metal, sculpture, marble

#

narrative-art

#

metal

#

sculpture

#

greek-and-roman-art

#

figuration

#

classicism

#

sculpture

#

history-painting

#

marble

Dimensions: height 224 cm, width 185 cm, depth 123 cm, weight 650 kg

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

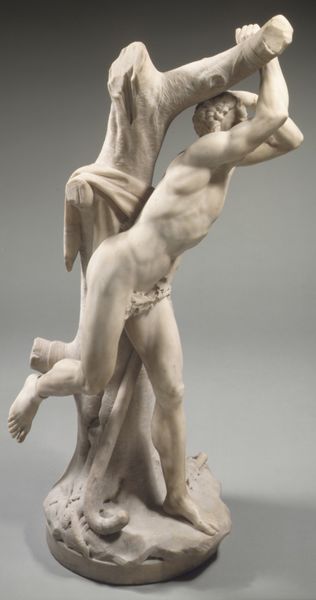

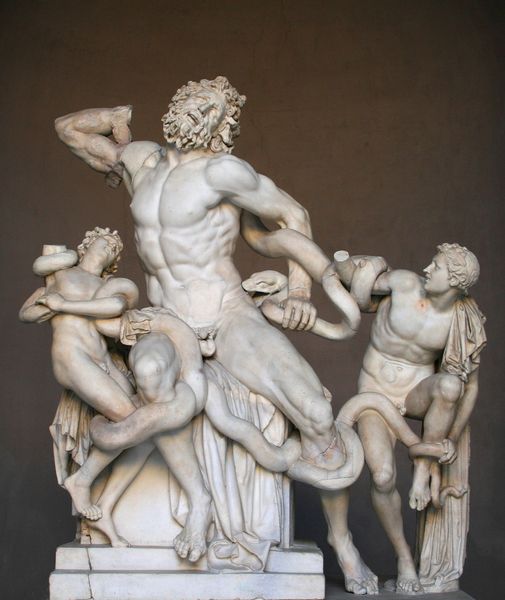

Curator: The sculpture before us, titled "Laocoön," was crafted around 1695 to 1700 by an anonymous artist working in the classical style. This version, skillfully rendered in metal, presents a harrowing scene. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: Utter chaos. Muscular bodies intertwined with writhing serpents – it’s a dance of desperation frozen in metal. There’s an almost operatic level of drama playing out. Curator: The sculpture depicts the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons as they are attacked by sea serpents. This story, drawn from Virgil’s Aeneid, carries significant weight in classical mythology and speaks to themes of divine retribution and human suffering. Editor: Retribution, yes! You feel the suffocating pressure just looking at it. But what’s fascinating is how the artist captures that struggle, making it feel… timeless. Are we meant to empathize with their suffering, or see them as a cautionary tale? Curator: That’s precisely the enduring power of the Laocoön narrative. The sculpture, though unsigned, engages with the classical ideal of depicting the human form in extreme emotional states. It evokes both pity and terror, in line with Aristotelian ideas about tragedy. Moreover, Laocoön’s struggle has come to symbolize the struggle against overwhelming forces and the futility of resistance. Editor: I see that classical rigor in the anatomy, but it’s almost violently emotional, amped up and explosive. Each figure has this unique tension, locked together in this bronze Gordian knot of anguish, yet poised, sculpted like some twisted monument. Curator: Indeed. And it reflects more than just a literal scene. It speaks to deeper cultural anxieties. Consider the symbolism of the serpents themselves - often interpreted as symbols of deceit or fate, pre-determined outcomes that humanity struggles to fight. Editor: Fate! Absolutely. We are getting a brutal look at its dance moves, too. I like that this version is in metal too. Stone captures, say, permanence. But bronze, something worked, carries the trace of process and transformation. The sense that something living can change... horribly, horribly contort! Curator: So apt. As we step away from “Laocoön," what do you feel has been illuminated in viewing this complex sculpture? Editor: That beauty can be brutal, and that some stories get sculpted again and again because they're about something elemental in us. We’re always wrestling our demons, sometimes we end up as statues frozen with serpents, locked in mortal combat. Curator: A truly affecting encounter and summation. Thank you.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

The Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons are struggling in vain against the power of two sea serpents. This group, a copy of a famous Ancient original, was cast in Rome for the wealthy Dutch merchant Nicolaas Calff. He placed the statue in the garden of his country house, Polanen, near Halfweg in North Holland.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.