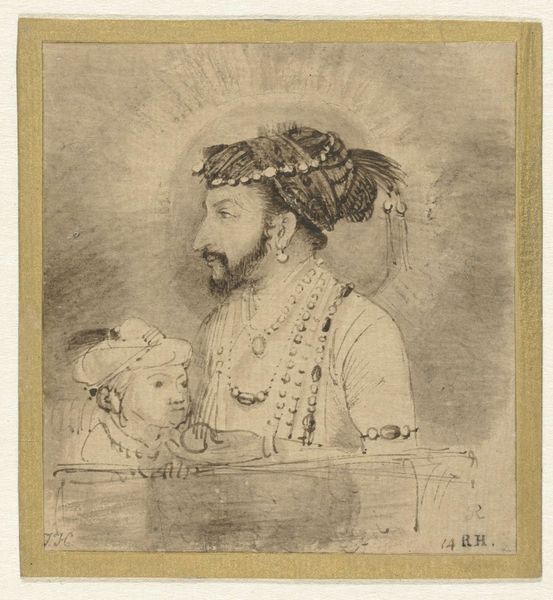

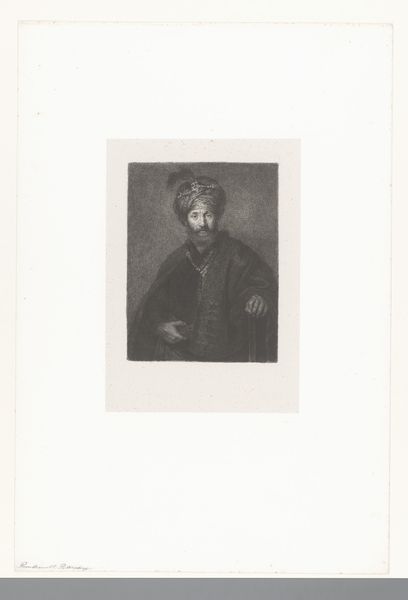

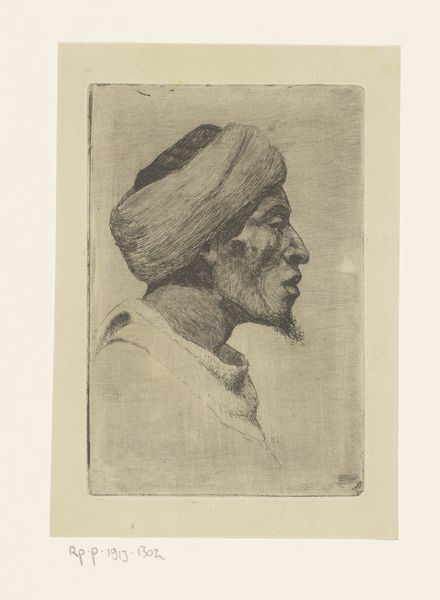

drawing, paper, ink, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

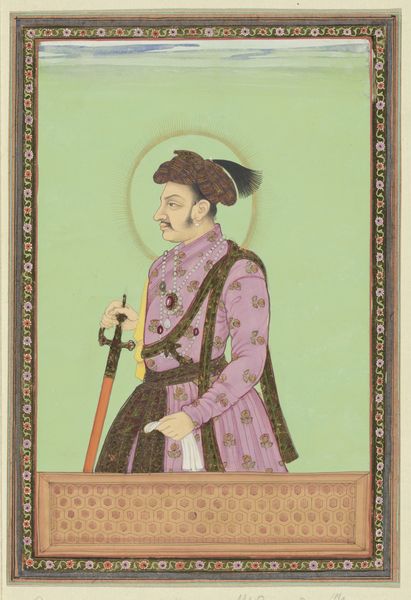

asian-art

#

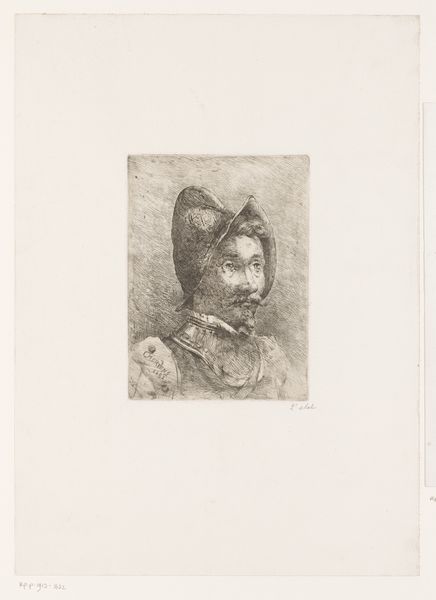

charcoal drawing

#

paper

#

ink

#

pencil drawing

#

line

#

portrait drawing

#

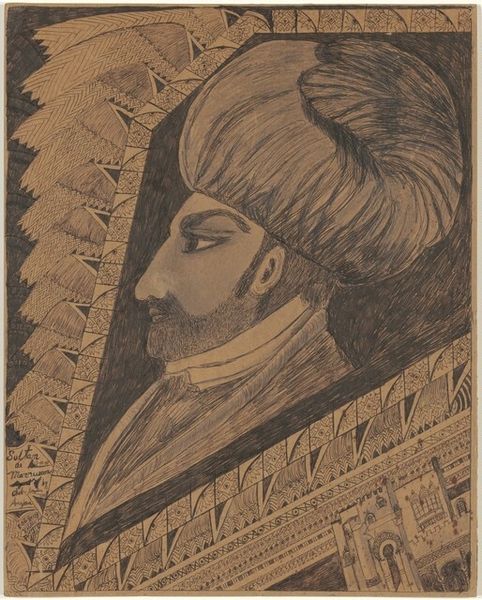

islamic-art

#

charcoal

#

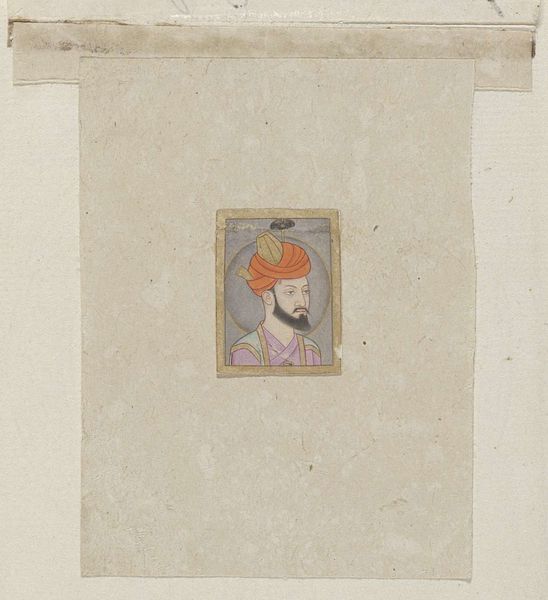

miniature

Dimensions: height 69 mm, width 71 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a drawing of Shah Jahan, dating back to about 1656-1658, made with ink and charcoal on paper by Rembrandt van Rijn. There’s a quiet intimacy to it. What do you see in this piece, especially considering Rembrandt’s identity as a European artist depicting an Asian ruler? Curator: It’s fascinating, isn’t it? On the surface, we see Rembrandt, a Western artist, engaging with the image of an Eastern emperor, Shah Jahan. But I think it runs deeper than that. How does the drawing participate in a longer history of Orientalism? What does it mean for Rembrandt, working in the Dutch Golden Age, to be looking at Mughal art, even copying it? Editor: That’s a great point. Was he critiquing or admiring the subject? Curator: Perhaps both. We need to consider the social and political context of the Dutch Republic, their global trade, and the burgeoning field of ethnography. Rembrandt likely never met Shah Jahan, and the power dynamic embedded in this representation needs unpacking. Does he humanize him or exoticize him? What do the fine lines tell us about how Rembrandt viewed the emperor's status? Editor: So it’s not just a portrait but a commentary on cultural exchange and power, even unintentionally? Curator: Precisely. The artistic choices - the materials, the style – they all contribute to this narrative. And remember, history is never neutral. By engaging with the image of Shah Jahan, Rembrandt also defines himself, and, more broadly, Europe's relationship to the rest of the world. This isn’t merely an exercise in draftsmanship, it’s a political statement about cross cultural dynamics. Editor: That’s really eye-opening! It makes me see the piece in a totally different light. Curator: Exactly! This work reminds us to interrogate whose stories are told, by whom, and for what purposes. The conversation starts with what we see but doesn’t end there.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.