fibre-art, weaving, textile

#

fibre-art

#

weaving

#

textile

#

geometric

#

textile design

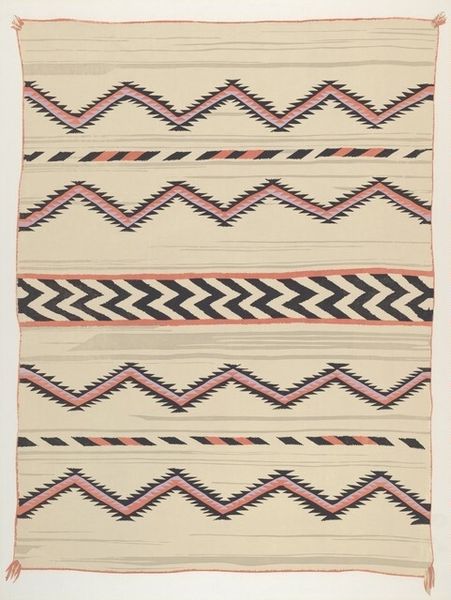

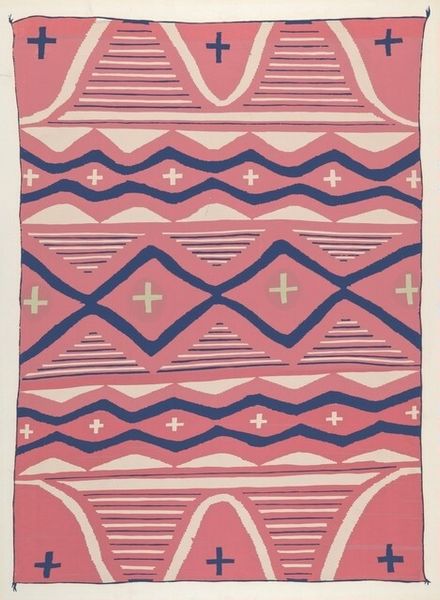

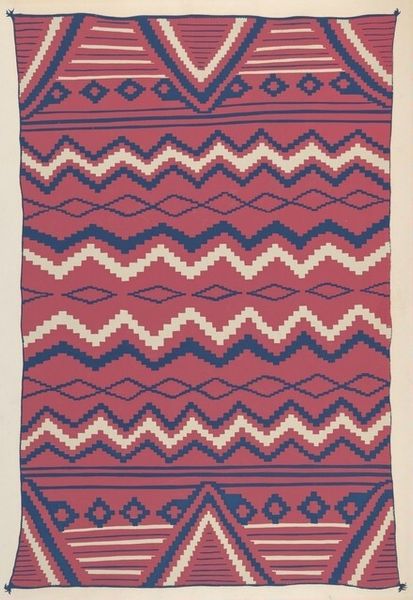

Dimensions: image: 575 x 385 mm sheet: 661 x 507 mm

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

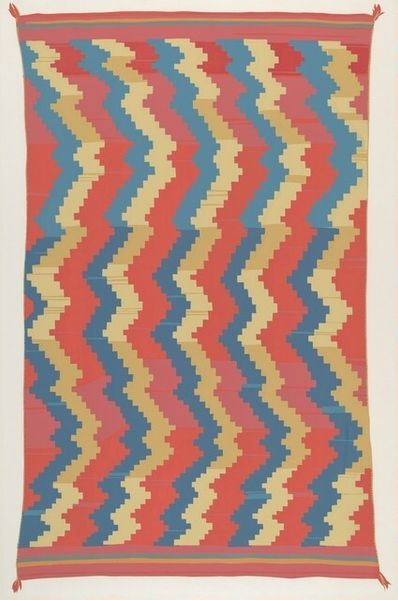

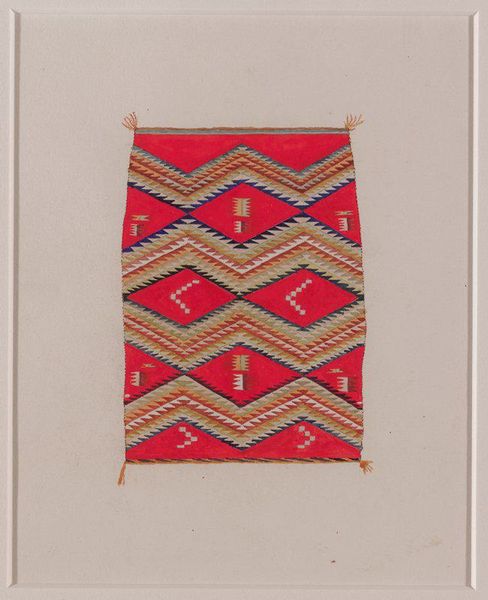

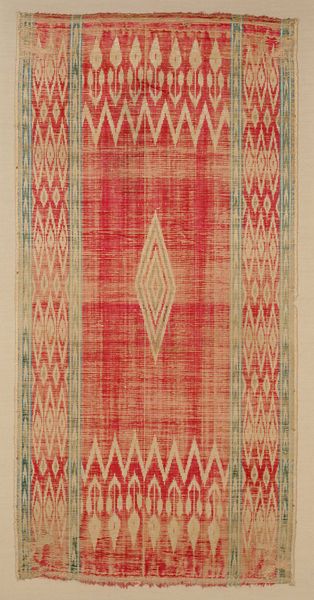

Curator: This textile piece is titled "Plate 14", created by Louie H. Ewing between 1940 and 1943. Its a beautiful example of Indigenous Americas fibre-art incorporating prints and textile design, a potent symbol of cultural expression and heritage. What’s your immediate response to this piece? Editor: Immediately, I am struck by its serenity, but also its bold confidence. The geometric pattern in pink and grey provides comfort but simultaneously directs the eye. I find it powerful. Curator: It's fascinating how cultural objects can evoke such contradictory yet equally strong responses. I see it similarly— the geometric nature is so ingrained in the tradition of its making. These weren't simply decorative motifs but conveyed complex symbolic meaning, connected to cosmology, ancestry, and societal roles. It's crucial to think about how these cultural meanings might intersect with gender roles too, since weaving practices can be traditionally gendered. Editor: Yes, considering those institutional framings brings interesting dimensions into view. How do gender dynamics in that moment shape both its creation and our modern reception of the art? Is there a record of whether this weaver engaged in the politics surrounding Native art visibility, the rise of trading posts, the evolving tourist market? Curator: Unfortunately specific biographical details can often be scant regarding Indigenous artists from this period. What’s clear, however, is the weaving itself became a critical act of cultural preservation and resistance. These objects offered indigenous people the space for expression when opportunities were frequently denied in other social and political realms. Editor: And certainly, there's power simply in the imagery, isn't there? Regardless of the intent or the maker's identity, in that socio-political time, Native American patterns themselves might have carried rebellious charge in spaces meant to confine those voices. Curator: Precisely. In understanding the tapestry's production, use, and how these relate to the socio-historical framework, we enrich our encounter and challenge dominant historical perspectives. Editor: Absolutely, it compels me to examine my own role as a viewer in this space, within this complex history. Curator: Thinking about those positions is exactly how we deepen appreciation of visual cultures, together!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.