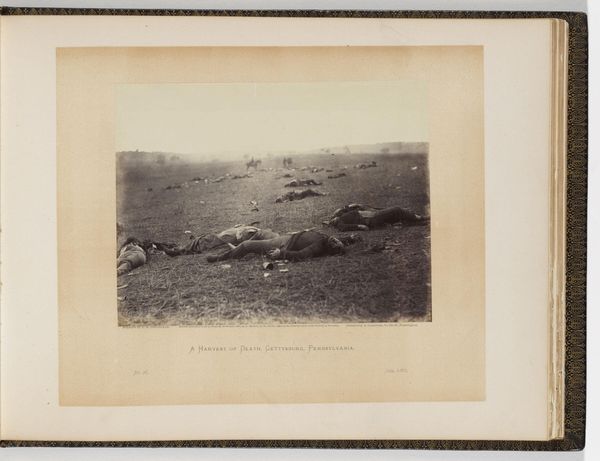

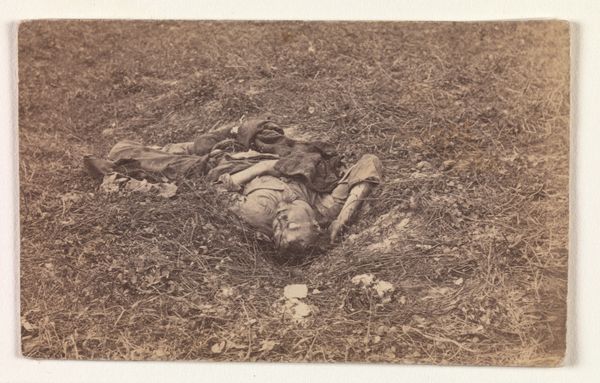

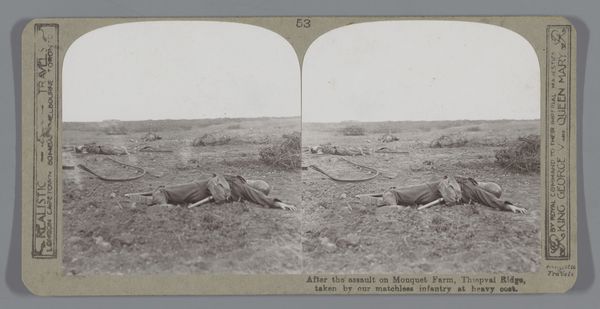

A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania 1863

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

photorealism

#

death

#

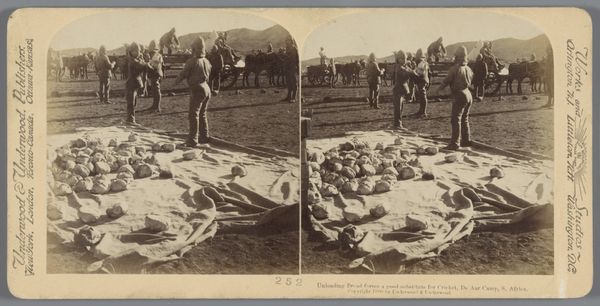

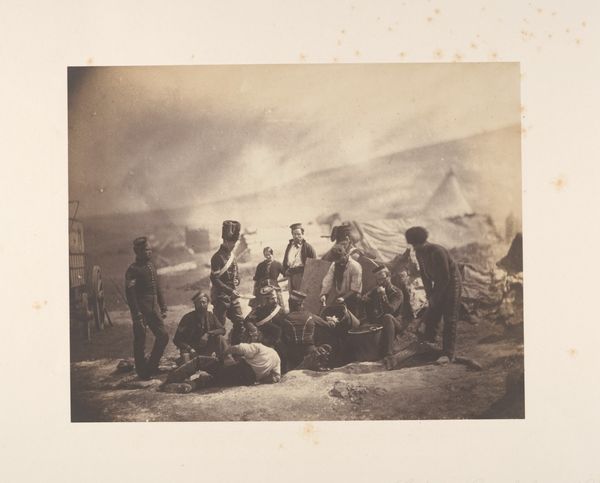

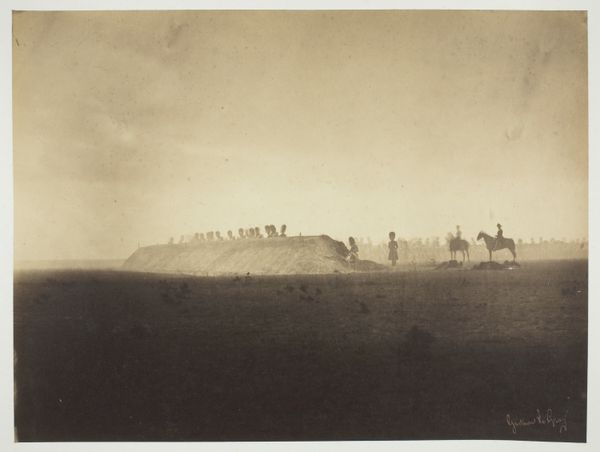

war

#

landscape

#

photography

#

soldier

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

history-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: Image: 17 13/16 × 22 1/2 in. (45.2 × 57.2 cm) Mount: 11 15/16 × 15 5/8 in. (30.4 × 39.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This gelatin-silver print is "A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania" taken in 1863 by Timothy O’Sullivan. It's a stark image. What stands out to me is the sheer number of bodies scattered across the field. What symbols or underlying meanings do you find resonate most strongly? Curator: Indeed. The bodies become symbols, not just of individual deaths, but of a broader societal fracture. This photograph acts as a mirror, reflecting a nation grappling with its own identity. Note how the photographer places us right there, in the aftermath. What feelings does that proximity evoke? Editor: It’s unsettling. I feel like I'm intruding, but also like I can’t look away. Curator: Exactly! O'Sullivan deliberately breaks from romanticized war paintings, denying viewers distance. He shows death as an indiscriminate harvest. Do you see any signs that hint at a specific allegiance or even stories for these lost individuals? Editor: Not really. They’re mostly unidentifiable, stripped bare, almost anonymous in their demise. The image denies them any individual heroic identity and exposes war’s true brutal cost. Curator: Precisely. Their anonymity invites reflection upon the universal human cost. Consider how the title, "A Harvest of Death," links the scene to agrarian cycles. This isn't just about death; it's about the reaping of a dark historical yield. Does this cyclical imagery provide some kind of cultural or psychological framework? Editor: It makes me think about the cyclical nature of violence and how quickly nature reclaims everything, including these lost soldiers. The figures will fade but the imagery remains vivid as we remember them as icons for all the lives that conflict claims. Curator: And this continues through today. So how might we use the symbolism found in the image in the future to have viewers grapple with and hopefully prevent violence and atrocity?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.