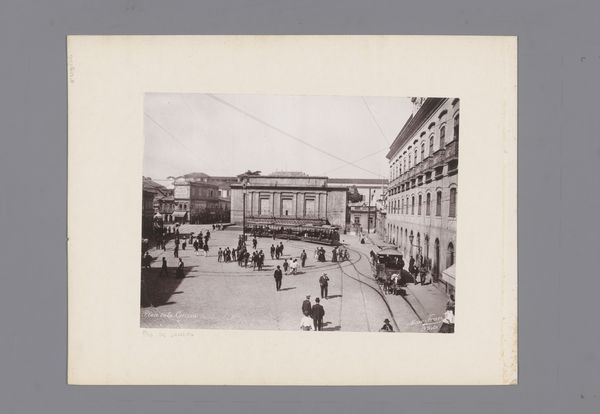

photography

#

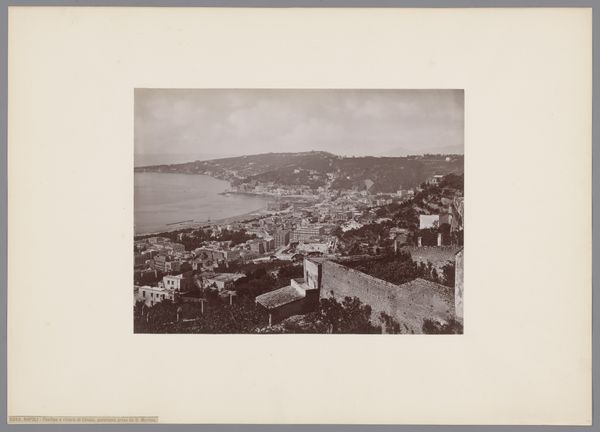

landscape

#

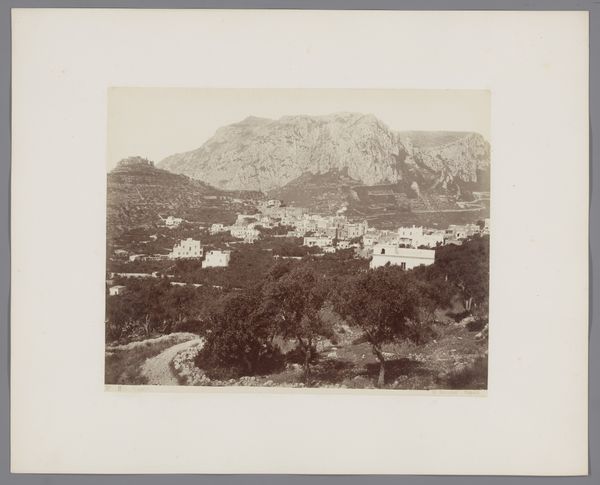

photography

#

mountain

#

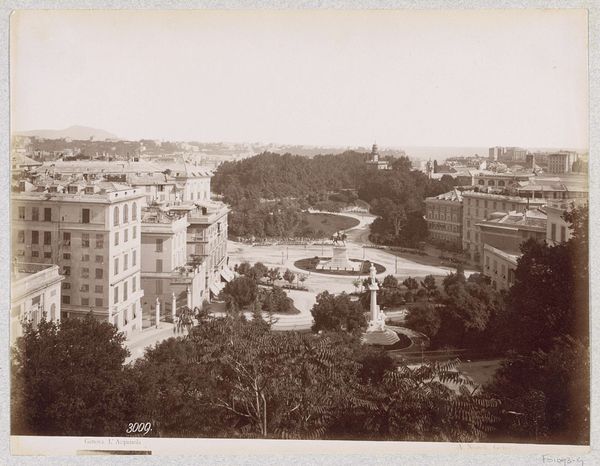

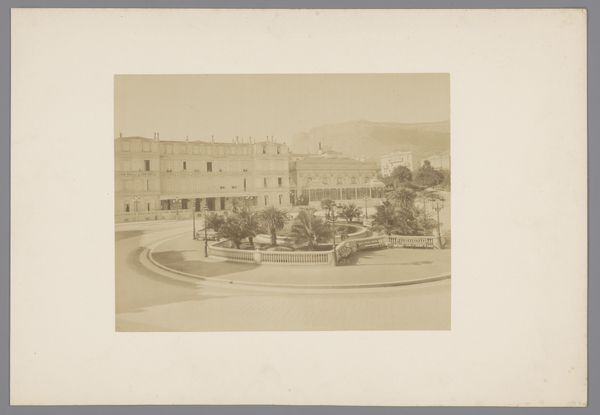

cityscape

Dimensions: height 209 mm, width 271 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Here we have a photograph entitled “Place des Alpes, Genève.” It’s attributed to Jean-Henri Jullien and thought to have been taken sometime between 1885 and 1910. Editor: My first impression is of serenity. There's a quiet formality to the scene. The subdued tonality gives the entire photograph a tranquil aura. Curator: The composition itself lends to that, I think. Look at how the architectural lines lead the eye. The geometry and tonal arrangement guide one to a certain focal range: the sky. Observe the stark difference of clouds with light filtering. Editor: Absolutely. The clouds, in turn, situate this square in relationship to much larger social forces, like climate, air quality, environmental movements...It seems almost a stage for broader struggles about place. How are we sharing the world and who has access to such beauty in an increasingly toxic climate? Curator: Fascinating perspective. Speaking more concretely, note how the artist has rendered the cityscape with a precise awareness of receding space. One observes, also, that he emphasizes formal balance—the symmetrical organization. It is clearly a well constructed work. Editor: Of course. I appreciate that symmetry but also want to call attention to how this relates to power dynamics. The architecture speaks to a time of enormous urban growth, which invariably involved dispossessing and displacing many inhabitants, reconfiguring public and private spaces based on emerging market logics. That's what these boulevards actually represent in modern memory. Curator: A perspective duly noted. Regardless of how one contextualizes it, Jullien presents us with an exceptional, if seemingly straightforward, landscape photograph. It gives a viewer an unusual glimpse into another historical world, even as its geometric strategies of ordering perception remain perpetually stimulating to interpret. Editor: Yes. It gives pause to think critically about whose stories are archived in dominant cultural records. Who decides how public squares and spaces look—then, and today?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.