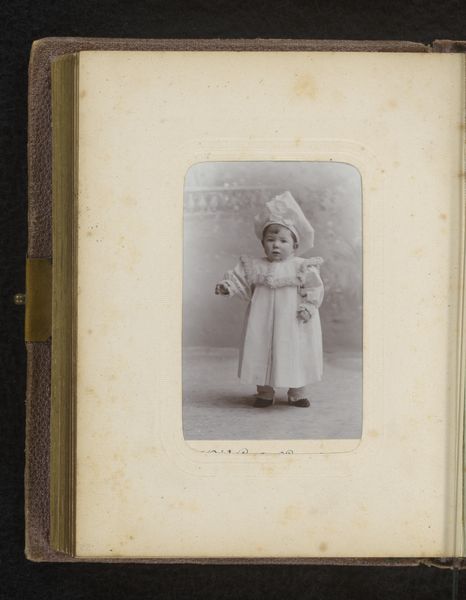

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

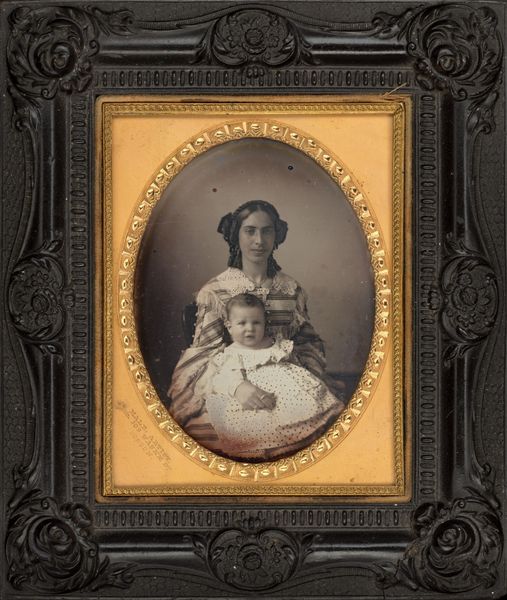

framed image

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 345 mm, width 303 mm, depth 19 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at "Portret van Cornelis Rooker," a gelatin-silver print dating from around 1905 to 1908 and housed at the Rijksmuseum, the overwhelming impression for me is one of rigidity. It's like a tightly wound clock. Editor: Indeed. Before us is more than just an image; it is a carefully constructed object of visual encoding. The photographer's deliberate choices in lighting and framing immediately come to my attention. Curator: Certainly, the framing is impossible to ignore. But the image itself seems less about the child, Cornelis, and more about projecting an ideal image of the family, perhaps even a commentary on social status, wouldn't you say? Editor: One might see it that way. However, let’s consider the visual language at play. The tight framing isolates the subject, creating a focal point. That severe truncation generates a fascinating sense of enclosure; all sightlines funnel attention straight into Cornelis’ solemn gaze. Curator: I concede it is compelling. Though considering the timeframe and photographic portraiture of this era, these types of portraits of infants were common ways for middle-class Dutch citizens to memorialize their family’s lineage and aspirations. The composition, though visually stark to a contemporary audience, might have conveyed aspirations and even pride. Editor: Aspirations yes, but not of a mere material type. There's a structural paradox here—the child's softness and implied vulnerability juxtaposed with the medium’s inherent harshness, resulting in visual friction. This clash begs us to investigate what the image fails to depict in tangible ways, namely the boy's hopes or dreams for the future. Curator: An intriguing point. I hadn’t considered it through the lens of absence and anticipation. Considering these photographs served to memorialize figures long after their passing, there could be social commentary and melancholy present, as you said. Editor: Precisely. The power resides not in its surface aesthetics but rather in its symbolic language; its visual poetics if you will. It invites one to explore both presence and what lingers unsaid within these lines of visual history. Curator: It's been a fascinating to delve into what's concealed beneath the photograph's placid surface. Editor: Indeed, examining how cultural imprints interact with these static images deepens our understanding of their complexity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.