Caricature. No. 3. 2eme Pie. La noce de la fille du fermier. 1833

0:00

0:00

drawing, lithograph, print, etching, pen

#

drawing

#

water colours

#

lithograph

# print

#

etching

#

caricature

#

romanticism

#

france

#

pen

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 7 1/2 x 8 7/8 in. (19.05 x 22.54 cm) (image)

Copyright: Public Domain

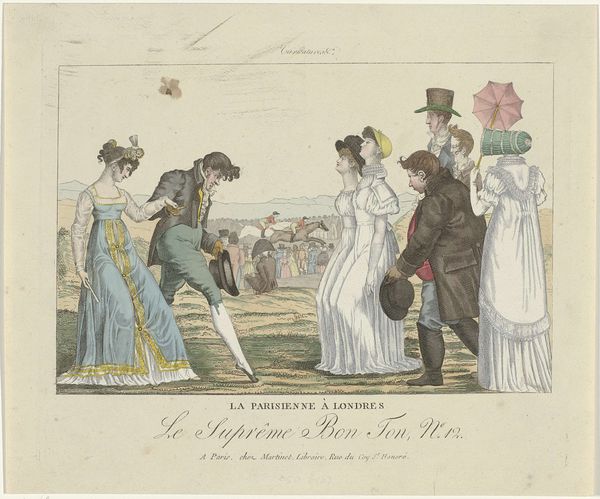

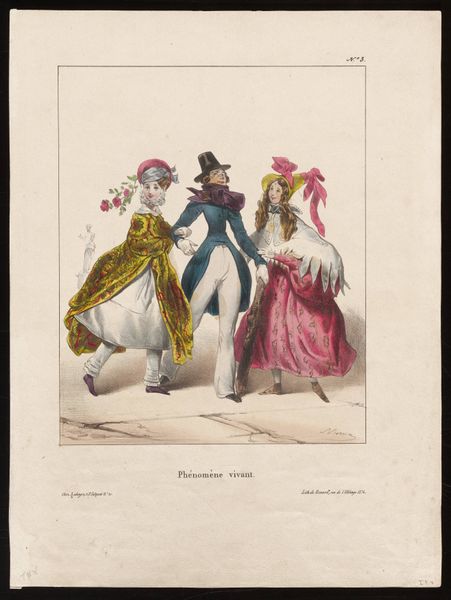

Curator: Look at this print by Eugène-Louis Lami, created in 1833. It’s titled "Caricature. No. 3. 2eme Pie. La noce de la fille du fermier"—roughly translated, “The wedding of the farmer’s daughter.” It’s a lithograph, enhanced with watercolor and pen, from a series depicting scenes of French life. Editor: Well, first impression: the composition, even with that sepia tone, feels lively. The figures are quite stylized, with almost cartoonish exaggeration. I'm drawn to how their clothing signifies social class. The details in the textile prints of their clothes, particularly the dresses, is beautiful. Curator: Absolutely. Lami, who was later known for his depictions of military life, here presents a more intimate and arguably critical view of social interactions in France during the early 19th century. Notice how he places this farmer's wedding "caricature" in contrast with the military presence— the officer, quite stiff, almost disapproving. This was during the Restoration period, so class tensions were definitely fodder for artists and satirists alike. Editor: The medium used—lithography— is crucial here too. Prints democratized artmaking in the nineteenth century because artists could rapidly produce imagery addressing class structures and the politics surrounding such hierarchies, while being more accessible than the canvases you would have seen in aristocratic households. Lami combines etching, watercolor, and pen marks with the lithographic print, to imbue more labor into his work, signifying its unique process and high value. Curator: Indeed. The clothing also strikes me as indicative of that post-Revolutionary anxiety around social mobility. Some are trying hard to imitate aristocratic fashion, others are clinging to more traditional rural attire. And it is not as idealized or polished, the Romanticism style that dominates high art, for example in paintings depicting historical narratives, so in itself already constitutes an opinion regarding the value of "history". Editor: I like your read of those clashing styles as anxiety. But I also appreciate seeing how such materials as dresses would have actually looked through textile and pattern work during that era. What I wonder about now, given this being a satire, are Lami's actual opinions regarding this display of economic disparities. Curator: That is a question that has lingered for decades. I'd say that his visual approach and medium—reproducible images that could be consumed and shared widely—suggest a certain inclination. Food for thought about the democratization of representation during times of radical societal change! Editor: I think understanding print media and the rise of democratization are key to accessing this piece’s complexities and to re-thinking its Romantic visual treatment. Thanks for discussing Lami with me!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.