painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

oil painting

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

pre-raphaelites

#

academic-art

#

portrait art

#

fine art portrait

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

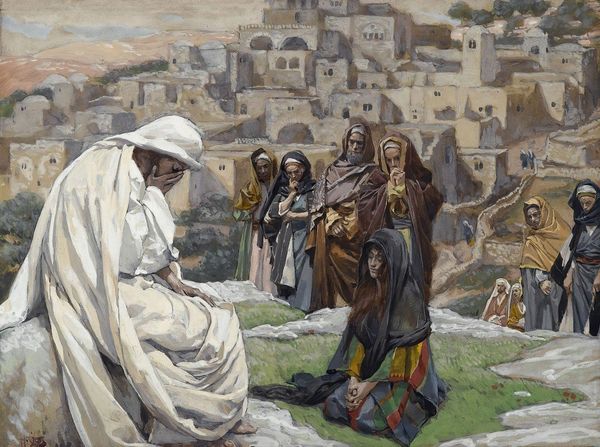

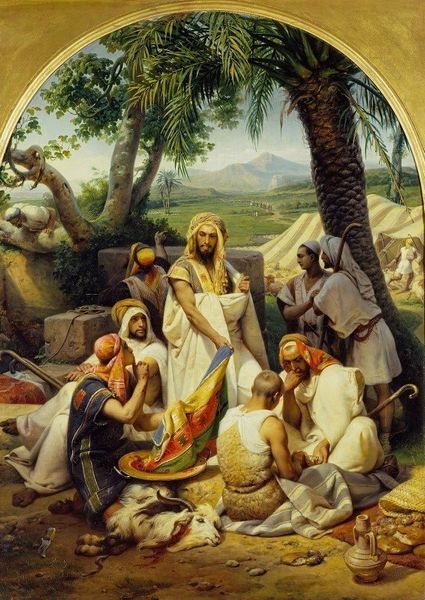

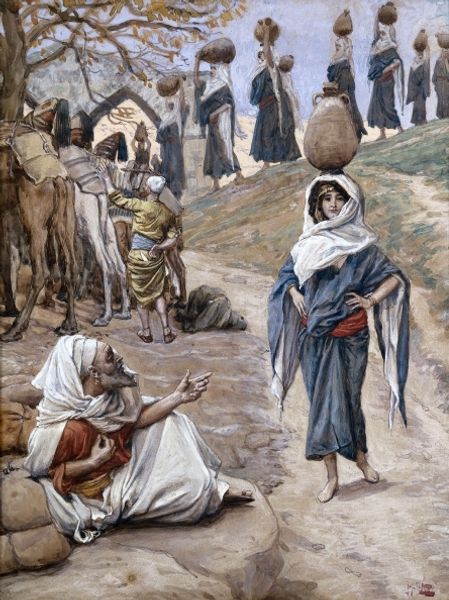

Curator: Here we have James Tissot's painting "Job and His Three Friends," created circa 1896 to 1902, part of a larger series illustrating the Old Testament. Editor: Woah. Okay, that hits hard. Visually, it’s immediately gut-wrenching – the defeated posture of Job compared to the slumped, yet almost voyeuristic stance of his companions creates this incredibly isolating composition. Curator: Indeed. Tissot was quite deliberate in choosing this moment. The Book of Job is a profound meditation on suffering, challenging simplistic notions of divine justice. Job, stripped of everything, becomes a symbol of unjust affliction. Tissot situates this within the social and religious framework of his time. The late 19th century saw a surge in biblical illustration, serving both a devotional and, arguably, a didactic purpose. Editor: I see that. The landscape, rendered with those almost dreamy washes, contrasts sharply with the figures themselves. It's as though nature itself is indifferent to Job’s suffering. I can almost feel the dryness in my throat just looking at him; it’s a tactile, deeply felt vulnerability captured in oil. It's so still, so intensely private and uncomfortable that I want to look away, but I can't. Curator: That discomfort, I think, speaks to Tissot’s success. He compels us to confront suffering head-on. However, one might critique the aesthetic choices. The Pre-Raphaelite influence, visible in the attention to detail, might romanticize or aestheticize suffering, softening the blow of Job's dire situation, potentially deflecting some of its challenging social commentary. Editor: Perhaps, but as an artist, it makes me question what beauty even means in the face of genuine despair. Is there a point where artistry can push us toward empathy, despite aestheticization? Because I still feel for him, even knowing that artistic interpretation mediates my viewing experience. The slumped postures and mournful faces—the way light catches the cloth—it draws me in and makes me consider universal themes, even beyond religious narrative. Curator: And the continuing resonance of that theme demonstrates the powerful and complex legacy of imagery depicting social and individual suffering, opening space for important conversation. Editor: Yes, absolutely. It forces the age-old confrontation with unexplainable hardships, but in colors, shadows and textures—and sometimes, that's all the push you need.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.