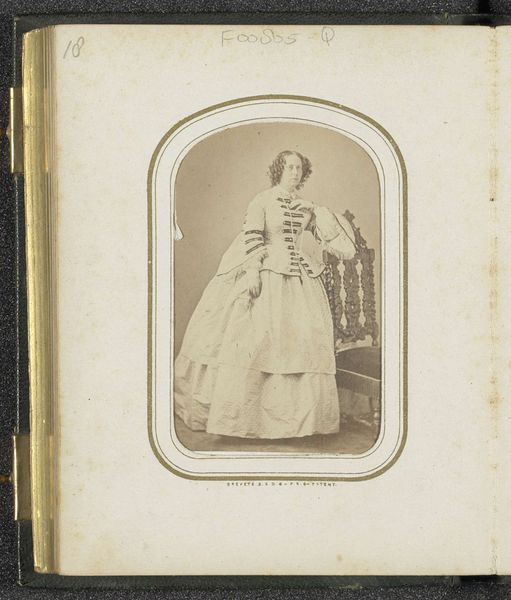

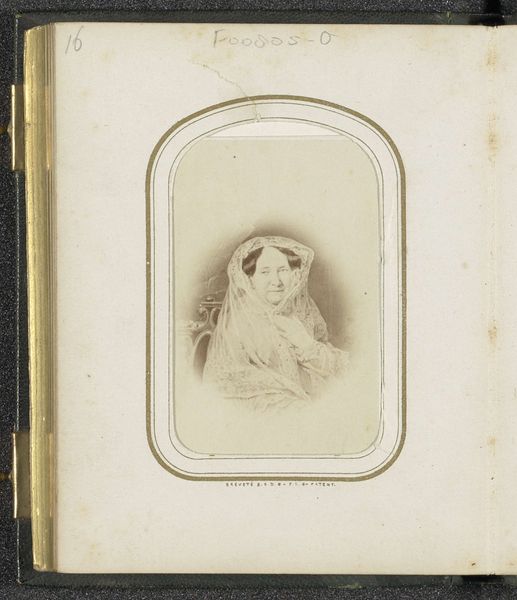

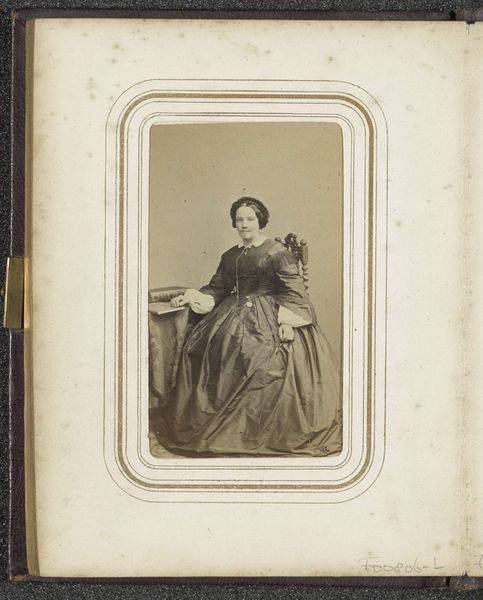

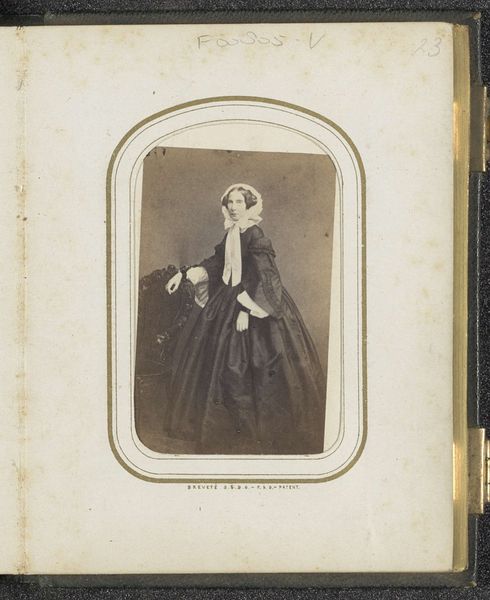

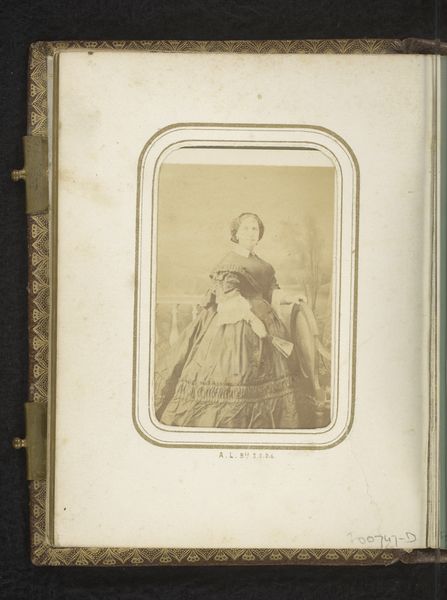

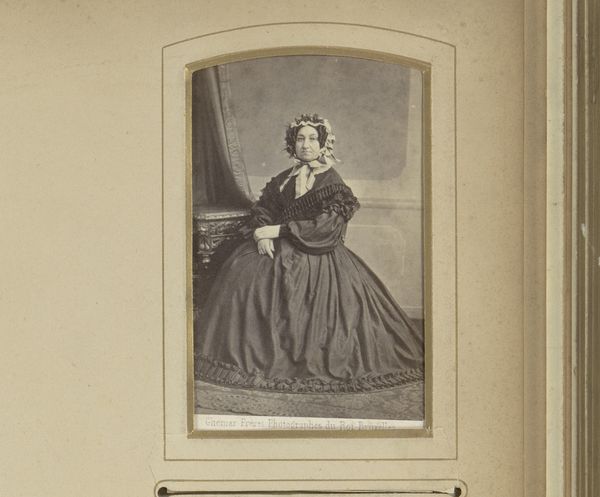

Fotoreproductie van (vermoedelijk) een prent van Wilhelmina van Pruisen, echtgenote van koning Willem I c. 1860 - 1880

0:00

0:00

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

realism

Dimensions: height 66 mm, width 53 mm, height 96 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a photographic reproduction, likely made between 1860 and 1880, of an earlier print depicting Wilhelmina of Prussia, the wife of King Willem I. It’s housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Oh, she’s magnificent! Intimidating, almost. That ruff… It's like a halo of starch. I wonder, did it feel like wearing a satellite dish? And that lace bonnet… extraordinary! Curator: The image is interesting in terms of the power dynamics at play. As a royal portrait, it clearly aimed to project authority and respectability. Wilhelmina, as queen, was a figure of considerable influence. This photograph, in its own way, solidifies and reproduces her socio-political position. Consider, too, that the piece declares its realism. But who decided what that reality would be? Editor: Good point. It feels a bit like stagecraft, doesn't it? Her gaze is very direct, very…calibrated. Yet, I'm curious about the person behind the queen. What was her relationship with power? With the burdens of representation? Curator: Exactly. And think about how the technology itself—photography—contributes to this. Photography promised a truthfulness that painting perhaps could not. But early photography was hardly neutral. Exposure times, the sitters' self-presentation, all played roles in shaping what the camera recorded. And a portrait of the queen would always involve those roles as well as status, gender, and political authority. Editor: True. Still, even through the formality, I catch a glimmer of something else. A weariness, maybe? Or is that my own projection onto a historical face? I like the sepia tones. Everything else notwithstanding, it's lovely as an art piece. Curator: Yes, these early photographic processes have a depth and richness that speak volumes to the history of image-making itself. We read her face not only for what it shows us, but also how this early technology enabled new modes of conveying not just likeness but power. Editor: Absolutely, a powerful image that speaks not only to the subject but of her time, the materials, and us as we look in.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.