plein-air, watercolor

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

watercolor

#

charcoal

#

watercolor

#

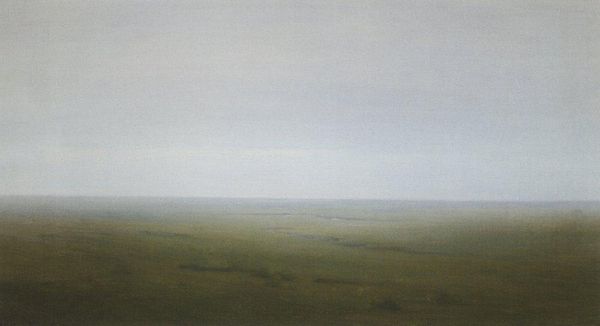

realism

Dimensions: overall: 94.5 x 122 cm (37 3/16 x 48 1/16 in.) framed: 114.9 x 142.6 x 2.5 cm (45 1/4 x 56 1/8 x 1 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: This is Andrew Wyeth's "Snow Flurries" from 1953, a watercolor and charcoal piece that really captures a sense of desolate winter. The muted tones and barren landscape give me a feeling of isolation and stark beauty. How do you interpret this work? Curator: I see this piece as deeply embedded in Wyeth’s negotiation of rural American identity. Considering the period – the post-war era, marked by anxieties around shifting social structures – how might this stark depiction of the landscape function as a commentary on the changing rural experience? Are those remnants of fences, or something else entirely? Editor: I hadn’t considered it in that light, focusing more on the literal representation of the scene. I guess they are broken down fence posts along that path. So you are thinking about it representing something about a specific moment? Curator: Exactly. It is not only landscape, it’s landscape imbued with social and historical context. Wyeth, though celebrated, has also been critiqued for romanticizing rural life, obscuring its harsher realities. This almost monochromatic palette; do you read that as honest, or as a kind of…erasure? Does the starkness highlight the absence of something? Editor: That is a challenging point. The lack of color could be interpreted as a visual metaphor for loss or decay. But that is fascinating about erasing something. The figures of people... Maybe he avoided dealing with that, but just depicted the effect of humans via fences, rather than dealing with class or racial realities. Curator: Precisely! Thinking intersectionally, how might race and class dynamics be subtly embedded – or, as you suggested, deliberately erased – within this seemingly simple landscape? And what does that absence communicate? Editor: It definitely shifts my perspective, thinking about art as being more than the visual representation but including something else. Curator: Indeed. By exploring art’s social and political dimensions, we gain a more profound understanding of both the artwork and the society that produced it. I think that I might explore the social impact of farming in 1950s Pennsylvania some more!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.