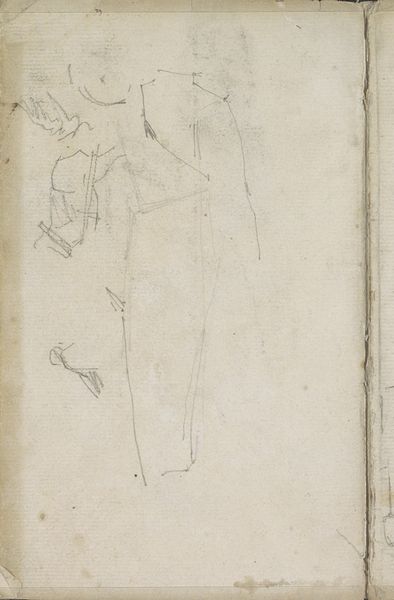

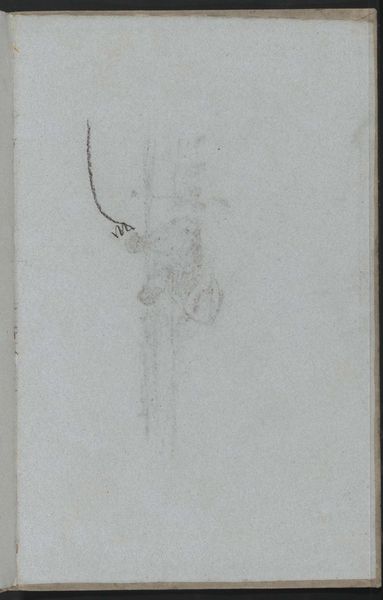

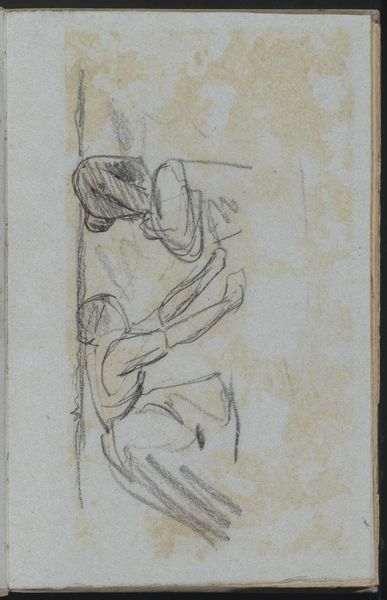

drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

impressionism

#

paper

#

pencil

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This drawing by George Hendrik Breitner, made between 1880 and 1882, is titled "Staand vrouwelijk naakt"—Standing Female Nude. Editor: There’s a tentative, almost hesitant quality to the lines. The sketchiness gives the figure a sense of vulnerability and transience. Curator: It’s a pencil drawing on paper, very much in keeping with the realist and impressionist styles he moved between. The quick lines convey a sense of immediacy. We can practically see the artist capturing a fleeting moment. Editor: Fleeting, yes, but within the established gaze. Even in its incompleteness, it reflects a specific power dynamic of artist and model, of observer and observed, a prevalent theme during that era when female bodies were so often rendered passively in art. Curator: It’s also interesting to consider that these nude studies were commonplace in academic training. But with Breitner's later, more documentary photographs of Amsterdam prostitutes, one sees a continuation of this engagement with representing the female form. Editor: The sketch seems almost dreamlike in its lack of concrete detail. It raises questions about the role of art in representing women and their experiences beyond the visual surface. What kind of social conditions made this possible? The female nude, while commonplace, was rarely represented by women artists, further solidifying that gaze. Curator: We could look at how Breitner utilizes light and shadow, even in these nascent strokes, to create a three-dimensional presence on a two-dimensional surface. There’s a long tradition of using drawing as a foundation for further art exploration, a testing of boundaries of form and space. Editor: And within that testing of form, it’s crucial to confront how these visual languages have historically codified and often objectified female bodies within societal structures and how our appreciation today requires us to stay ever vigilant. Curator: Yes. Examining this sketch alongside Breitner's other works helps us unpack the historical and cultural forces at play during the late 19th century, as well as acknowledge the work's echoes into contemporary modes of seeing and understanding gender and identity. Editor: Precisely. Understanding art isn’t just about appreciating what we see, but critically questioning the circumstances of how and why we are seeing it in the first place.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.