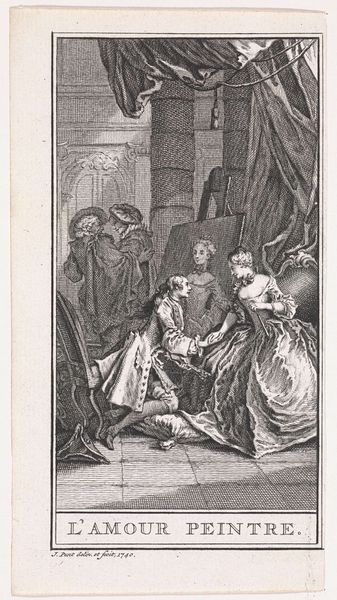

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 208 mm, width 147 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have Cornelis Boel's engraving from 1610, “Thomas Eating a Paper with ‘Ave Maria’,” housed in the Rijksmuseum. It’s striking how detailed the figures are, considering it's a print. There's almost a theatrical feel to the composition. How do you interpret this work, looking at it from your perspective? Curator: I'm particularly interested in the production and consumption aspects of this engraving. It's an object produced through labor-intensive techniques to circulate a particular devotional narrative, a fragment, let’s say, from a larger ideological apparatus. We need to consider what it meant to reproduce and disseminate this story through the relatively accessible medium of print. Editor: So, less about the specific religious meaning, and more about how that meaning was manufactured and spread? Curator: Exactly. The print medium allows for broader access than a unique painting would, engaging a wider audience in religious narratives and moral codes. Consider the labor involved, from the artist who designed it to the printer who produced numerous copies. The physical act of creating and disseminating these images contributes to a social framework around the idea that consuming such images is desirable and has real effects. Editor: It’s interesting to think about how a seemingly simple image could represent such a complex web of social forces. It gives the artwork another whole level of value beyond just aesthetics. Curator: Precisely. By emphasizing materiality and consumption, we uncover a fascinating look into the production and dissemination of both art and social ideals of the era. These objects create culture by participating in and informing our lived reality, and vice versa.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.