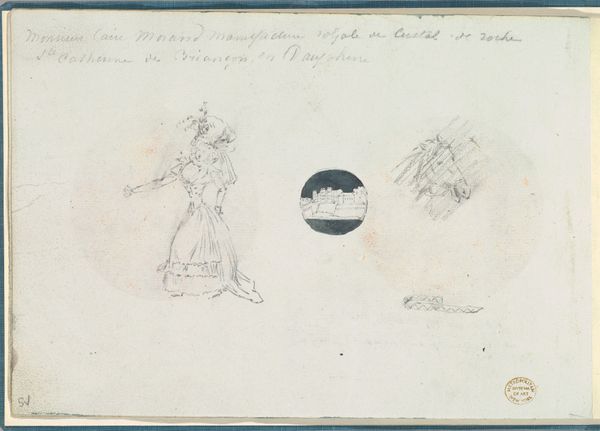

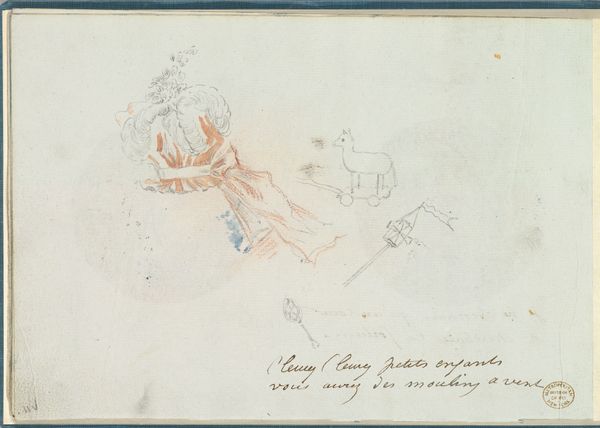

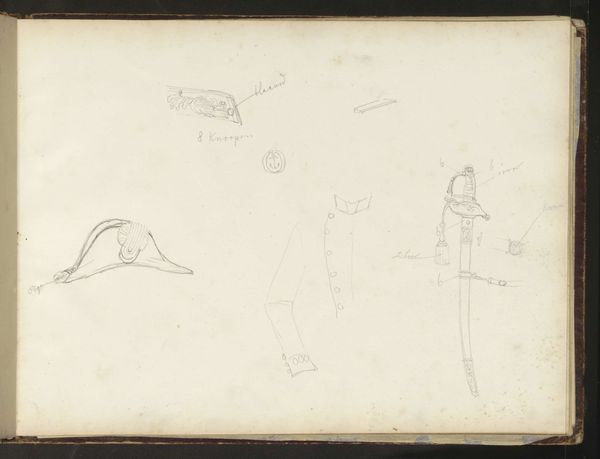

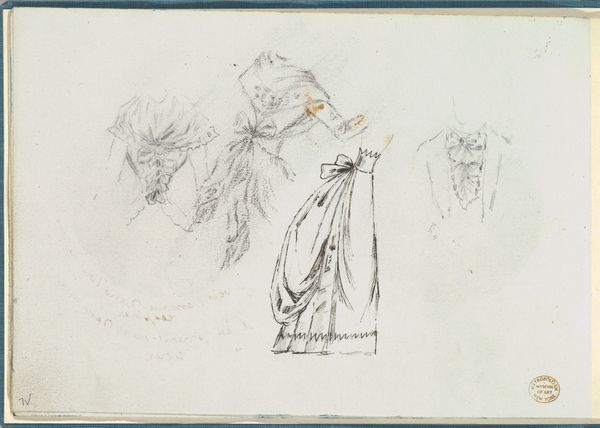

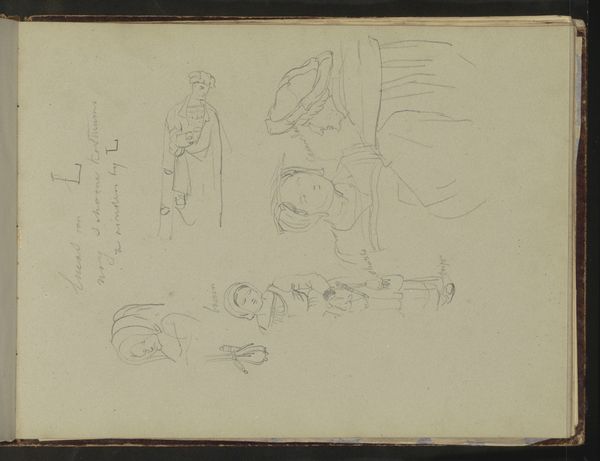

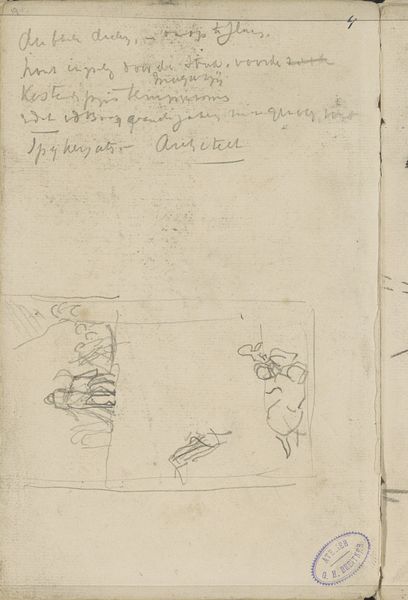

Three Costume Sketches of a Bonnet, a Cloak, and a Hat 1785 - 1790

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclassicism

#

paper

#

pencil

#

costume

#

history-painting

Dimensions: Sheet: 6 11/16 x 9 15/16 in. (17 x 25.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have "Three Costume Sketches of a Bonnet, a Cloak, and a Hat," dating from 1785 to 1790. It's an anonymous drawing rendered in pencil on paper, and the wispy linework gives it an ethereal quality. What do you notice about the way these forms are rendered? Curator: The almost clinical quality of the lines is striking; the sketches seem less concerned with conveying volume and more dedicated to defining shape. Note, too, how the negative space activates each costume, giving the set an airy feel, despite its neoclassical subject matter. It’s as though the garments possess their own latent movement. Editor: Do you think the artist was going for objective representation over subjective expression? Curator: That's a productive way to look at it. These forms have a deliberate air of detachment. The artist avoids sentimentality. We see function and shape—the platonic ideal of "cloakness" and "hatness"— not the emotional or social narratives a Romantic might pursue. Consider how the lack of shading flattens the image, focusing our attention on the relationship between lines and form. What effect does this have on the work's overall meaning? Editor: It does lend a certain precision, a focus on the architectural aspect of clothing almost. So the sketches become about the abstract shapes of garments more than what they represent. Curator: Precisely. The power lies not in historical storytelling, but in the interplay of line, form, and negative space. These elements form an analytical discourse on dressmaking. Editor: I see what you mean. Looking closely reveals layers of visual intention that reshape my perspective on art from this era. Curator: Indeed. A dedication to the elemental can often unlock a work's greatest potential.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.