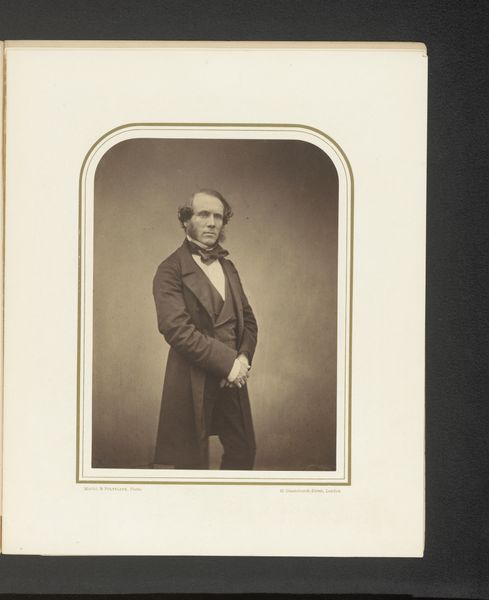

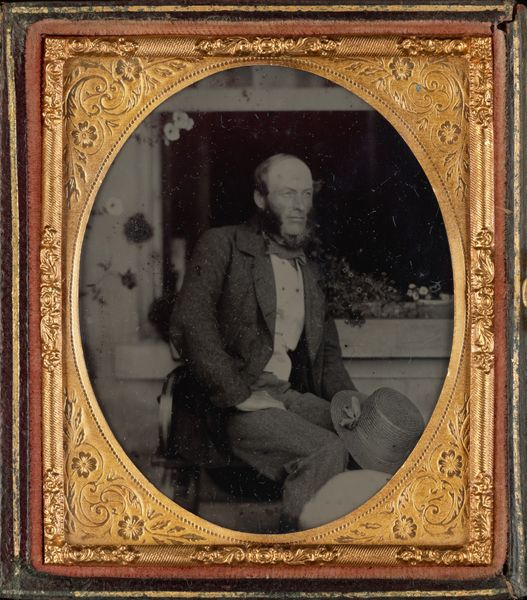

![[Portrait of a Man] by Mathew B. Brady](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2JmZGRlNWMwLTQ2MzktNDg4ZC1hMDdjLTRmYmE5ZWZhOTNiMi9iZmRkZTVjMC00NjM5LTQ4OGQtYTA3Yy00ZmJhOWVmYTkzYjJfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

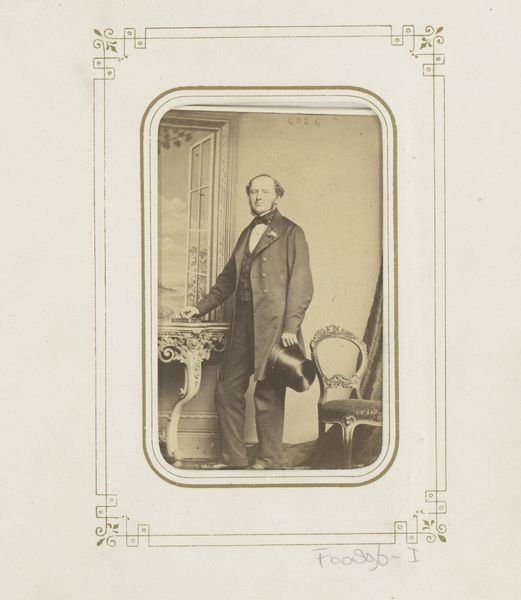

Dimensions: Mount: 11 3/16 in. × 9 1/8 in. (28.4 × 23.2 cm) Image: 9 15/16 × 7 9/16 in. (25.3 × 19.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

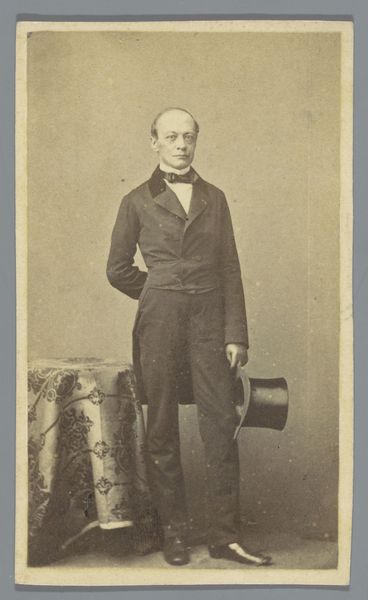

Editor: So, we have Mathew Brady’s "Portrait of a Man," likely from between 1855 and 1859, a daguerreotype—or maybe later, a gelatin silver print. The image's sepia tones give it an antique feel. What strikes me most is its inherent formality; it feels both composed and posed, like an artifact from a particular class. What aspects draw your attention? Curator: What interests me most is the material reality and production. Daguerreotypes, gelatin silver prints; the very choice of photography as a medium was deeply implicated in the expansion of industrial processes and their intersection with burgeoning consumer culture. Brady wasn't just capturing an image; he was participating in a changing world of production. Editor: I never considered it that way. Curator: Think of the process itself—the precise chemical reactions, the skilled labor required to create a single image. The sitter, presumably affluent enough to afford this new form of portraiture, also participates in the capitalist production. It democratizes portraiture yet it perpetuates the social hierarchies. Editor: Ah, so you're seeing the photograph as evidence of 19th-century capitalism at play. The making of a photograph being about so much more than just visual likeness. Curator: Precisely! Look at his attire. The cut and cloth signal his socioeconomic position, shaped by manufacturing capabilities and trade networks of the era. His dress connects to broader histories of textile production and consumption. This portrait isn't only of *him*, but also of the *system* he inhabits. How does it shift your perspective, now? Editor: It prompts questions about the labor conditions of that textile industry. And also it raises the fact of who had access to create these types of portraits. This piece goes beyond capturing a moment and, as you pointed out, embodies socio-economic dimensions through its medium, production and, yes, even the sitter’s presentation. Curator: Exactly. The photograph is no longer just a window to the past, but an artifact revealing complex industrial, labor and social conditions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.