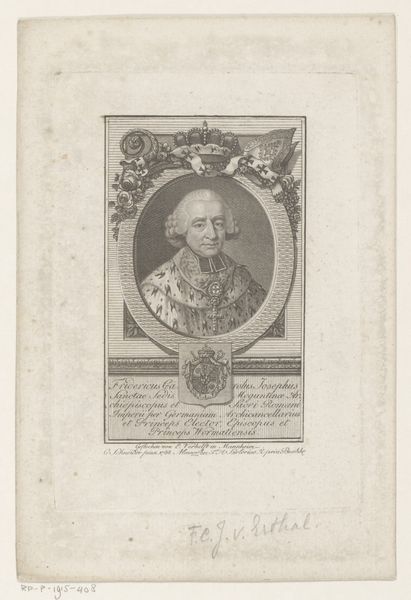

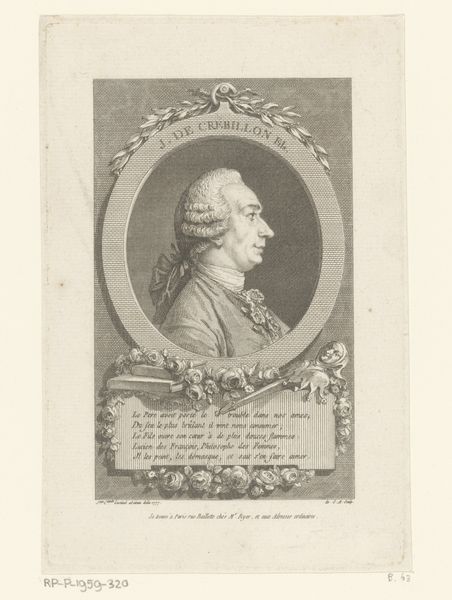

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 240 mm, width 172 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a rather formal print, a 1743 engraving by Georg Friedrich Schmidt, titled "Portret van Frederik de Grote", housed right here in the Rijksmuseum. I’m struck by the level of detail achievable through engraving, especially in rendering the armor and the lace. How should we interpret a piece like this, focusing on materials? Curator: Let's think about the socioeconomic context in which this print was made. Engravings like this were reproducible, creating an illusion of accessibility to images of power. But, access to them also relied on disposable income. This artwork speaks to both the consolidation and the dissemination of power through the control of materials and processes, it relies on access and commerce to communicate its subject’s wealth and military dominance. What do you think about the choice of engraving instead of painting for a royal portrait? Editor: I suppose a print makes the image far more portable and replicable. Was it unusual to represent royalty this way? Curator: Not at all. Consider the division of labor required. Schmidt wasn't just an artist, he was also a craftsman embedded in a network of publishers and distributors. The king may not have physically posed in front of Schmidt but gave his authorization of the distribution of his image. These images functioned as commodities. The circulation of these prints created value for all people in the chain of production: the artist, publisher, distributor, and monarch, obviously. Editor: That makes me consider the actual labour behind making something like this, less focused on this specific figure and more about how prints generally affected artistic creation. Thanks, that perspective makes this portrait much more grounded. Curator: Exactly. Thinking about the 'how' and the 'who' of artmaking gives us a fuller understanding of the 'why'. It invites questioning established values, to investigate materiality, and celebrate craftsmanship.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.