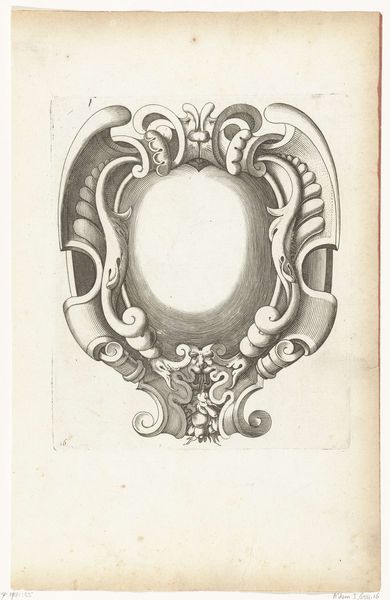

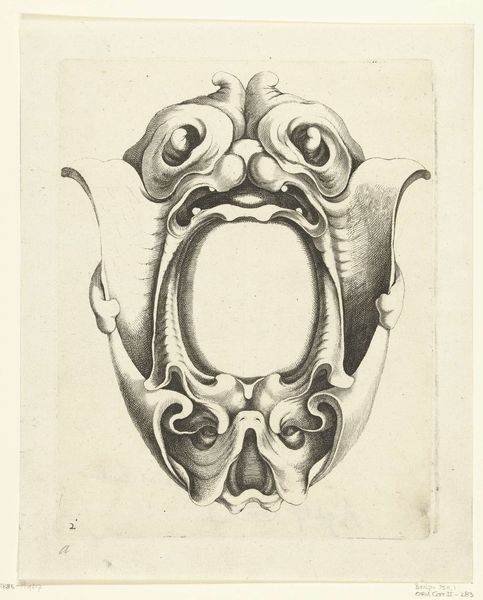

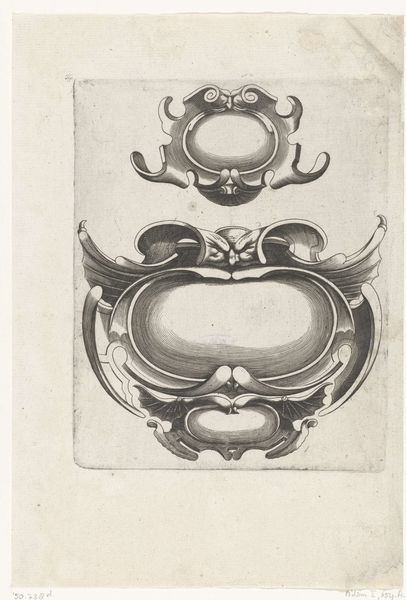

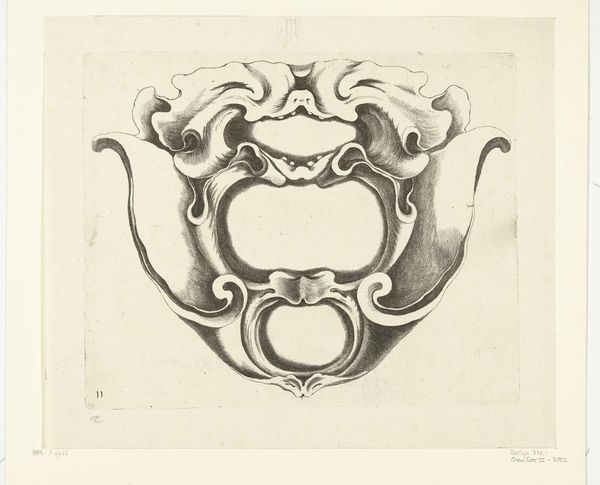

drawing, intaglio, engraving

#

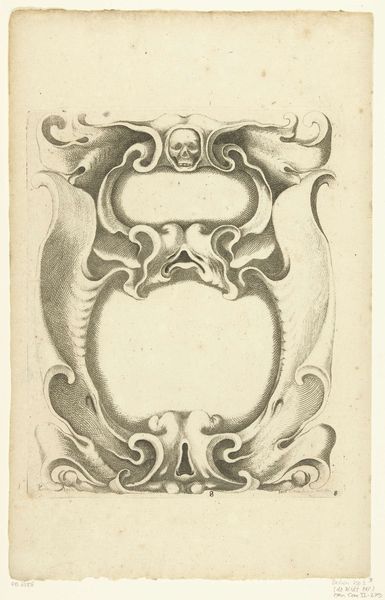

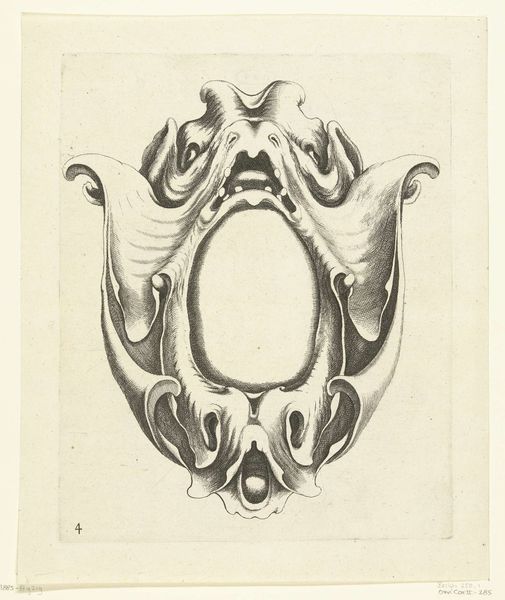

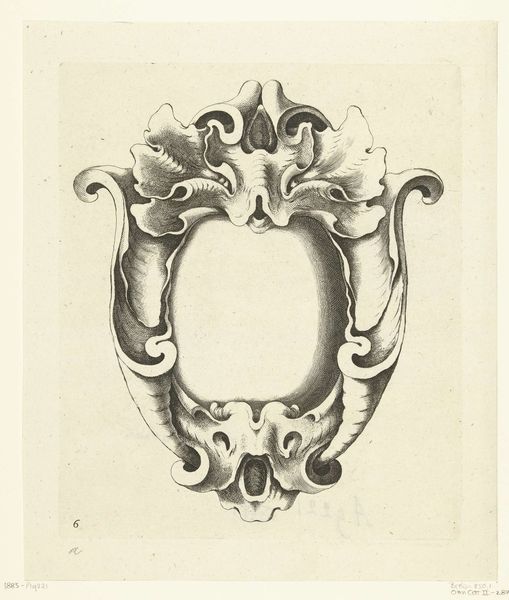

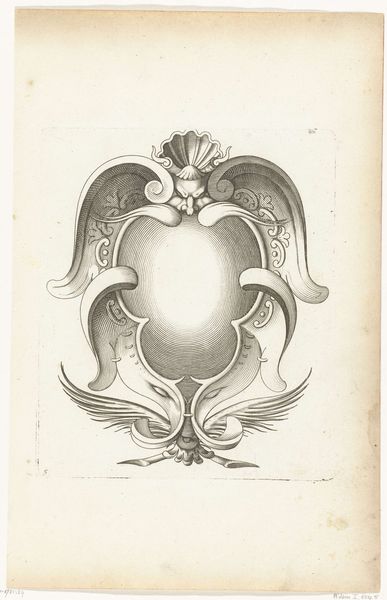

drawing

#

pen illustration

#

intaglio

#

form

#

geometric

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 223 mm, width 180 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: We're looking at Jacob Lutma’s "Cartouche with a large monster head," made around 1654 to 1678, using engraving. The intricate lines forming this symmetrical, somewhat grotesque frame, really strike me. What do you see when you look at it? Curator: What interests me most is the *process* behind this image. Lutma, as an engraver, meticulously manipulated materials – copper, acid, ink – to create this very object. He didn't just represent an idea; he actively labored with materiality to create a printing plate and a subsequent visual artifact. Editor: That’s an interesting way to think about it. I hadn't really considered the labour involved so much, but I can see what you're getting at. It does seem very meticulous. Curator: Exactly! Consider also how prints like these would function within the broader culture of the 17th century. What societal purposes might prints such as these serve beyond mere decoration? Might they function as models? Editor: Maybe. It looks like it could be a design template or perhaps part of a catalogue of some kind for craftspeople. Almost like pre-fabricated artistic labour. Curator: Precisely! By focusing on Lutma's labor, on the material and how prints were manufactured, distributed, and *consumed*, we can connect this single image to the larger economic and social realities of his time. How does the consideration of materials, engraving, and the social impact of this form re-shape how you interpret it? Editor: It transforms my perspective completely! Seeing it now as a tangible artifact, a product of its time and labor rather than simply as an image, reveals an unexpected depth of understanding. Curator: Absolutely, examining art this way invites new ways to understand artistic production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.