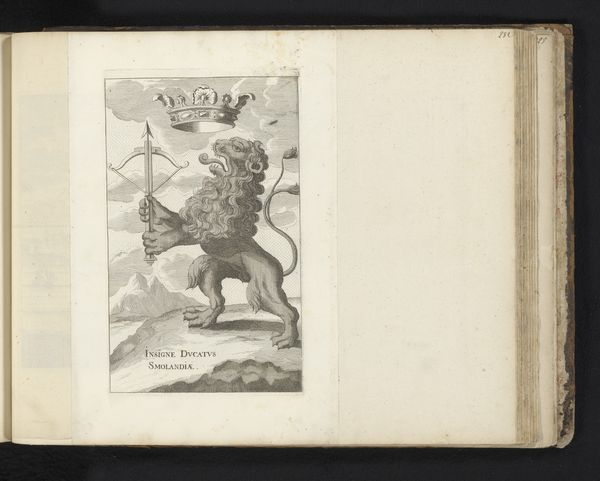

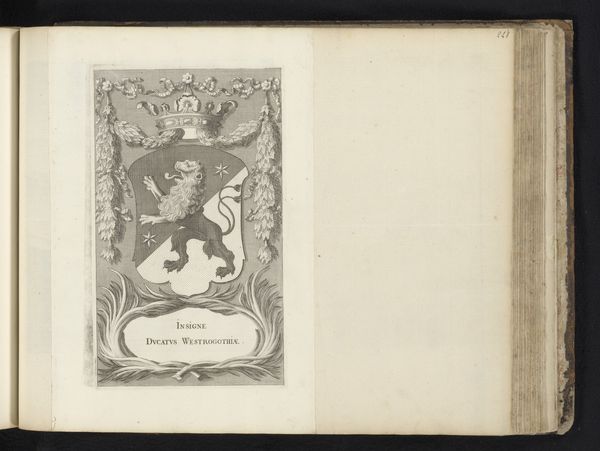

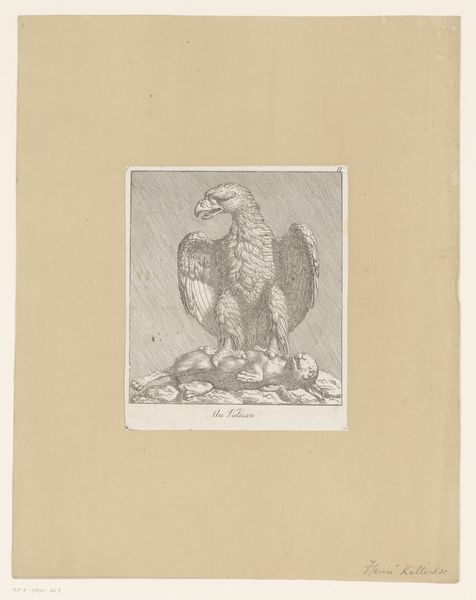

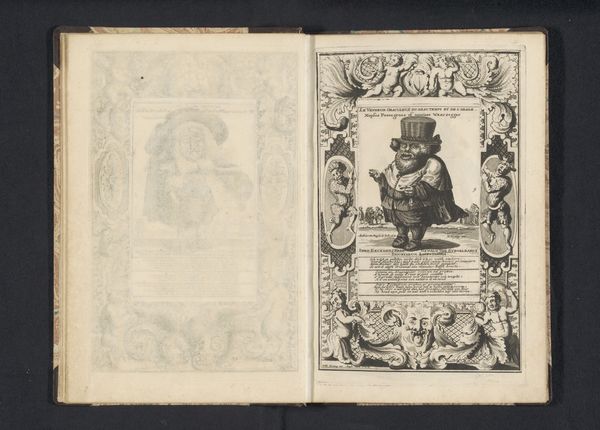

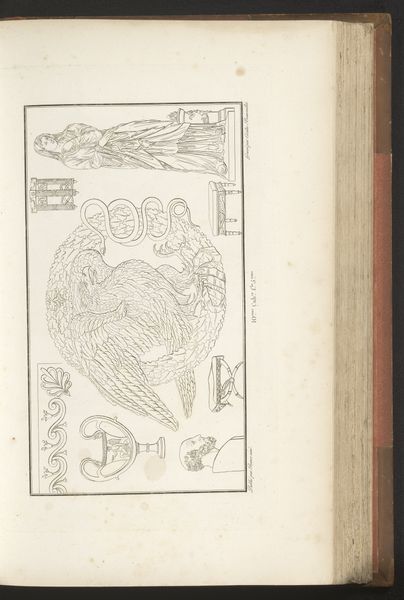

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

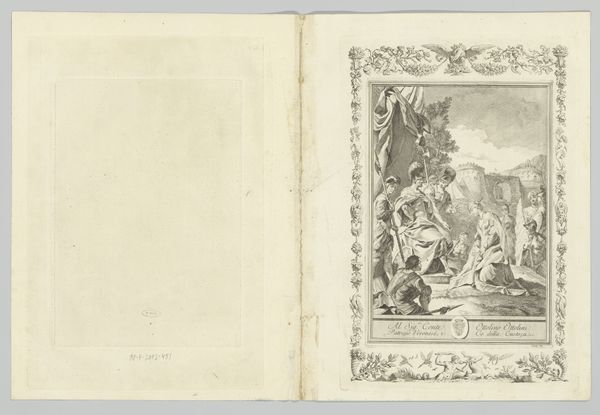

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 250 mm, width 150 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a baroque engraving dating back to 1696, titled "Wapen van Värmland," created by an anonymous artist. It features a heraldic symbol for the Swedish province of Värmland. Editor: It strikes me as stark and almost aggressive, really. That griffin dominates the space. The engraving’s lines are quite sharp; I imagine the process involved a lot of precise work to achieve such a crisp image. Curator: Absolutely. These types of images were powerful tools in asserting regional identities. Notice the crown perched precariously above the griffin's head; a very deliberate signifier of status and jurisdiction in late 17th-century Sweden. It was an era of consolidating power, after all. Editor: The material element really interests me: this image would likely have been reproduced widely, yes? Meant for dissemination. Considering the engraver, were they a part of a large workshop perhaps? What sort of labor went into something that feels simultaneously handcrafted and reproducible? Curator: That’s precisely the right question to ask. Printmaking was exploding then, impacting social mobility through increased accessibility. Prints like this were indeed made for circulation, often commissioned by civic authorities and disseminated amongst its elites as a display of influence. Editor: The paper itself also carries weight – what grades or quality would be acceptable for a coat-of-arms such as this? Does the specific quality influence its reception and perceived prestige? Curator: The quality of the paper was certainly indicative of its intended audience and the message it meant to convey. Better quality paper, hand laid and watermarked, added a degree of sophistication. However, simpler prints made on cheaper materials had a different sort of populist appeal. Editor: Seeing the inscription scroll below reminds us that graphic representations were also meant to be viewed as carefully constructed text—to be “read” properly according to symbolic systems—rather than transparently or passively observed as a likeness. Curator: Precisely. Allegory and heraldry relied on viewers understanding the encoded meanings and recognizing those markers of status and control. An image like this had layers of significance for a 17th-century audience deeply attuned to those visual cues of power. Editor: Thinking about its afterlife, what happens to these images when their political context recedes? Does this particular griffin morph into something more mythical over time? Curator: Good point. Over centuries, an image once politically charged, does become re-imagined within a broader cultural memory— perhaps losing its pointed specificity, becoming more of an icon representing something else. Editor: The focus on method and circulation really gives me new appreciation for what images meant and did within these societies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.