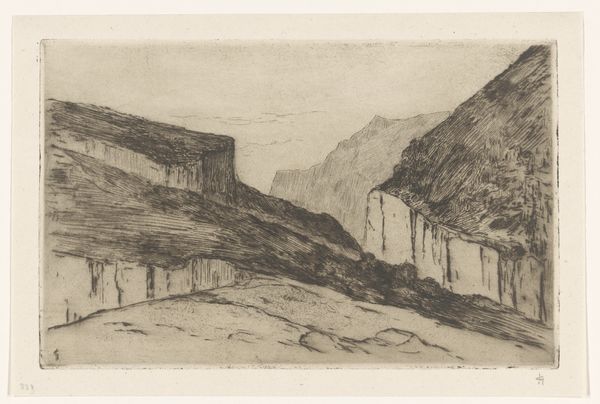

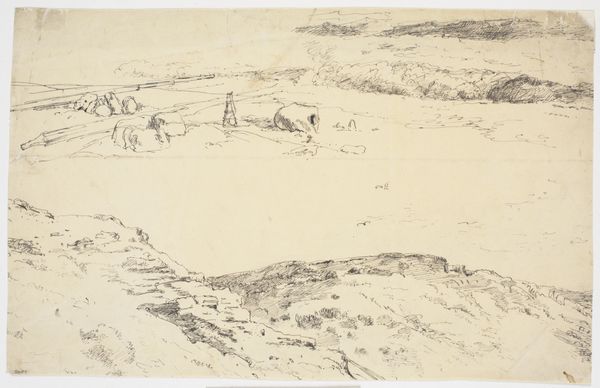

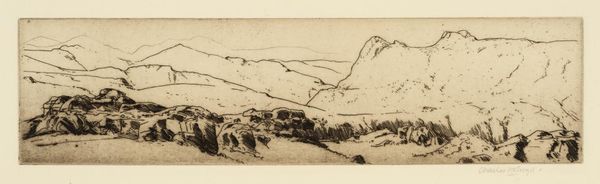

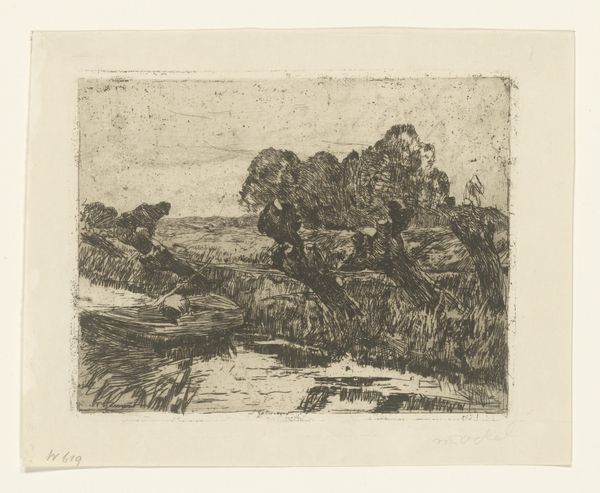

drawing, print, etching

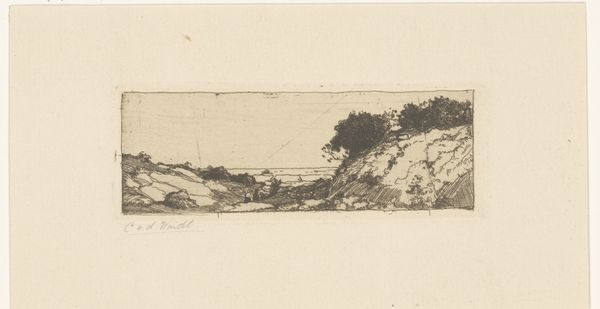

#

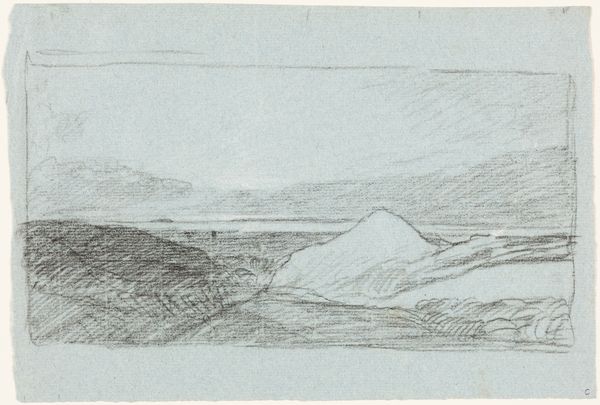

drawing

#

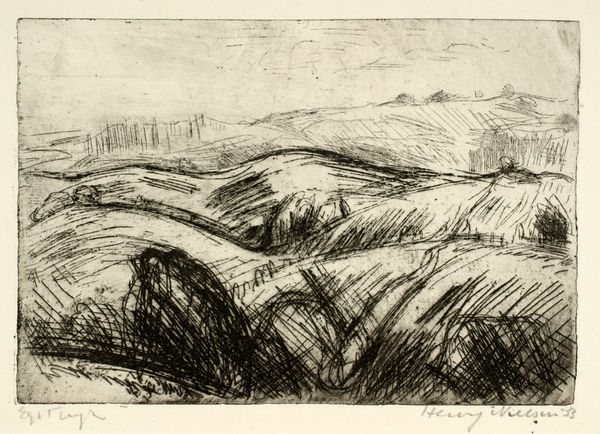

ink drawing

# print

#

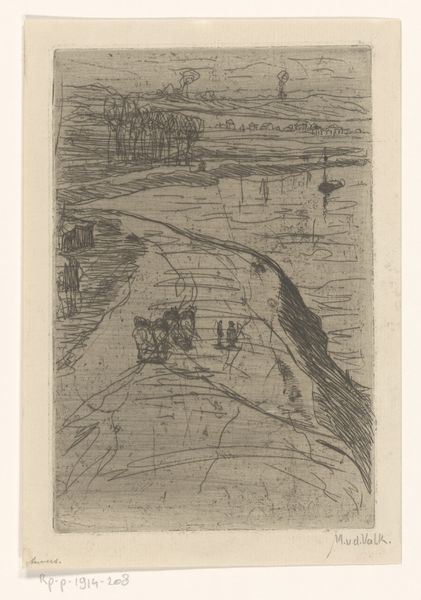

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

geometric

#

line

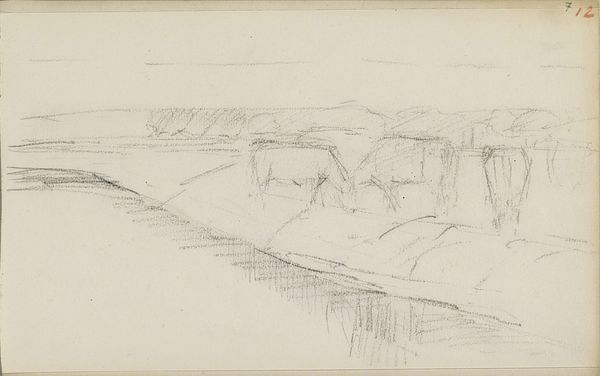

Dimensions: height 370 mm, width 430 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Wijnand Otto Jan Nieuwenkamp’s etching, "Constantine," possibly from 1911. It’s a landscape, with a village nestled near some cliffs. The rendering is so detailed it reminds me of topographical maps, with carefully placed lines to give the sense of form. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a powerful representation of the artist's relationship with the land. The title “Constantine” likely references the Algerian city, which, given the colonial context of the early 20th century, adds a layer of complexity. What narratives are being told, or perhaps silenced, by this landscape? Editor: That's interesting. I hadn't considered the colonial aspect. I was just admiring the details, how the lines create so many different textures. Curator: Look at the deliberate rendering of the built environment in relation to the natural forms, such as cliffs and agricultural fields. Who has the right to extract from, and define, this land? How does the act of meticulously depicting it further implicate the artist in this dynamic? Does the artist celebrate or question the existing relationship? Editor: I guess I see both. There’s reverence in the technique, in the way he painstakingly etches each line. But the colonial reading adds a sense of unease, of imposing a Western gaze on a place. Curator: Precisely. Think about how landscape art often functioned as a tool of empire, visually laying claim to territory. How can we decolonize our view of this seemingly benign scene? Editor: This makes me realize how crucial it is to consider the historical context and cultural dynamics behind landscape art! It really opens up new ways to interpret a work that, on the surface, just seems like a beautiful view. Curator: Exactly! And it challenges us to continuously interrogate the power structures embedded in even the most seemingly simple images.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.