Dimensions: 15 1/16 × 22 13/16 in. (38.26 × 57.94 cm) (image)47 7/8 × 28 9/16 in. (121.6 × 72.55 cm) (mount, without roller)

Copyright: Public Domain

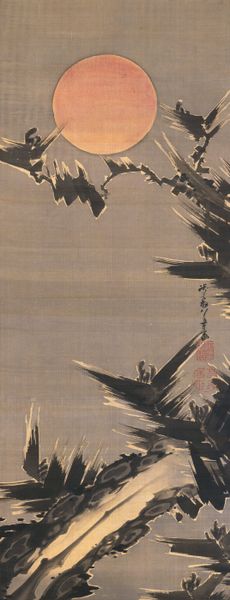

Curator: So here we have Wagtails, a lovely ink-on-paper drawing attributed to Kenkō Shōkei, dating back to the early 16th century. It’s part of the collection here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: It’s striking. There’s an immediacy in the gesture, the lean of the bird—almost like a snapshot capturing a fleeting moment in nature. Curator: Exactly! And Shōkei was working within a rich tradition of ink painting. The imagery, and especially this focus on birds in their natural habitat, becomes particularly popular through the Muromachi period in Japan, where you see artists really trying to engage with Chan Buddhism, Zen Buddhism. Editor: The restraint is palpable. Note the economy of line, the reduction of detail to imply form and texture. It’s far from a photographic representation. How would you connect the piece to Zen practices? Curator: Chan/Zen Buddhism is really about this notion of seeing things in their suchness, appreciating the sort of ready-madeness of the world around us. The literati culture flourishing at the time often associated such depictions with withdrawal from public life. They're interested in cultivating an image, quite literally, of being removed from the struggles of public office. Editor: The use of negative space is brilliant, wouldn’t you agree? The bird, the branch, are rendered with such delicate precision. And how it lets the tan color of the aging paper become another compositional element. Curator: Definitely. That blankness isn’t merely an absence of content, but it serves to focus our attention. This wasn't simply about skill in representation, but about conveying an idea, expressing a sentiment. We could even venture that this "absence" underscores that central Zen idea: emptiness. Editor: It's a powerful assertion about how much visual information we actually need, or require, to create meaning. I'm also struck how current this image is – the economy and balance would work very well for contemporary illustration. Curator: I think that speaks to its enduring power as a historical document but as a testament to what can be achieved through keen observation of our surroundings.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

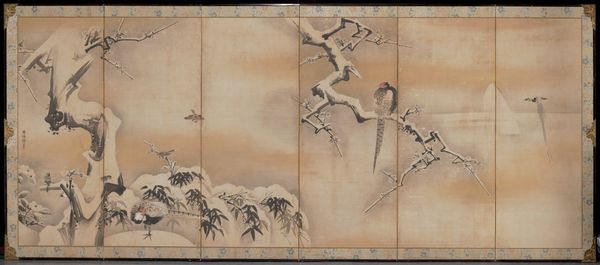

Kenkō Shōkei was both a Zen priest and a highly skilled ink painter who spent most of his career at the major Zen monastery Kenchōji in the city of Kamakura. Here he depicted a pair of wagtails on branches in strikingly contrasting poses. One stares down to the right as if aiming at some prey, while the other stands straight with a glance to the left. Shōkei painted his birds using a rapid brush technique called “boneless” (that is, without outlines), a method seen as particularly suitable for Zen themes. This combination of compositional device and technique suggests that these wagtails once flanked a third painting of a Zen deity or patriarch as part of a devotional triptych. Pictures of birds or flowers often served this purpose in Zen painting. But Shōkei’s original format seems to have been radically transformed by some later owner. Not only is the central painting missing but the vertical seams on each painting suggest that a previous owner cut up the original paintings to create two large horizontal compositions. The new format was less suitable for a Zen temple but fit the wide display alcove typical of grand residences. This type of conversion of a once sacred image to a secular one was not uncommon in Japan after the 1500s.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.