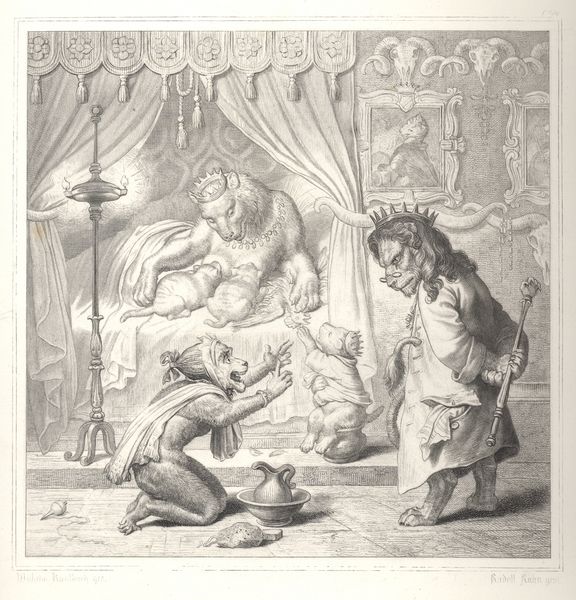

Death of the Firstborn, from "Dalziels' Bible Gallery" 1865 - 1881

drawing, print, woodcut, engraving

drawing

medieval

narrative-art

death

figuration

woodcut

men

line

history-painting

engraving

columned text

Dimensions: Image: 7 9/16 × 6 7/8 in. (19.2 × 17.4 cm) India sheet: 9 3/4 × 8 3/4 in. (24.7 × 22.2 cm) Mount: 16 7/16 in. × 12 15/16 in. (41.8 × 32.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: "Death of the Firstborn" from "Dalziels' Bible Gallery," dating between 1865 and 1881. It’s a compelling woodcut engraving after a design by Frederic Leighton. Editor: The grief just leaps out at you. Look at the figures— the agony is palpable. The stark blacks and whites amplify the despair. Curator: Absolutely. The image powerfully depicts the tenth plague of Egypt from the Book of Exodus, where the firstborn of every Egyptian family died. It's a history painting that evokes an Old Testament narrative through striking figuration. Leighton originally designed these biblical scenes with mass consumption in mind, with woodcut engraving allowing for cheap, relatively accurate, replication. Editor: Cheap maybe, but think about who benefits and who suffers here. This imagery really perpetuated certain colonial views of non-Western people suffering under Biblical-driven judgment, something deeply ingrained in Western society back then. It is problematic, I find, how easily religious justifications are wielded to excuse inequality and tragedy. Curator: True, and Leighton would certainly have had a largely Christian audience that perhaps didn't recognise any possible prejudice here. But think about the sheer artistic talent in generating so much drama. Note Leighton’s expert manipulation of light and shadow. The emphasis on the lifeless body of the young man... Editor: It's striking how central the male nude is to this biblical scene. You wonder why Leighton framed suffering through a male perspective— patriarchal narratives shaping whose pain matters in historical representation and cultural memory? The details, like the water pitcher or patterned base border, seem like background noise compared to the man’s limp body. Curator: Interesting that you say that, as Leighton’s choice of details actually brings a particular period authenticity and sophistication, particularly during that era of historicism in Victorian art and design. Editor: This makes me consider the complex dance between aesthetics and ethics. A beautiful piece doesn’t automatically get a free pass, does it? And isn’t it the role of art to make us uncomfortable sometimes? Curator: Absolutely. These are potent reminders of past suffering, which make them important. Thanks for bringing that additional layer to the artwork, that for some, these scenes do not prompt reflection but actually serve as evidence to old assumptions. Editor: Thanks, I’m glad you considered what I was suggesting. Examining art in this light keeps the conversations relevant and helps uncover those untold perspectives, doesn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.