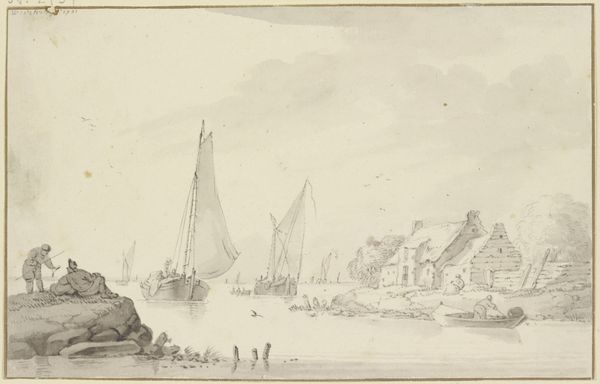

drawing, watercolor

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

river

#

charcoal drawing

#

watercolor

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

#

realism

Dimensions: height 191 mm, width 285 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Today, we're exploring Antonie Waldorp's "River View with a Sailing Ship," created sometime between 1813 and 1866, currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My initial impression is one of subdued tranquility. The soft, almost ethereal washes of color give the scene a hazy, dreamlike quality. You can almost feel the stillness of the water and the dampness in the air. Curator: Indeed. Waldorp captures a particularly Dutch sensibility, wouldn’t you agree? Think of the 19th-century context. This work emerges during a time when the Netherlands is redefining itself politically. Artists look to domestic landscapes as symbols of national identity and cultural pride. Editor: I’m struck by the process. You can almost see the artist at work, building the scene with layers of watercolour and pencil. Look at the rendering of the sails—they are transparent but still feel structurally sound. The making emphasizes utility; ships were fundamental for trade and a source of labor. Curator: The inclusion of the old building on the bank also points to Romantic notions of the past, adding a historical depth and a melancholic reflection on time passing. These buildings have meaning beyond architecture; the ruin gives history value. Editor: Exactly! The layering and materiality communicate time physically. The rough sketch style makes us think of immediacy, even necessity, for him to get this onto paper. The muted color palette adds a somber element. I wonder, what type of paper did Waldorp work on for the river view? What type of pigment creates the atmospheric perspective? These are material considerations as well as historical choices. Curator: These drawings remind us of the accessibility of art in a time of emerging public museums and galleries. Waldorp shows an idealized version of the local Dutch landscape, where industry meets culture. This depiction provided an aesthetic representation of Dutch values. Editor: It is a beautiful dance of water, pigment, and paper—of labor and land, reflecting a specific time and its people. I think examining what these illustrations do materially as cultural objects tells us much more about artistic practices and even the consumption of art for the growing Dutch middle class at the time. Curator: It certainly shifts our perspectives. Considering its position within broader societal trends and the means of artistic production reveals just how interwoven art and the world really are. Editor: Indeed, I’ll never look at a "simple" watercolor in quite the same way again.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.