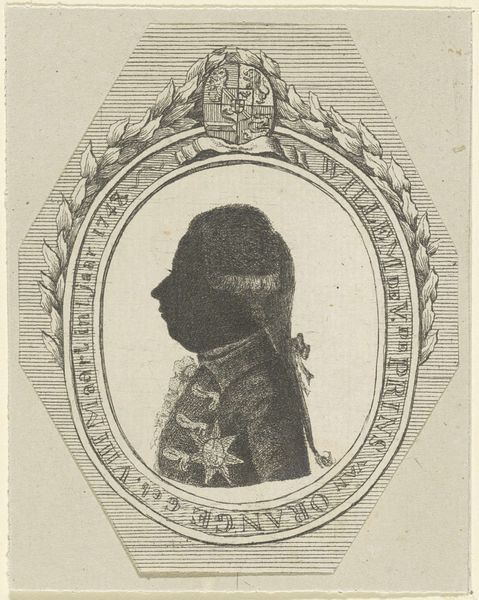

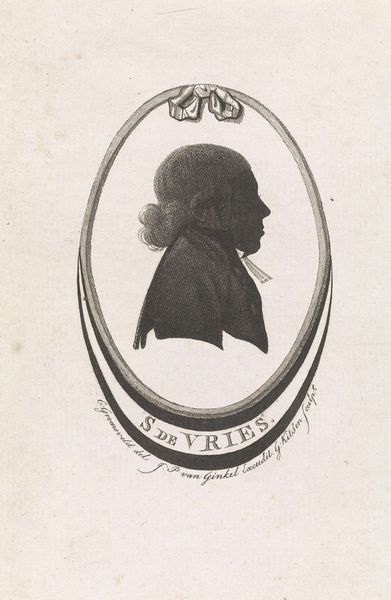

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

shading to add clarity

# print

#

form

#

pencil drawing

#

line

#

engraving

#

profile

Dimensions: height 94 mm, width 61 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a silhouette portrait of Dingeman Wouter Smits, dating somewhere between 1776 and 1810. It's an engraving, giving it a distinctly graphic quality. It almost feels…austere. What strikes you about this print? Curator: The silhouette itself speaks volumes about social status and the rise of the middle class. Silhouettes became incredibly popular as a more affordable alternative to painted portraits. Did everyone suddenly become interested in art? No, not exactly, but those with growing capital now have an entryway into artistic practice and production. Editor: So it’s about accessibility and participation? Curator: Precisely. This artwork democratized image-making, offering a means of self-representation for a broader public. Note the subject's elaborate wig; it signified profession and respectability. What message was the sitter intending to convey to the society? Editor: That he was someone of importance, fitting into established societal structures? Curator: Yes, it was a calculated display of identity. The very act of commissioning or acquiring a silhouette portrait became a participation in shaping one’s public image, and ultimately their social standing, that continues to fascinate scholars of art history today. Think of this artwork as part of larger narrative regarding artistic consumption! Editor: That's fascinating. I hadn't considered the implications beyond the visual representation itself. The silhouette now feels less austere and more like a statement. Thank you! Curator: Indeed, every artwork reflects larger social, political, and economic realities. It's often in considering these connections that an object truly starts to speak.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.