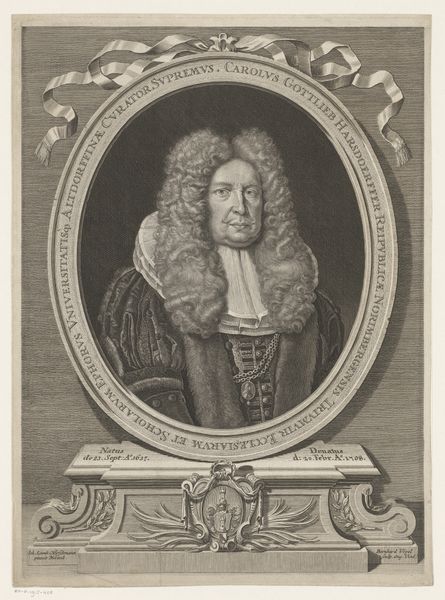

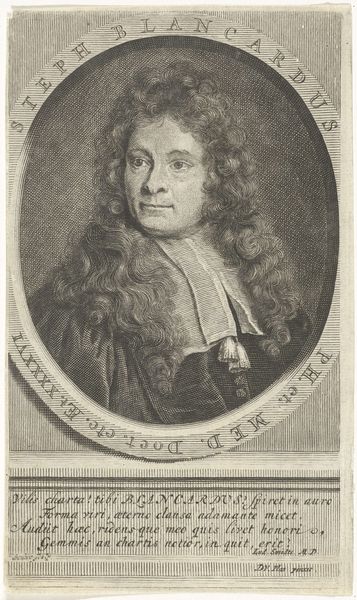

drawing, print, metal, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

metal

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 158 mm, width 93 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Tobias Laub's "Portret van Philipp Anton Laub" from 1744, a work rendered in engraving. It looks rather formal, and I am struck by how the print itself almost mimics the rigid structure of Baroque portraiture. How do you read this image? Curator: Consider the materiality. This isn't painting; it's engraving – a process involving skilled labor and mechanical reproduction. Look closely at the lines. They're not spontaneous gestures, but rather carefully incised into a metal plate, demanding precision. The "original" exists only as a matrix for endless copies. This challenges our conventional ideas about authorship and value, doesn't it? How does mass production change the value and audience of an artwork? Editor: That’s fascinating. It makes you think about who this portrait was *for*, and how readily available images were to those outside the upper class. Was printmaking viewed differently than painting at this time? Curator: Exactly! Printmaking allowed wider circulation, embedding this image in social networks. The inscription and Laub’s clerical attire, too, situate the print within specific cultural and religious contexts. Note the inscription's reference to enduring merit, achieved not through birth, but through intellect. What statement is being made here about achievement and status in this moment? Editor: I hadn’t considered how the method of production shaped the social purpose. The intellectual achievement through a repeatable artform! Thank you, I've certainly gained a richer understanding of this portrait and the impact of materiality. Curator: And I find myself considering anew the democratization of imagery within these elaborate Baroque conventions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.