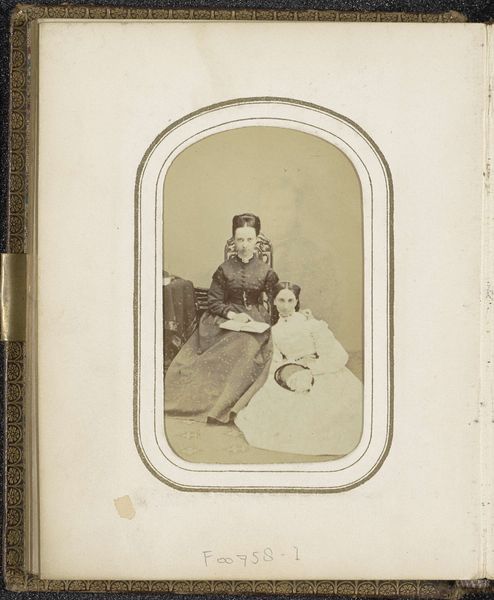

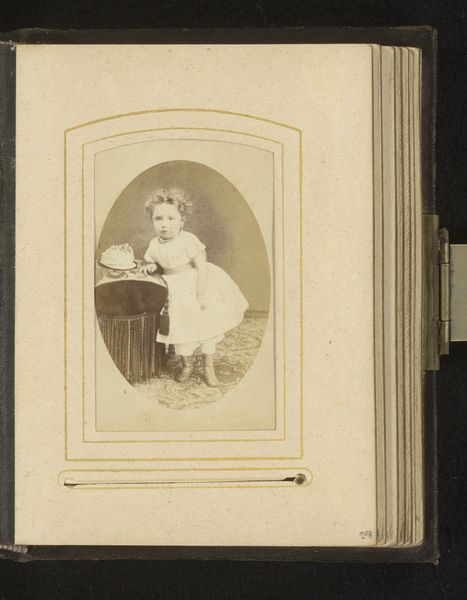

Portret van een zittend meisje met voetenbankje en een pop op een stoel 1860 - 1900

0:00

0:00

photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The photographic portrait before us, dating from 1860 to 1900, captures a seated girl alongside a doll. The image is attributed to A. Delamare & A. Raguet. Editor: My first impression is one of subdued opulence. There’s something deeply intimate, almost melancholy, in the staging, particularly considering the materials and possible techniques of early photography. It feels simultaneously familiar and distant. Curator: Absolutely. The girl's posture and expression hint at societal expectations already being imposed. And consider the doll, an icon of childhood innocence, yet here it almost seems like a prop, reflecting the role she’s expected to play. Editor: Yes, but I also see that highly patterned fabric of her dress – that required skill, labor, specific looms, global trade, perhaps even exploited labor. Photography flattens all that detail, obscures its social fingerprint while seemingly capturing it. It brings up questions about production. Curator: That's an insightful observation. The flattening does also underscore the symbols presented, such as the footstool, literally elevating her position, hinting at status. It presents the social structure in a way that speaks directly to ambition and expectations of feminine identity. Editor: I suppose the point of portraiture has always been, at its heart, economic. It serves as a record of transactions and displays social standing more than it captures authentic presence. The materials and methods always frame the subject in such a specific light. Curator: It’s a dialogue between intent and reality. Consider the carefully constructed backdrop of light and shadow—the manipulation creates an enduring image that’s ripe with multiple possible readings. Editor: These glimpses are always loaded with the labor, commerce, and material realities of their creation, a counterpoint to their ostensible subjects. We're seeing how people lived, produced, and represented themselves at the time. Curator: Indeed. By unpacking the layers, we can understand the historical memory encapsulated within it—how values, dreams, and even oppressions, become visible. Editor: Understanding both that image and those conditions provides access to deeper and wider histories.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.