drawing, paper, ink, architecture

#

drawing

#

paper

#

form

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

geometric

#

pen-ink sketch

#

line

#

pen work

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 297 mm, width 190 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

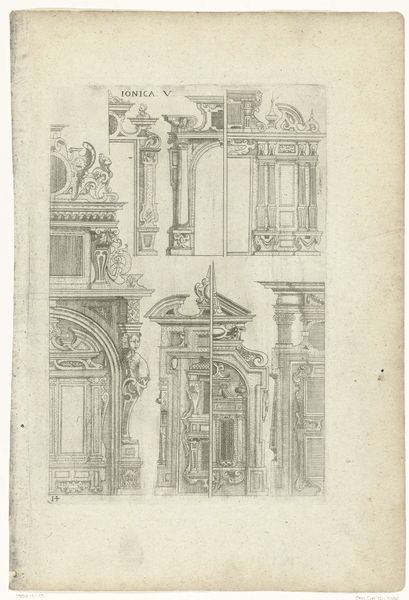

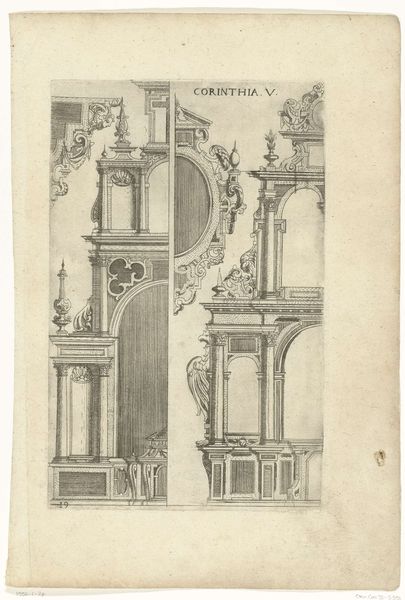

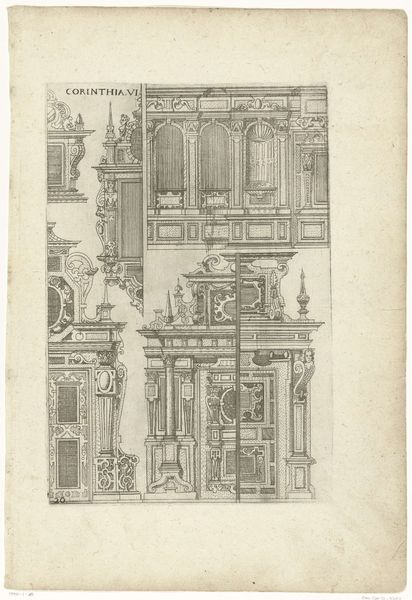

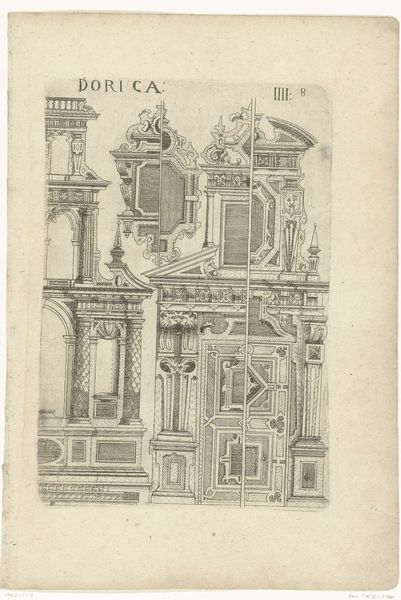

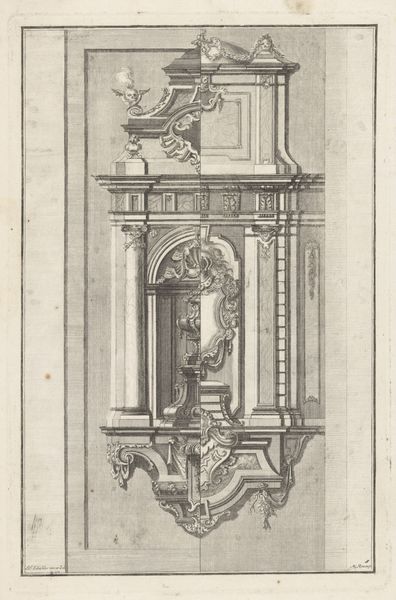

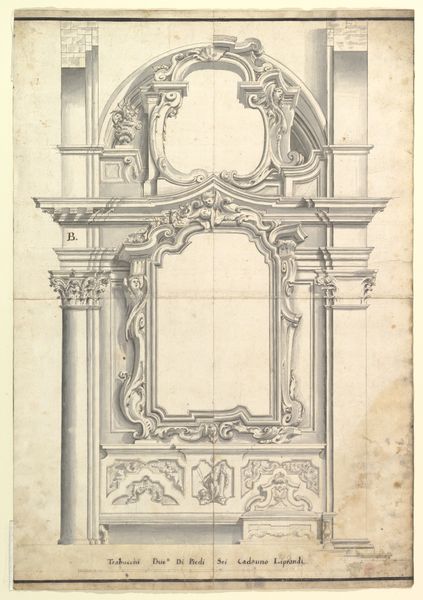

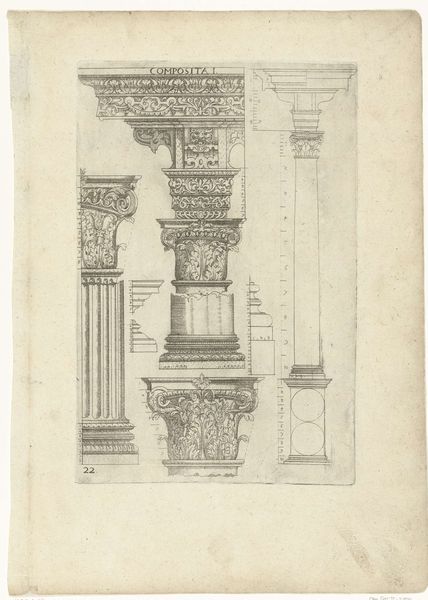

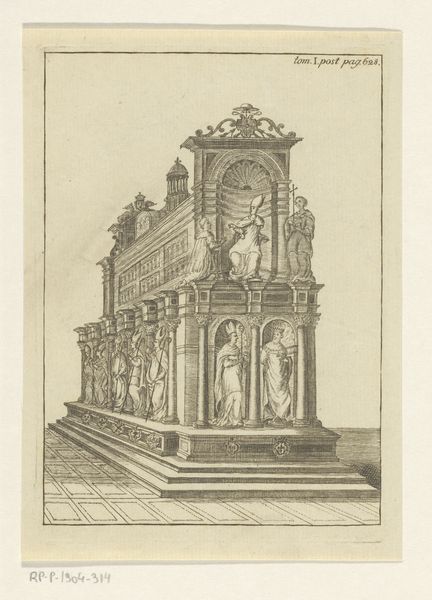

Curator: Looking at this ink drawing from 1610, “Drie halve epitafen en drie halve altaarconstructies,” which translates to "Three half epitaphs and three half altar constructions", I am immediately struck by its starkness. It's a study in potential, like a series of blueprints not yet realized. Editor: The paper bears the ghost of geometry. Look at how these sketched forms appear like a theater set designed to amplify voices for the afterlife. It lacks a body, flesh; merely line and skeletal design. It makes me consider the architecture of grief, of the performance surrounding mourning. Curator: It’s fascinating to consider this from the perspective of ritual and social construction, as the physical altar, and thus the performance of ritual, is itself the making of space and, furthermore, the staging of social hierarchy and identity. The careful depiction of ornamentation becomes evidence. Editor: It’s so clinical, almost devoid of feeling. The production seems more focused on architectural possibility than any true emotive outpouring. But let’s consider the production: paper, ink, the hand. This piece serves as both concept and record of the planning stages involved in crafting structures dedicated to memory. Curator: Agreed. The ephemerality of ink on paper against the imposing idea of a monumental structure underscores a dialogue on permanence versus change. Also, considering who may have commissioned such a study? How does their social position influence our reading of the work? Did they wield political or religious power? Editor: Thinking about those commissioned by powerful influencers certainly is relevant, yet how this image persists on the page seems more a catalog of pattern and making—production by artisans, bricklayers. This drawing showcases a confluence of design choices but perhaps never manifested fully in built form, its truest form of materiality on the paper, as a ghostly suggestion. Curator: Exactly. In its incomplete, skeletal form, it gestures towards how symbols of status and religious power are physically erected but also imagined, questioned, and, here, perhaps left in a state of suspension. The artist invites us to reflect on who ultimately benefits from these structures. Editor: Indeed, these fragile yet permanent lines invite us to inspect the handiwork needed for altars and epitaphs that serve not only a divine purpose but more fully a record of the materials, the craftspeople, that persist as a function of design on a flat sheet. The physical work recorded now seems very alive still.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.