paper

#

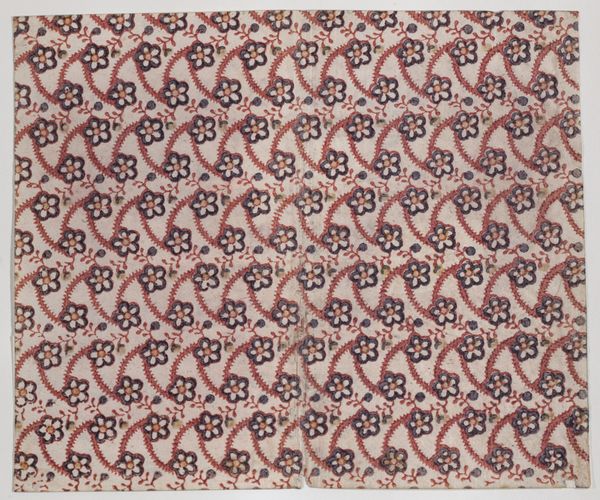

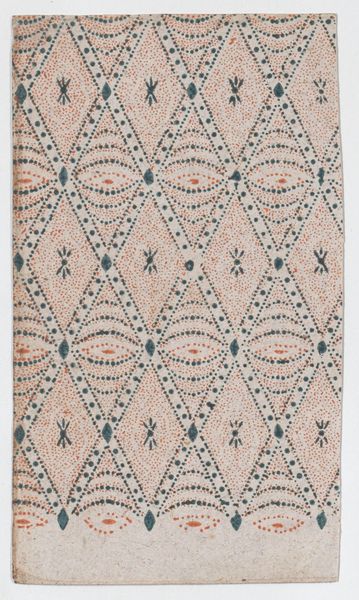

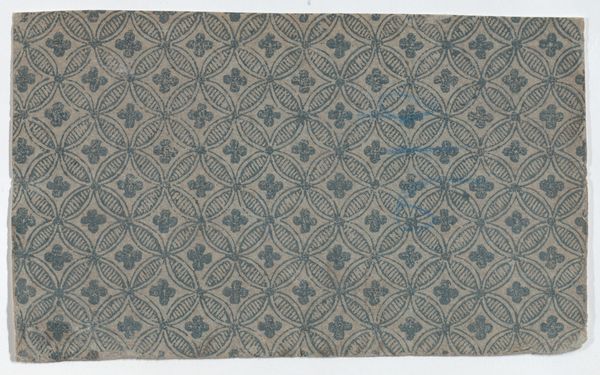

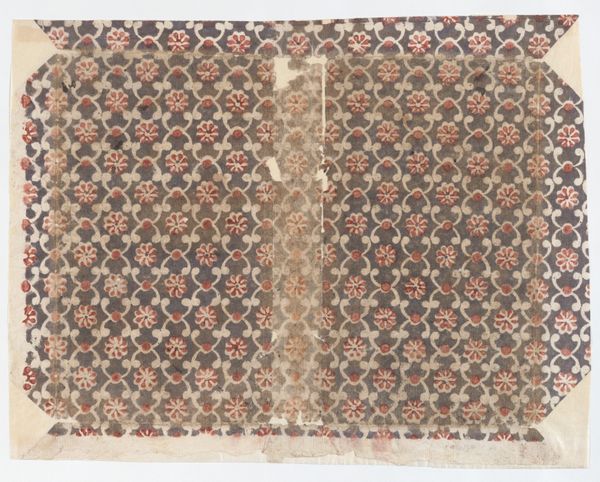

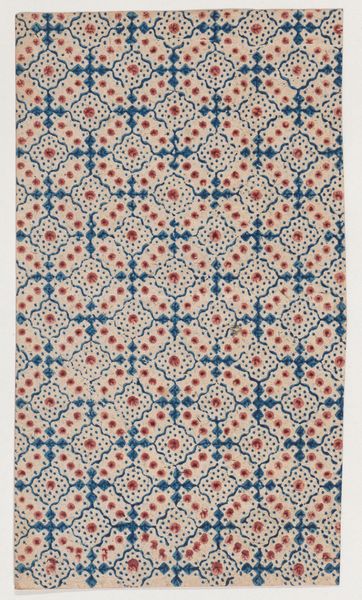

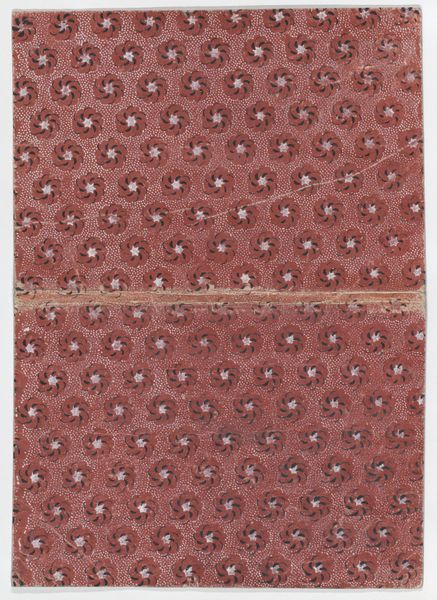

natural stone pattern

#

naturalistic pattern

#

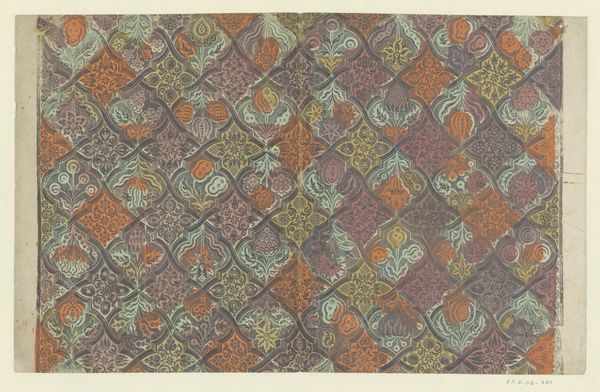

art-nouveau

#

paper

#

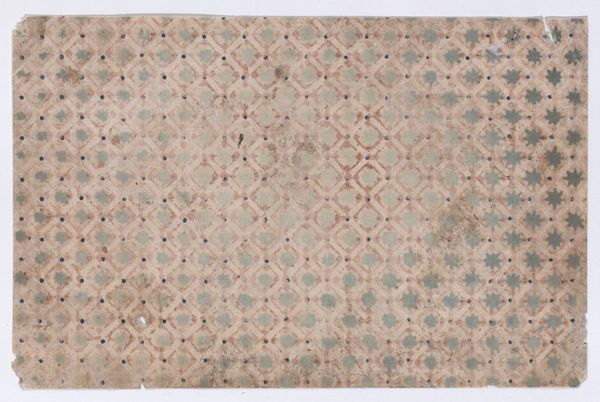

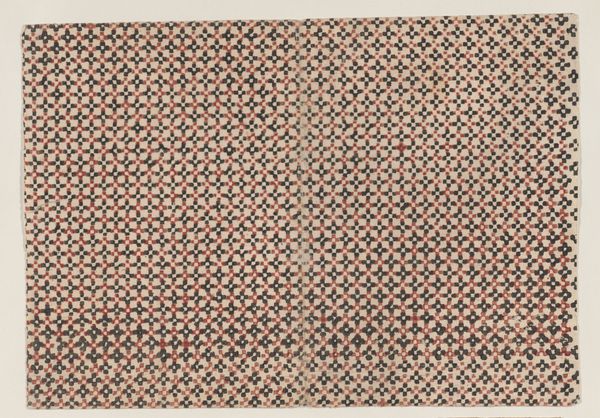

geometric pattern

#

abstract pattern

#

organic pattern

#

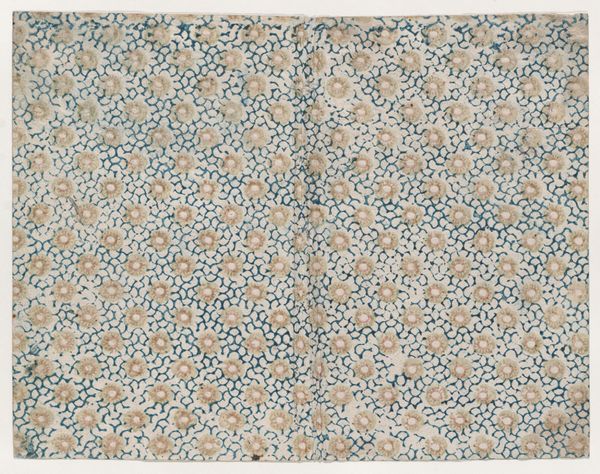

repetition of pattern

#

vertical pattern

#

pattern repetition

#

decorative-art

#

imprinted textile

#

layered pattern

Dimensions: height 1105 mm, width 840 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

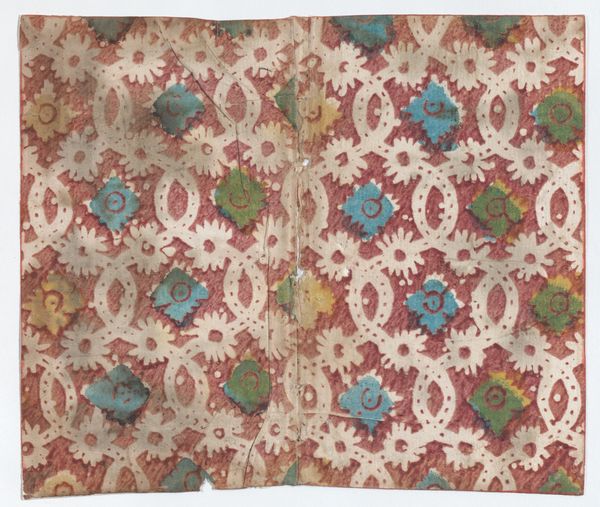

Curator: The 'Wallpaper with a Fava Bean Motif,' dating from 1898, was created by Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof and exemplifies Art Nouveau aesthetics. It’s part of the decorative arts collection at the Rijksmuseum. What is your initial take on it? Editor: The repeating patterns almost lull me into a trance. It’s quite busy, but in a soothing way. I am also wondering, what statement were people trying to make by having beans on their wall? It gives off the same soothing vibe I get from viewing botanical illustrations, but also makes me uneasy due to the very rigid patterns and shapes being imposed upon nature. Curator: It's crucial to consider the wallpaper’s sociopolitical context. At the end of the 19th century, there was a turn from industrialization and this design could be viewed as a rejection of the coldness of machinery in favor of nature, individuality, and even a pre-industrial form of craft production, which could align it with burgeoning socialist ideas around the time. The design seems to blend both. What might the repeated patterns suggest to you symbolically? Editor: Well, in many cultures, beans symbolize growth, nourishment, and even fertility. The rhythmic repetition might represent the cycles of nature, the reliable return of spring after winter, and so on. Red often stands for life force, energy, and vitality. The use of that color makes me think that Dijsselhof intended the wallpaper to bring not only nature into the domestic space, but a powerful life-affirming feeling to the domestic space, a celebration of a life lived in harmony with natural processes and seasons. Curator: I see a tension between this idyllic symbolism and the historical realities. Whose domestic space would this have adorned? Probably that of the burgeoning middle class, whose wealth was likely dependent upon industrial practices. Isn't it a curious twist, therefore, for this Art Nouveau piece to suggest a return to pre-industrial craft while existing as a manufactured product intended for private purchase? How does this disconnect strike you? Editor: A very interesting paradox to think about! It seems almost ironic. And if the wallaper existed as such, a wallpaper in an early industrial age household, then one might question whether or not it fulfilled Dijsselhof's potential artistic purpose. It feels that perhaps its symbolic function was lost as a commodity item in an ever expanding capitalistic economy. Still, you can't deny the cultural need for this piece given the context it was produced within. Curator: Absolutely, and in this tension lies its power. We’re prompted to reflect on consumerism, identity, and the commodification of nature itself. Editor: Yes, and the enduring human need to connect with nature's rhythm and symbols. This piece reminds me of what we as people really seek out within these consumeristic frameworks, no matter our social status, race, gender, and identity: nature, beauty and symbolic alignment within its rhythms.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

Dijsselhof, like his contemporary Nieuwenhuis, also designed wallpaper. The constantly recurring motifs of flowers and plants in their work betray the influence of the English decorative artist William Morris. Here six sheets have been joined together and worked up in watercolour. Dijsselhof seems to have been trying out the effect of different coloured grounds.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.