metal, photography

#

portrait

#

still-life-photography

#

metal

#

photography

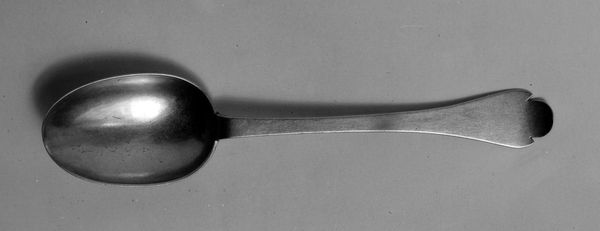

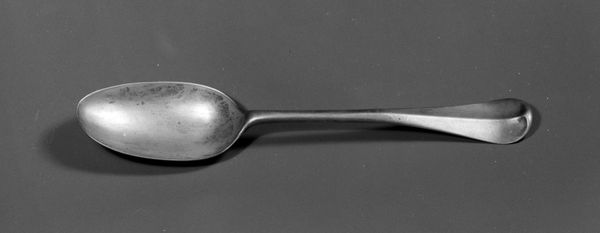

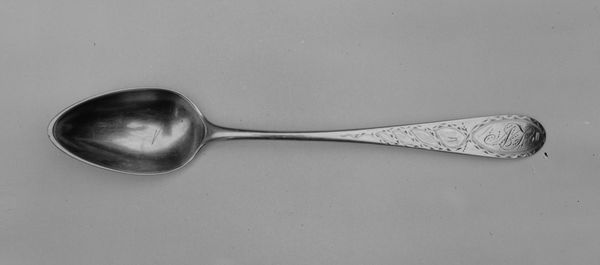

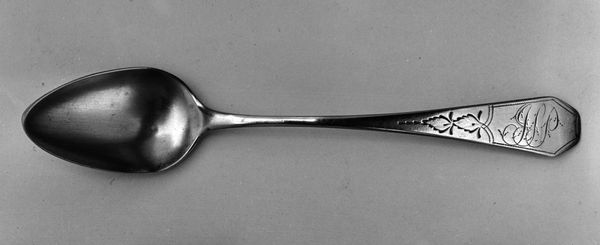

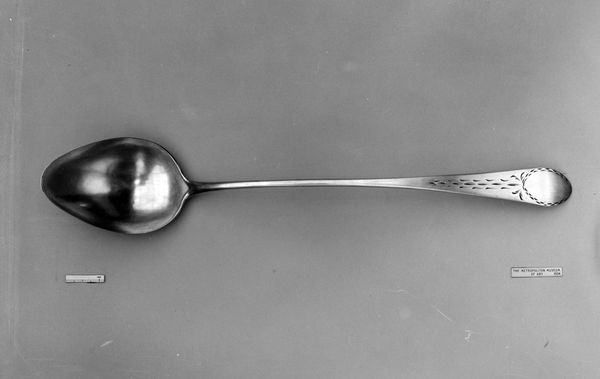

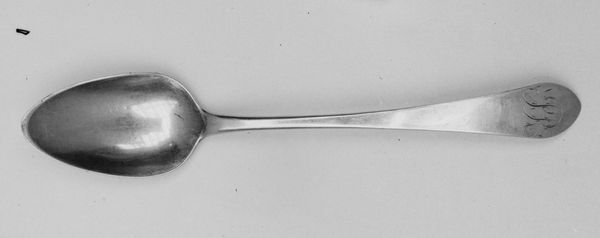

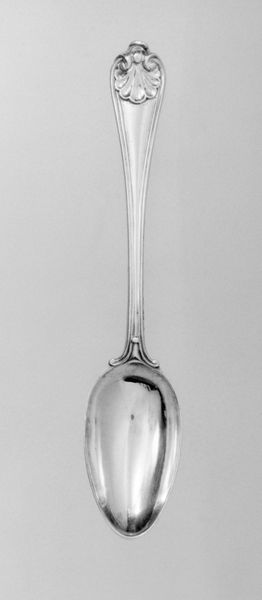

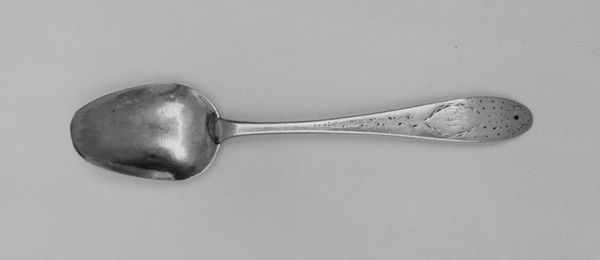

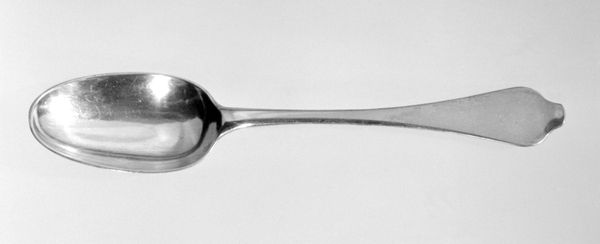

Dimensions: L. 8 in. (20.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This photograph, simply titled "Spoon," dates back to sometime between 1700 and 1800. It is currently part of the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What strikes you initially? Editor: Its starkness. There's a simplicity that transcends the mundane. I mean, it’s just a spoon, but the play of light on the metal surface elevates it. You immediately want to know the story it could tell about labor and production practices of its time. Curator: Absolutely. Consider how even an everyday object becomes art through careful selection and photographic skill. Back then, silverware was not as ubiquitous as it is today; it signified status, and more crucially access. Who used this, who polished it, who determined its place on the social stage? Editor: That's interesting because the stark composition and almost scientific detachment also remove some of that potential for romanticization, which is probably not coincidental when photographing something meant for daily life. The material – some kind of polished metal, likely silver – speaks volumes, though. We are dealing with luxury and what constitutes status. Curator: Indeed. Silverware’s accessibility wasn't equitable. Silver connects directly to colonial networks of extraction. Editor: Right. The very acquisition and shaping of that silver likely involved exploitation. What are we saying when we exhibit this now, removed from its immediate context, glossing it over? Curator: Well, by displaying and interpreting it, we provide space to critique these narratives, consider the cultural forces around design. By reflecting light, a spoon literally and metaphorically shows aspects of power, labor, and the visual culture surrounding them. Editor: Good point. Highlighting objects like these encourages reflection of our own consumptive patterns and their inherent historical linkages to power dynamics that linger to this day. Curator: It becomes more than just a utensil. It's a mirror reflecting a complex web of history. Editor: Precisely, making us question what stories such ordinary items carry, often unacknowledged, and how we as curators shape public understanding around them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.