#

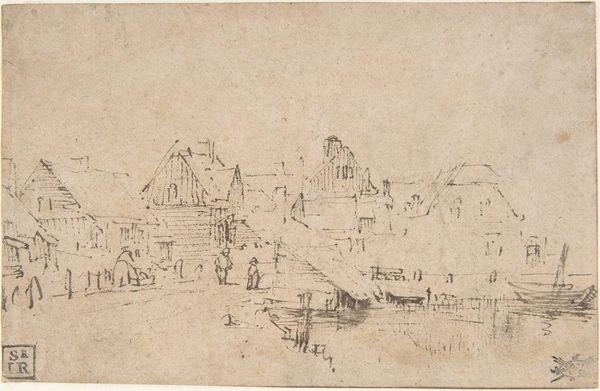

aged paper

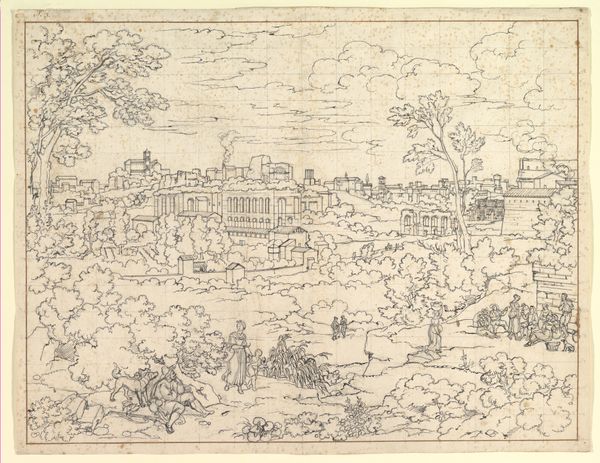

#

toned paper

#

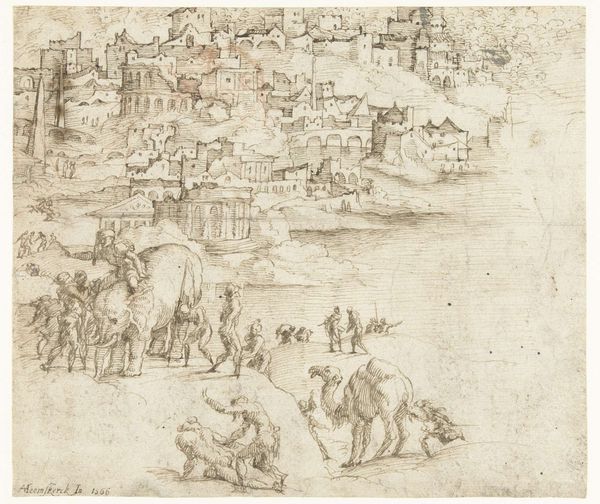

quirky sketch

#

sketch book

#

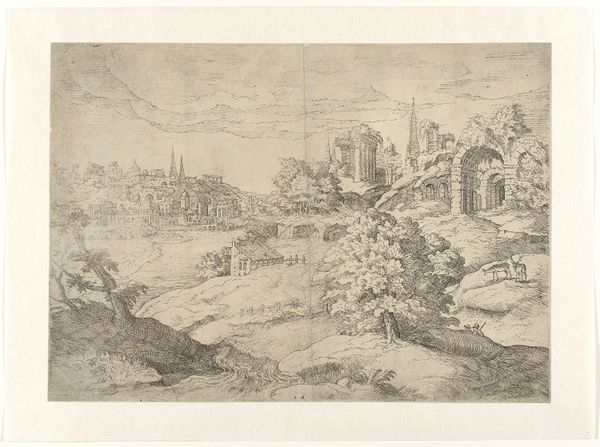

etching

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

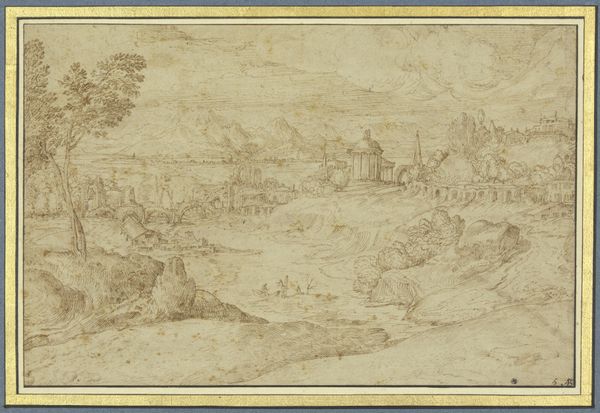

Dimensions: height 153 mm, width 225 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

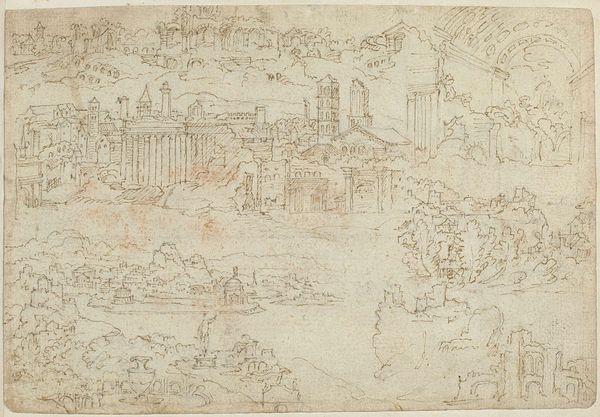

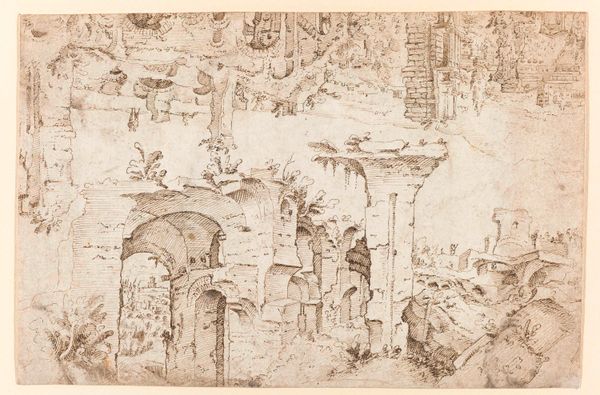

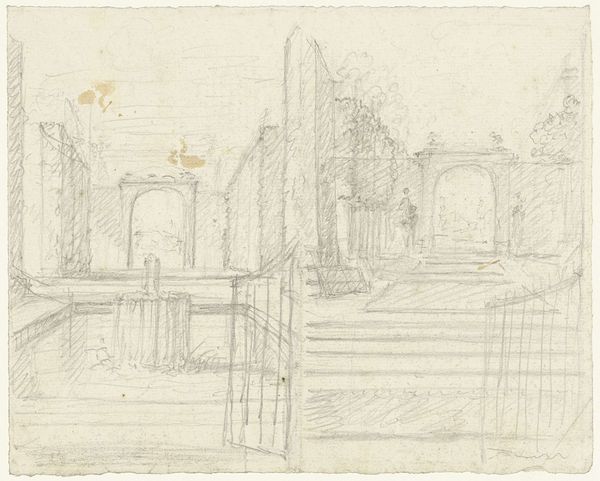

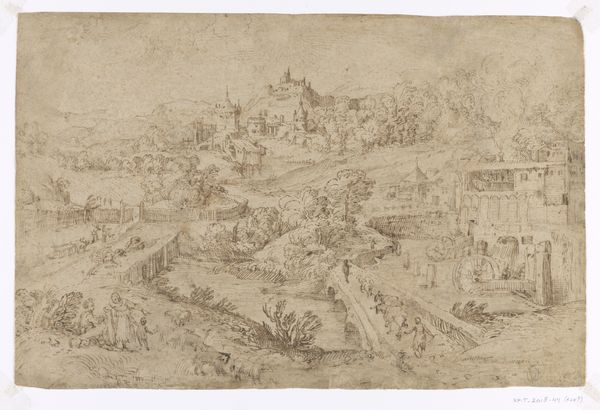

Curator: This intriguing sketch, dating from about 1550 to 1570, presents "Ruïnes en gebouwen in Rome en Antwerpen" or Ruins and Buildings in Rome and Antwerp, rendered in pen and brown ink. Editor: What strikes me is the stark contrast of architectural styles juxtaposed. A fascinatingly stark presentation! There’s an almost dreamlike quality with the structures bleeding into each other. Curator: Indeed! This blending creates an interplay, urging a contemplation on the cultural exchange, and perhaps even tension, during that period. Notice the intricate line work, typical of sketches in an artist’s personal sketchbook during the 16th century, used here. Editor: Absolutely. I find myself captivated by the sheer density of lines in some areas. The tonal variations achieved solely through line weight and density give each structure unique depth and form. How the crosshatching creates volume, yet keeps the whole piece somewhat ephemeral, is stunning. Curator: We see a confluence of Roman antiquity and early Renaissance Flemish architecture on aged paper; this emphasizes their contemporaneous existence within the artist's worldview. The cultural powerhouses of Europe united in a single composition. Editor: Do you think this represents an actual planned construction of unified styles, or merely the artists musings on differing societal values being represented side by side? Curator: Its symbolic import likely lies in presenting those dialogues about urban development and identity—particularly if intended for public projects influenced by the antique style of Rome and integrated into Antwerp. This reflects how visual imagery shapes society through design. Editor: Thinking purely formalistically though, the varying perspectives and levels of completion within a single sheet do invite us to see beyond historical representation to something about art’s method, wouldn't you say? A construction as process as much as intention? Curator: That's a crucial observation. Its unresolved nature provides room for speculative interpretation. An important example, then, of the intersection of history and subjective artistry. Editor: It allows an audience to have conversations that matter by observing an original artist do exactly the same. Curator: Precisely; now I’ll remember to always allow space in the margins of my own sketchbook, and allow others space to breathe, too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.