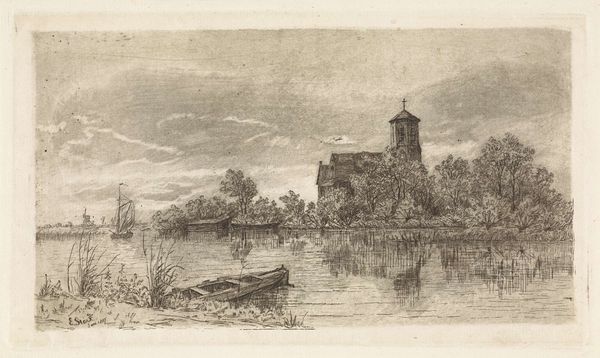

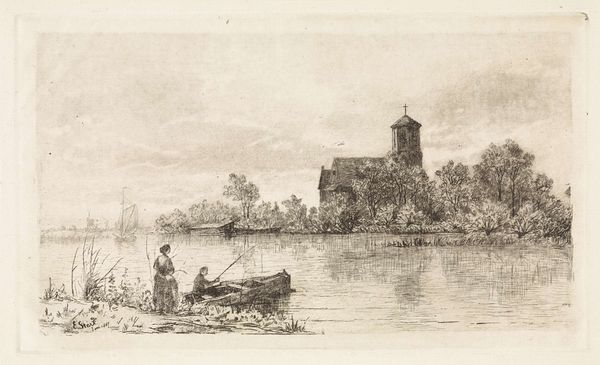

Dimensions: height 188 mm, width 240 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This print, "Toltoren te Utrecht, Romeinse tijd," made between 1865 and 1870 by Willem Steelink, presents a curious tower overlooking a river. It's quite detailed for an engraving, almost photo-realistic in some areas, yet it definitely romanticizes the scene. What historical narratives do you see emerging from this depiction? Curator: The print immediately strikes me as an interesting intersection of Romantic idealism and burgeoning Realism. While the scene seems straightforward—a landscape with figures and architectural remains—consider the title: "Roman Times." This isn't just a pretty picture; it's a commentary on Dutch identity through the lens of historical narrative and empire. Steelink's composition seems to intentionally highlight how the past is constantly being re-interpreted. How do you see that playing out in the image itself? Editor: Well, the tower, although supposedly Roman, looks rather ramshackle and overtaken by nature, doesn't it? It is placed next to a more contemporary scene of everyday life on the river, including working class families living in and beside the structure, maybe suggesting a more critical, real-world, almost post-colonial reading. Curator: Precisely. We have this idealized "Roman" past literally crumbling before the advancement of the modern world. Consider how Steelink positions the viewer – we're not invited into this grand, imagined past. Instead, we observe its remnants from a grounded, contemporary perspective, as if asking, who benefits from the creation of mythologized histories, and what stories are erased in the process? Does the print feel celebratory or cautionary? Editor: I think it leans towards cautionary, or at least questioning. The idealized past is there, but fading and in conflict with a contemporary life and a working populace trying to survive. Curator: Indeed. Steelink’s print, while appearing to be a simple landscape, sparks complex questions about how we construct identity, legitimize power structures, and engage with our colonial past. Editor: That's fascinating, I see how this romantic landscape might be viewed as a criticism of constructed history!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.